The midmorning sky over the Oregon State Hospital in Salem looks liverish, quiverish, ready to collapse with torrential rain at any second. On the crewcut lawn behind the main building, an orderly shoos his excursion troupe of exercising patients back to shelter past a charter bus disgorging a troupe of Hollywood film technicians.

The two lines of shuffling men pay scare attention to each other, even when one of the patients—a spindly latino in a Hawaiian shirt—suffers some sort of convulsive seizure and slams face first to the ground. The orderly quickly kneels beside the victim, clawing for his tongue, while the other patients stand around in a frieze of distracted inattention. “Momma, momma, ayudame,” the stricken man manages to cry in a wet strangle. “Crazy,” one of the film technicians clucks, then cuts his eyes away uneasily.

A rush of wind blows a hole in the overcast. The squall begins.

A few minutes later, wearing $35 squeakless sneakers and somebody else’s awning-sized windbreaker, Jack Nicholson comes barreling down the Oregon asylum’s ground floor corridor. His gait would be arresting anywhere—a speeded-up version of the moneymaker-shaking street strut he choreographed to near-squeakless perfection in The Last Detail. Nicholson walks like Martin Balsam sounds—solid, chunky, chock full of cod-liver oil.

Strolling along the drab-linoleumed institutional corridor in the opposite direction, Michael Douglas is escorting a visiting writer through the archaic, all-too-grossly authentic mad wards where Milos Forman is directing Fantasy Films’ $3,000,000 production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Douglas is Kirk’s kid—the one who plays Inspector Steve Keller in the TV series The Streets of San Francisco. Michael Douglas is also the coproducer of Cuckoo’s Nest and right now, without all that much visible effort, he is being charming, courteous, even voluble when called upon. He has, in fact, just introduced into the conversation the pleasant fiction that he and the writer had met “years before … in San Francisco, wasn’t it?” Michael Douglas is a smooth-rising young biscuit in all respects except that he wears hideously disfigured cowboy boots the writer figures he must have copped from some dying wino in Stockton.

Without irony, the writer regards Nicholson as a national treasure. Back in the Sixties, before the bliss ninnies began slouching toward Hesse and Tolkien, McMurphy was a kind of fictive national treasure in his own right.

The writer is trying his mightiest to stay attentive, but his mind is blipping into erratic wigwags and test patterns. He has a root-canal case of the fantods. His sphincter is fluttering, he is breaking out in a sour sweat and he is wishing to hell he had an amyl or something harder to bite on.

What’s queering the writer’s internal wiring isn’t Douglas’ pleasant fiction nor Nicholson’s abrupt, looming presence—which in itself registers about a 6.5 on the Richter scale. N-o-o-o, the germ of the trouble lies in this rotten, overwhelmingly oppressive and repulsive place. At long last, lunacy—the funny farm, the loony bin, Rubber Room Inn. For years, assorted editors and ex-wives have been predicting the writer will wind up in just such a cuckoo’s nest and—well, he’s been here now for half an hour and he’s wondering queasily if he will be allowed to leave when it’s time to go. He is also wondering about his notebook. Has he mislaid it somewhere? That notebook is too goddamned important to lose—it’s an Efficiency Reporter’s Note Book No. 176, and scribbled among its 200 leaves and 400 pages are the liver and lights for two unwritten stories, plus an itemized list of business expenses totaling over $1300—God have mercy, where is that slippery fucker?

The notebook, of course, is securely glued to the viscous resin bubbling out of the writer’s swampy palm. When he discovers this, the writer executes a jerky, agitated little flamenco of relief and gratitude.

Passing abreast of Douglas and his visiting charge by now, Nicholson instantly registers the dysfunction. The actor flashes Douglas a high-caloric high sign in greeting, then swivels his gaze to zero in on the writer’s sagging knee action. Unsmiling but not unsympathetic, he notices the man’s small, panicky dance of distress and release, the jittering after-shock of wrenching visceral trauma. He files it all away for future reference. Nicholson notices things like that and no doubt uses them to flesh out his riveting film performances.

Without irony, the writer regards Nicholson as a national treasure. This literalist view of the actor will get in the way of the substantive story waiting to be perceived here, but not for long. Meanwhile, Nicholson whips past in his squeakless sneakers, vanishing soundlessly down the institutional corridor.

With the writer in tow, Douglas advances a kilometer or so into the bowels of the fortresslike asylum, pulling up short at a point in the corridor where the color of the walls abruptly changes from scabrous green to shit brindle. In his voluble register, Douglas is explaining—no, proving—that this is no gypo movie of the week they’re engaged in here; nosirreebob, this is the quality goods, an AAA feature of the caliber that’s rarely indulged in anymore for all your ersatz disaster operas and Godfather begats. Standing near the wire-mesh entrance to ward four, the film’s principal set, Douglas ticks off Cuckoo’s championship qualities on his pale, pencil-thin fingers:

“Our daily nut is $35,000, see, so with that kind of dough at stake, we’re not chintzing around about anything. When Saul and I decided to do the picture”—Saul Zaentz is the Main Man at Fantasy Records/Films in Berkeley and Cuckoo’s other producer—“we agreed first off that we’d only settle for the best. I mean, screw it, across the board, whatever the field of talent, whatever the cost. And we got it all, man—everybody and everything we wanted—bam, bam, bam! Nicholson was our first and only choice for McMurphy. Nicholson is the ‘bull goose loony’—watch his stuff this afternoon and you’ll understand what I mean.”

Nicholson as McMurphy—a dead-solid ringer. Back in the Sixties, before the bliss ninnies began slouching toward Hesse and Tolkien, McMurphy was a kind of fictive national treasure in his own right. Everybody—everybody who could read, anyway—copped a hint of style and character from the hell-raising drifter who feigned insanity to escape a penal farm, who locked horns in the mental slammer with the tyrannical Big Nurse, who both won and lost the battle and in between gave life-to-life resuscitation to the Chronics and Acutes on his ward.

“And Milos,” Douglas goes on, “he’s just goddamn marvelous—one of the finest directors in the world. It’s a wild thing to watch happen. We’ve got a great cast, down to the tiniest walk-on, and probably the best crew in the business. Jack Nitzsche is composing the score … Bill Butler’s our cinematographer—he just did Jaws. And, lessee—oh, yeah, the sound man, Larry Jost? He’s up for an Oscar for Chinatown—just like Jack. But, come on, let’s go take a run around the set. Brace yourself, though. I warn you, man, it’s terrible—it’s ghastly.”

Yes, exactly. Ward four would gag a maggot. It is a cagelike enclosure furnished in the brutal paraphernalia of shrink-tank pathology run absolutely amuck: cramped rows of hospital cots with rumpled gray sheets and matted blankets … obscenely stained bed tables littered with puke pans and hot-water bottles … a scattered fleet of decrepit, cane-backed wheelchairs … framed calendar portraits of dogs and wild geese hung uniformly awry … and perched above all this mess, on a high, centrally located shelf, a smeary-windowed TV set bearing the brand name of its manufacturer, one “Madman” Muntz.

An immaculate, glassed-in nurses’ station controlling egress to the ward cage rounds out the picture. Big Nurse’s Orders of the Day are posted there on slot cards in a wallboard. The slot cards read:

THE YEAR IS 1963

TODAY IS WEDNESDAY

THE DATE IS DECEMBER 11

THE NEXT HOLIDAY

CHRISTMAS

THE NEXT MEAL IS BREAKFAST

THE WEATHER IS CLOUDY

Ye gods, The Compleat Toilet—“OI’ Mother Ratched’s Therapeutic Nursery,” in Kesey’s phrase. Which prompts the writer to clutch his sweat-slick notebook all the tighter and wonder aloud about Kesey’s connection with the film.

Douglas takes on the expression of a man who’s just been put on hold during a transoceanic call. He motions vaguely toward the ward’s rain-blurred windows. “I can’t say for sure,” he mutters, “but I’ve heard he’s out there in the hills somewhere muttering rip-off. We hired him—paid him over $10,000—to write a first-draft screenplay. We found out pretty quick that he couldn’t write screenplays to suit our standards, and he couldn’t get along with the people involved, and he couldn’t or wouldn’t show up for production meetings. From what I hear, he’s been spreading the word that the movie version distorts his book. Well, fuck it—I just have to disagree, that’s all. We’ve taken some liberties with the basic material, sure, but all of us expect the picture will come very close to the spirit, the wallop of the book. Milos thinks it will, and Nicholson thinks so, too, and so, in fact, do I.”

Douglas dismisses the subject with a short shrug and points along the corridor, grinning. “See that place where the color of the walls changes? That’s Milos for you—a stickler to the teeth. He made us repaint the whole ward—dirty beige, I guess you’d call it. I asked him, ‘Why, Milos?’ And he said, ‘Vy? Because ve cahn’t chute an entire comedy against green, dot’s vy.’”

By this time, members of the technical crew have started work around the nurses’ station, hammering and sawing and wheeling around bulky film equipment on dollies. Wandering among the electricians and gaffers and grips are a dozen or so other men—odd-looking spooks dressed in ratty old hospital robes and felt slippers. These, presumably, are some of the actors who portray Kesey’s Chronics and Acutes. Uh-huh … and where, uh, are the real patients, the certified dafts?

“Everywhere,” Douglas crows with a gleeful sweep of his arms. “Well, no … let me qualify that. The patients committed here are quartered on the third floor. Oregon, you understand, like a lot of other states, is releasing a high percentage of its mental patients to so-called local responsibility.

“But, see, the director of this hospital—a terrific guy named Dean Brooks—has very advanced and, I believe, civilized ideas about what constitutes good therapy, and the distance from the third to the first floor is just two flights of stairs. In other words, there’s an amazing crossover between the film troupe and the patients. Everybody visits back and forth, plays pool, plays cards, horses around together. A couple or three of the patients are even working for us in various small jobs—and you can actually see the effect on their spirit, their morale. After a while, they start to blend in and—hell, at times there’s no way to tell the patients from the crew. Look over there—see the little fellow with the broom? He’s on the payroll—Ronnie the Patient—interesting guy, as I’m sure you’ll discover. Two months ago, Ronnie was classified as a catatonic mute.”

Douglas indicates a frail, stoop-shouldered boy-man, perhaps 25, who is abstractedly sweeping sawdust into a pile near the entrance to the nurses’ station. He is wearing vague, Permaprest civvies and a vague, Permaprest smile that disappears into a brush mustache and no chin at all. He is clearly crazy at a glance, but just as clearly harmless.

The writer stares toward the nurses’ station, scanning the individual faces of the workers and actors congregated there. Sure, he nods numbly. Crazy.

The lingering insane of Oregon—some of them the criminally insane—are upstairs on the third floor. Well, except for the ones fraternizing down here on the first floor. The writer considers this awhile and searches out a hidey-hole where he can repair unobserved. There, in crying need of repair himself, he hikes up his coattails and jams his Efficiency Reporter’s Note Book No. 176 deep into the rear waistband of his trousers, snug between belt and bum. The writer feels immensely better for this, although he has somehow lost track of his Sony TC-126 tape recorder.

The hospital’s Tub Room looks like a used-bathtub lot washed up the coast from the psychic environs of L.A.’s Pico and Western. A few minutes before noon, Forman is in there having a heart-to-heart with Scatman Crothers and Louisa Moritz. The two are about to play a seduction scene involving a drunken ward attendant and a fragged-out semipro whore. Roughly three dozen technicians and onlookers are shoe-boxed into the sweltering, seedy-tiled hydrotherapy facility where Oregon’s crazies used to assemble faithfully for the purpose of undergoing water torture. The writer is huddled spine down in one of the enamel-peeling tubs, keeping an eye on as much of the elbow-to-ass action as he can follow. “Quiet, please—let’s get it very quiet in here,” one of the assistant directors bawls.

Forman concludes his huddle with Crothers and Ms. Moritz, nods curtly and strides off a few paces to fire up his pipe. A human path peels open for him wherever he chances to move. The Czech-born director is hairy on the head, arms and chest and built like a lunch box wrapped in a pair of old San Pedro-style dungarees. He is prone to yelling a lot when he gets excited.

For one take, Scatman improvises the line, “Let’s get drunk and be somebody.” For the next take, he rephrases it. “Let’s get drunk and be somebody else.”

Louisa Moritz, with the face of a zonked china doll, scratches a lank flank through her grungy pedal pushers and puts on what could be interpreted as a pensive look. In a glissando croak, she allows to Scatman that she doesn’t much care for one of her lines. “Say anything you want to, honey,” he urges, patting her hand comfortingly. “Don’t worry about it, you hear what I’m tellin’ you? Fuck it.” “Oh, I know!” Louisa crows in inspiration. “I’ll say—at the end?—I’ll say, ‘Oh, well, what the hell—any old fart in a storm.’ Isn’t that better?” Scatman cackles and claps his hands on his slick black pate in delight: “Yeah, yeah, crazy, that’s fine, that’s awright! Listen, I tell you what, girl—why’n’t we just wing it? Hell, let’s have us some fun! Shoo-be-dop! Jabba-dee-boom! Skee-doop! Zack!” Louisa giggles into her fingers and crosses to her toe mark.

“Everybody quiet!” another assistant thunders. Forman raises and lowers a hand in the hanging silence. “Roll, please,” Bill Butler murmurs to his camera operators. Two grips with slapsticks spring before the massive Panavision cameras. “A and V 107, take one, A camera.” “B camera.”

The cameras begin to whir with a faint ta-pocketa-pocketa, and the scene flows like water. Scatman, playing an orderly named Turkle, entices Louisa, a dim-witted mattressback, into a deserted corner of the Tub Room, where he plies her for a taste of strange with Smirnoff, Tokay, and generous doses of speedy sweet talk. She responds by covering her head with a brown paper bag—that’s her impression of a fish—and prattling off a long, disjointed story about a dead boyfriend who got that way by gobbling light bulbs. During this synapse-rattling recitative, Turkle is steadily stroking his way up her pedal pushers, but just as he is about to lay hands on her trade goods, a prearranged KAW-BLONG! off-camera propels him to his feet in petrified consternation. What the fuck—those goddamn Chronics and Acutes—they’re stain’ a midnight insurrection out yonder in ward four! Holy fuckin’ doomsday—Big Nurse will mess her whites!

Scatman and Louisa play the scene five times, five different ways. They play it fast and slow, sweet and sour, mournful and manic. They play it fey and lyric—every way but poorly or backward. For one take, Scatman improvises the line, “Let’s get drunk and be somebody.” For the next take, he rephrases it. “Let’s get drunk and be somebody else.” Louisa fields all of Scatman’s wild tumeling and burns back a few swifties of her own. The two are natural foils, the Lunt and Fontanne of bull goose loonydom.

Forman watches the good times roll with tooth-sucking detachment. His response to all but the final take is unvarying: “Cut, cut, cut, cut. Very good, very perfect. Ve vill chute it again, please.”

As the crew begins to strike the set, Scatman and Louisa wink, embrace and take their leave of Bathtub City. Entranced, the writer flexes out of his porcelain squat and trails them to a makeshift dressing room furnished in rump-sprung rattan. Plopped down beside Louisa on a litter-strewn settee, Scatman airily waves the writer toward a chair positioned beneath a Lenny Bruce poster. “Set down, friend,” Scatman croons, “you look like you come from about halfway decent stock.”

Scatman produces a tenor guitar from somewhere, an age-burnished Martin, and begins whanging hell out of its four strings: “‘Who’s sorry now /Who’s sorry now.’… Jabba-dee-wop! Dee-onk, dee-onk! Ain’t that tasty, though? Listen, you ever watch Chico and the Man? I’m Louie the garbage man on that mutha—I’m the man who empties your can! Can you dig it? ’Cause never forget, you are what you throw out!”

Louisa has a guitar, too, a Japanese job, and she starts singing something that goes “Da-da-da-dee-da-da.” The effect is singular—comparable, maybe, to the death rattle of a squeegee. Scatman tries his best to harmonize with her. “Ain’t she pretty?” he beams. “I love this lady—I’m crazy’bout her. She’s the real Divine Miss M!”

Louisa segues into “Behind Closed Doors,” but she hits a clinker that makes her stamp her foot and hiss, “Oh, for the luvva shit!” She winks conspiratorially at the writer and asks, “Did you see our little scene just now? … Oh, I’m so glad. It was supposed to make you laugh. Did you see my Alka-Seltzer commercial last night? It was supposed to make you buy Alka-Seltzer. … I do a lot of commercials, uh-huh, but I also do the Carson show, and I’m doing more movie roles lately. Some pulp men’s magazine ran a story on me last month, but they didn’t get my credits right for the last four years. Truly. I just did the second lead in a picture with David Carradine called Death Race 2000, and they didn’t even mention it. I mean, you would think people would do their jobs or something.”

“There’s a man does his job—the head nigger of this joint!” Scatman cries, racing to the door and tugging Dean Brooks into the room by a tweed sleeve. An affable, gracefully graying man, the director of the hospital shakes hands all around and murmurs something sympathetic about Louisa’s chord-strumming ability. “Oh, well, thank you,” she chirrups, “I only started playing, lessee, oh, about three hours ago.” “Dr. Brooks here is one helluvadoctor,” Scatman assures the writer, “one helluva shrink. And you know what? He plays that same part in the movie—a shrink. Ain’t that weird? Wobba-dee-doo-bop! Pa-hoochas-matoo-chas! Merf!” “I’ve got one more scene to go,” Brooks mock sighs, “but right now I’m on my way back up to the third floor, where it’s safe.”

Scatman follows the doctor away, seeking, as he says in a braying aside, “free medical advice—all I can get. Hell, babies, I’m sixty-four.” Louisa waves toodle-oo to the two and commits murder one on the intro to “Sounds of Silence.” She snuffs the rest of the song, too, chord by chord, line by line. “Isn’t that pretty?” she asks at the end. She laughs at the writer’s poleaxed expression and pokes a good-natured finger at his midsection: “Don’t forget to put it in about Death Race 2000.”

The commissary is another recycled mad ward where the Cuckoo troupe assembles en masse at four P.M. daily to be served up mess (yes) by a local catering outfit. In the early afternoon, the place is virtually deserted. Saul Zaentz, the picture’s coproducer, is in there noshing a fast bear claw. … The brawny kid with the purple birthmark who tends to the coffee urn is tending to the coffee urn. … An actor named Danny DeVito is escorting his kinky-haired ladyfriend fresh from da Bronx on a tour of the dingy dining area. Kind of a neat-o place, once you get the drag of it. Tablecloths. Funny pictures and shtick on the walls. Almost like the old Village, sort of….The lady has the drag of the place at a glance and she is rolling her eyes in speechless revulsion. She is scanning all visible surfaces for—who knows?—cockroaches, spirochetes….God, and she flew all the way across the country to break bread in this Dachau of the stomach?

The writer enters the mess hall in search of anything wet and he tunes in a sound. Rrr, rrr. Low but distinct, the sound reminds him of—he can’t immediately think what. Zaentz strolls across the tatty linoleum and pokes out a family-sized paw in greeting. “Good to see you again,” the shmoo-shaped producer says with a benign show of teeth. “We met years ago, if I’m not mistaken—in Berkeley, wasn’t it?”

That pleasant fiction again. The writer puzzles over it briefly, but it doesn’t yield up much of a mystery. In plain-vanilla usage, it’s a mode of status shorthand that is commonplace among film folk. It’s Gollywood’s way of saying: I’m OK—you’re OK. If you’re here among the Somebodies, then you must be a Somebody, too. But I already know all the Somebodies, so we must have met somewhere before … Sure, we met before … Berkeley … Barcelona … some fucking place….

Rrr, rrr—that sound again—sinister.

“Been a lot of yelling around the set recently,” Zaentz muses as he munches the heel of his bear claw, “but that’s par for the course, a deal like this. I mean, this has been a goddamn long location. We got here the first week in January and we’re halfway into what now—March? That’s ten weeks—lots of long hours, tough setups. And we’ve got two, three more weeks to go, so naturally everybody’s getting a little—edgy … you know how it goes. Hell, I’m a little edgy myself. But in my estimation, it’s all been worth it. We’ve put together one classy picture—everybody connected swears it’s a killer. Who’d stoop to shitting about a thing like that?”

“Lemme tell you about this picture,” Danny DeVito chimes in. The actor stands about four feet nothing, and from the hairline down, he is built like a potbellied stove. He chooses his words with excruciating care. “This—picture—is—the—weirdest—experience—of—my—entire—existence—as—a—human—bean.

“Lemme explain, OK? I’m from New Yock City, see, so naturally I was figurin’ on seein’ the famous, gorgeous countryside around here—Oregon, you know, the Pacific Northwest, all that shit. Well, I end up workin’ straight through for the first nine weeks I’m here, and then finally I get a couple of days off. Terrific, I think—fan-fuckin’—tastic!—and so I run downtown, I rent a car, I score some deli for a picnic and … I couldn’t leave. I drove out here from the hotel for lunch. So help me, I came out here and peeked in the ward at my bed!”

The writer turns at a tiny tug on his sleeve. It is Ronnie the Patient—surprise, surprise—clutching that errant Sony TC-126. Without explanation, Ronnie shoves the tape machine forward and bolts off into the corridor. The rrr, rrr clicks off like a radio in a distant room.

An hour later, a Chautauqua of dementia is rampaging around the nurses’ station. Every crazy in showbiz except Dub Taylor and Sam Peckinpah is queuing up on the set for A and V 108, take one. In ensemble, the actors who portray Cuckoo’s gallery of lames are shatteringly convincing. They hobble around on crutches, carom around in wheelchairs. They wander the ward in flapping hospital gowns, mismatched pajamas, piss-stained Jockey shorts. They belch, fart, scratch their scruffy asses. They call up visions of creatures out of Dante, or the crowd at Spec’s in North Beach.

Nicholson doesn’t look as bombed and strafed as the rest, nor is he supposed to, but he bounds around the set with demonic energy, all snap and brio. He whomps William Redfield on the shoulder, feints punches at Brad Fourif and Vincent Schiavelli. He tickles fingers with Sidney Lassick and Will Sampson, whispers something obscene to DeVito, laughs aloud at the sight of Michael Berryman and Delos V. Smith, Jr. Skidding to a halt, he waggles his fanny at Phil Roth and puts the arm on Scatman for a cigarette.

“C’mon, B.S., a nail—a nail.”

“Nothin’ but tobacco in that, Jack. Need a light, too, do you?”

“Naw, I got this here little Cricket—”

“I could fan your ass, you need a little suction. Just say the word—”

“Not necessary at all, B.S., but it’s a real pleasure to see you here. Welcome to the stairway-to-heaven party.”

Scatman squinches his eyes shut, flings his head back, croons, “We’ll—build—a—freeway—to—the—stahs….”

“Ah, B.S., you’re a rock to me—a rock to me. The Louis Armstrong of the tenor guitar.”

“Say what?”

“And—I sometimes suspect this—the father of black comedy. Am I correct?”

Nicholson talks and eats and turns out to be exactly what he looks like: a personable black Irishman from Pickup Truck America—a stand-up guy who played schoolboy sports in New Jersey, who got smart, who got out, who got to be a star.

“Yeah, that’s correck, Jack. In both senses. Ah-hah, that was your faithful Scatman in the original woodpile. Jobba-dee-wop! So-cony mo-beel! Zoop!”

Nicholson and Scatman continue poppin’ their chops until Forman stalks across the set and positions them firmly in front of the cameras. Both assistant directors bellow the babbling company to order. “Shot—shot!” “This’ll be picture, people. Quiet—shut up!”

The scene shows Nicholson, aka the bad-ass McMurphy, dispensing illicit pills and Jim Beam to his fellow Chronics and Acutes in a spontaneous-combustion midnight revel. Midway through the caper, Scatman/Turkle bursts in on the group, sputtering, outraged: What the shit’s going’ on here? McMurphy, you motherfucker, get outta here—alla you motherfuckers! G’wan, I don’t wanna hear none of your crazy shit! Get your asses outta here! Pron-toe!

The dramaturgy goes dit-dit-dit, but a light bank blows and Forman blows with it: “No, no, no, NO!” Two more scuttled takes and everybody is yelling—Nicholson, Scatman, Forman, the Chronics and Acutes, even a grip or two.

During the interminable delays, Scatman entertains the idlers on the side lines: “Gentlemen, I’ll show you a tough one. Ver-ry difficult, so watch closely. My impression … of a lighthouse in the middle of an ocean.” Slowly, he pivots in a circle, flapping his mouth open and shut at ten-second intervals. When the cackles hit high C, Scatman mock scowls and snaps his fingers impatiently: “Aw-right, cut the shit and levity—who’s got a cigafoo around here? I’m in need of a nail! I need a nail bad.” Grinning, he accepts one of Nicholson’s filter tips.

Nicholson starts hopping up and down on one leg. “Give us some kind of move over here, will ya?” he catcalls to Forman.

“HEY, MY-LOS!” Scatman brays. “You remember ol’ King Solomon? Man said there’s a time to dance and a time to grieve … atime to harvest … and a time to GET THIS MOTHERFUCKER ON THE ROAD.”

“Yeah,” Nicholson yowls, “let’s shoot this turkey!”

“Wait a minute, though,” Scatman mutters with a frown, “have I got time to go wet? I got to go wet.”

Nicholson continues to hop in place, but he shifts to the other leg. “B.S. … Benjamin Sherman ‘Scatman’ Crothers. By god, you look like the real thing, B.S. What number is this for us?”

“Our third masterpiece together, Jack. The first was The King of Marvin Gardens, and then came The Fortune—”

“Hmm … number three it is. You got a great memory, B.S. You’re a great American.”

“That’s right. FA-ROOK! ZA-GOOF!”

In the commissary, the writer is toying queasily with a serving of vulcanized chicken when Nicholson straddles a chair opposite him. “What’s Hefner like?” the actor asks abruptly. The writer blinks a few times and confesses he’s never had the pleasure. Nicholson seems disappointed at the reply, but he continues unloading his overfreighted lunch tray.

Two Salads. Four buttered rolls. Three side orders of vegetables. Mashed potatoes and gravy. Half a chicken. A glass of iced tea. Two half pints of milk. A double wedge of fruit pie. When Nicholson has all this archipelago of nourishment arrayed in front of him, he sprinkles hot sauce over vast geographic portions of it. Scanning the faces at the surrounding tables, Nicholson spots Scatman. “Hey, B.S.,” he calls out, “you want some speed?” Scatman fields the lobbed bottle of salsa in a chamois-colored palm.

Nicholson makes some amiable small talk, but food is what figures most precious in his life at the moment and he bends to it with wolfish gusto. “Jesus,” he groans, “I haven’t been this hungry”—gnawing relentlessly on a drumstick—“since breakfast.” The writer laughs, feels at ease for the first time since—breakfast. Nicholson talks and eats and turns out to be exactly what he looks like: a personable black Irishman from Pickup Truck America—a stand-up guy who played schoolboy sports in New Jersey, who got smart, who got out, who got to be a star. No, make that a national treasure. Any dumbass can be a star.

Forman resumes shouting and shooting after the dinner hour, but the writer retreats to the downtown hotel where most of the film troupe is quartered. Holed up with a slash of Scotch in handy reach, he studies his notes—fast-draw impressions of the asylum, the movie people, the eerily unsettling rrr, rrr phenomenon. He goes through the material three times and stares for a long while out a window at the rain sweeping the swimming pool.

Around midnight, the writer pulls on his boots and wanders down to the hotel bar to join B.S. Crothers and Will Sampson for some pro-am elbow calisthenics. Sampson is a butter-hearted lad, but he looks like the toughest, rottenest seven-foot Indian in the world, and he savors the part on and off the screen. “I’m mean as hell when I drank,” he growls, “and I drank a little all the time.” “Cheers,” Scatman toasts, “and Roebuck.”

The bar is a sort of color-coordinated bull pen, one of those places where people order things like Salty Dogs. A trash band plays moldy show tunes to scattered bursts of apathy from a table occupied by four or five of the film folk. The Cuckoo hands—a couple of actors, a couple of technicians—are nuzzling close to a round robin of local belles, licking the ladies’ ears and such. “Stunt fucking,” Scatman explains succinctly. “All them cats are married, see—got families and mortgages back in Beverly Hills, but they been up here for three months now and … well, you know. Stunt fucking.”

The band cranks for dear life: “Life is a cab-o-ray, old chum, life is a cab-o-ray…”

“You looked around Salem any?” Sampson asks. “Bah God, it’s weird, I tell you. The city buses all got big signs on ’em that say CHEERIOT, and the suckers shut down runnin’ for the night about seven. Yessir, seven fuckin’ o’clock. And there’s a joint down yonder just off Court Street? Got live midgets rasslin’ in there, and people just streamin’ in to see it. Christamighty, three and a half a head. I call that flat-out purr-verted.”

Scatman gargles egregiously of the grape and pretty soon sinks face down in the sea of glasses on the tabletop. This doesn’t inhibit some tub-butted dentist and his harpy wife from force feeding their way into the booth beside him, gabbling like loons.

The harpy says she’s a member of some civic committee that brings in chamber quartets and Henry Fonda as Clarence Darrow (a last-minute cancellation, that one, and God bless Pacemakers), and she enjoys celebrities just ever so much—they “tone up little old Salem.” In light of his present assignment, she regards the writer, even, as a sort of crypto-Somebody, so she snaps her beringed fingers at the hot dog who’s dispensing the busthead—she’s buying this round, by jingo, for the glory of Greater Salem!

The writer shrinks away, trying to shun the frumious bandersnatch, but she can’t or won’t dry up. “Why do you use That Word?” she snaps at him sharply. “I would think it would be far beneath someone of your education.” The writer explains. In some clinical detail. Calling on all his vast educational resources. The harpy grows pale and rises to depart in fairly steep dudgeon. The dentist trails along behind her like a strand of floating dental floss.

Scatman snores on, the band chugs on, Sampson removes a burning cigarette from Scat’s fingers. He grins fondly. “I’ve drank many a merciful cup of Christian whiskey with this little gentleman,” the big Indian reflects softly.

At the hospital early the next morning, the troupe from the bus troops to the nurses’ station, but nobody exactly stampedes to work. The young honey of a blonde who serves as stand-in for the actresses takes up a sitting-Shiva position by a window, staring gloomily out at the gusting rain. “I feel crummy,” she wails. “I woke up in the wrong crummy room.”

Several of the technicians whip together a card game, others nurse on coffee mugs or take turns bashing a soggy punching bag. “Umm, umm,” Scatman clucks, “if Brother Zaentz was up to see all this big-bucks talent fuckin’ off out here, he’d weep like a limbless orphan.”

Bill Butler, the cinematographer, arrives on the set seconds in advance of Forman, and the crew heaves to lustily. Butler is silent, bearded, monkish in appearance. He talks to nobody except his camera operators, and then in tones so low that no one can overhear. The workmen give him a wide berth.

Scatman is wearing dark glasses and Michael Douglas cackles fiendishly at the sight. “Fell in the vinegar again, huh? How long you plan to wear the blinders, Scat?” “Till my eyes congeal, man.”

The actors on call for the morning’s routine pickup shots labor in ten-minute bursts, then dawdle for a couple of hours. They doze in chairs, bullshit one another outrageously, pass around the Hollywood trade papers. They gab endlessly about the stars (“Raquel got famous by inventing this zipper that wouldn’t close, see”) and in chorus they rattle off more household names than the Yellow Pages, but their gossip isn’t meant to be smart or, in most cases, even unkind—it’s just all they know, all they care about. It’s like reading the trades. The damn things appear there in front of them—they didn’t plan it that way.

“Bright little turn there, turkey. Take a load off.”

“Make that Mister Turkey, if you please.”

“And I told that broad and her mother both, I says, ‘Don’t let the door hit you where the dog bit you.’ It got real quiet after that. You could’ve heard pissants walkin’ on ice cream—”

“Shit, yeah, I done time in the Service, sonny. I worked for Standard Oil for ten years. Scobba-dee-zoot!”

“Ah, the Scatman cometh—never quiteth, in fact. I thought he was a dream of my youth, you know—like J.D. Salinger—”

“Would you believe I saw Roy Rogers on the box last night?”

“Sure, the singing cowboy’s always with us. Look at Dennis Weaver.”

“I wonder if Nixon ever ran off a print of Save the Tiger.”

Somebody arrives with the news that Aristotle Onassis is dead.

“Christ, too bad, too bad … but that leaves Jackie in line for half a billion.”

“BOO!”

“So what’s to crab about, chum? That’s just takin’ poon and makin’ it pay.”

Ronnie the Patient sidles up to the writer in the corridor, offering to show some snapshots of his fiancée. The girl in the photos is sweet-faced, chubby, having fun on a picnic. Ronnie says she is a fellow patient over in the Women’s Facility and he loved her the first instant he saw her.

Rain peppers the windows in the commissary. The writer is bent over his Efficiency Reporter’s Note Book No. 176, recording some notes at one of the long tables. He block prints:

First met Kesey in ’62, Menlo Park. Savored his book but put off by The Author. Figured him for a benign Manson, although didn’t know the term back then. Neal Cassady also present that afternoon, chasing Stanford girls through the underbrush. Didn’t catch any.

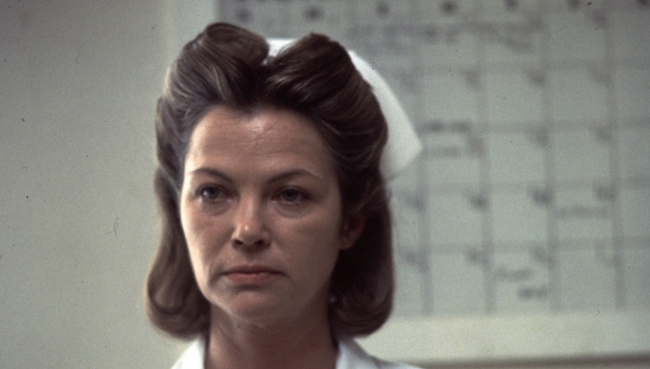

Reminded of this by brief encounter with Louise Fletcher, who plays Big Nurse. Inspired casting. Not a big-bazoomed hag but a young, petite hag, chillier than a blue norther. Had no impulse to linger with her beyond bare amenities.

Crazy factor here is strong enough to siphon gas. Take Delos V. Smith, Jr. (Puh-leeze!) Smith was friends with Monroe at Actors Studio, intimates he has loads of skinny on her—tapes, letters, etc. Politely evasive about it, though. Maybe if I—

The dining hall is empty except for the writer and the coffee attendant—and here comes that rrr, rrr again, higher pitched than before, quantum scarier, too—a sound full of blood rage and murder foul. It clicks this time: It’s Lawrence Talbot turning into the Wolfman … rrr, rrr … and here comes that brawny kid with the purple birthmark banzai-charging across the tatty linoleum with a wet mop raised high above his head like an ax, and whop!—he flails it down slosh on the writer’s instep.

The writer glances up only long enough to see too much white in the kid’s eyes, then resumes block printing. He block prints the word help 73 times. Man flop a wet mop on your boot down where the writer grew up, you generally jump on his bones. But this is different. This is the Oregon State Playpen for Bent Yo-Yos & Mauled Merchandise.

Five minutes later, the rrr, rrr has leveled off to a sullen drone and the kid has mopped his way to the far side of the room. The writer rises, measures his steps to the door. Out in the corridor, he takes a deep breath. Another.

Out of a mixed sense of protocol and craven dread of underachieving, the writer braves the commissary again an hour later. Nicholson is in the chow line, bellying up to the steam tables like a famished wolverine. The actor smacks his chops over the shit-and-shucks cuisine, orders a little of this, a whole lot of that, and pauses undecided before a vile-looking vat of boiled okra. The writer glides up behind him, coughs discreetly and says for openers:

Hiya, Jack….Gee, listen, we’re going to have to meet stopping like this.

Inexplicably, it comes out that way. Nicholson half-turns and cocks his head to one side, his expression hang gliding somewhere between disbelief and morbid curiosity. He picks up two dishes of the boiled okra and moves along. The writer trails Nicholson into the dining area and asks the actor if he might be available to sit and talk seriously sometime.

“Can’t say, pal,” Nicholson says around a quarter-pound chaw of Swiss steak. “Why don’t you ask my agent about it?” He mentions a name and number in Beverly Hills.

The writer goes back to the hotel in the rain and experiences a mild epiphany in the bathtub. Up to his glottis in Mr. Bubble, he realizes he can’t think of anything more he wants to know about Nicholson—nothing at all. It occurs to him that madness upstages all creatures great and small, and maybe in its wicked varieties of mystery, it, too, is a national treasure—purr-verted, of course. Rrr, rrr….

The writer dresses, shit-cans the Beverly Hills agent’s phone number, makes reservations for a flight home and journeys down to the bar, where he immediately encounters the harpy. She is sans dentist tonight and all gussied up to party in a $300 pants suit the color of kitty litter. “My dear,” she exclaims, “how marvelous to see you again. How’s your little story coming along? I’ve never read anything of yours, but I’ll bet you’re right up there with Miss Rona. Oh, I’ve always been a sucker for talent. A sucker, know what I mean?”

Her name is … should be … Bambi. Late in the evening, she is sitting in the hotel saloon with an actor escort, the writer and a roustabout from the film company. Bambi is a sleek sloop of a girl with an ozone-charged voice and an original face. The writer takes her for an actress or maybe a model.

Bambi’s actor companion is drunk, has been for hours. Pretty soon, he can’t see past his glasses. He wobbles away into the cab-o-ray darkness without explanation—none needed. Bambi shrugs and slides around next to the roustabout. “I’m Shelley Winters’ daughter,” she announces theatrically. “Well, not really. I mean, I don’t believe that, but my mother does. What can I say?”

When the Mixmaster band unplugs for a break, Bambi is on her feet. “Come on,” she urges, “I know a boite just down the block.” A boite? “You, too,” she says to the writer.

A boite, you bet. A poured-concrete bunker with dime-store Modiglianis on the walls and a singer who knows all of Neil Young’s gelatinous repertoire. “Far out,” the roustabout whoops, hanging on every quavery verse during a millennium-long set. Facing away from the others, the writer noodles in his Efficiency Reporter’s Note Book No. 176—fantasizes that he is on the verge of grasping something momentous about the lunatic tropisms of Hollywood, of America….

The Neil Young manqué takes his bows to the sound of two or three hands clapping and the house lights flash up. A waiter bends near and asks the roustabout and the writer to please remove their goddamned ladyfriend from the goddamned premises. Bambi, as it happens, is juiced to the tits—knee-walking blotto. She has been downing double gins on the sly for the past hour, the waiter says, and the tab comes to $23.80.

The roustabout and the writer steer Bambi out onto the rain-slick sidewalk and clumsily maneuver her toward a steakhouse where the roustabout says she works. “Yeah, she’s a waitress, man,” the roustabout grunts, sucking for breath. “I thought you knew her in front. Shit, what a deal.”

Two blocks of towing a rudderless sloop through choppy weather and Bambi’s boss spots the approaching convoy. He tears out of the steakhouse, his face changing colors, his arms flailing. “I’ll take the cunt home,” he snaps, “but don’t bring her in the gah-dam ca-fay.” The man drives away with Bambi unconscious beside him in a mud-spattered Datsun.

“Sonofabitch, I could’ve scored, too,” the roustabout complains. He does a couple of quick knee bends to ease the kinks, then shrugs philosophically, “Well, that’s stunt fucking for you. Always chancy.”

The teamster who drives the writer to the airport the next morning chews tobacco and lives in mortal fear of the patients at the state hospital. “Lots of folks are fucked, you know, but especially your nuts. I mean, makin’ a movie with all them basket cases hangin’ around—what kind of nigger riggin’ is that? Listen, my friend, I’ve personally known a bunch of them creepos out there since I was in first grade, and you can take my word for it, they ain’t fit to be runnin’ loose. You notice that beefy kid in the commissary, the one got the birthmark? Wonderful guy, swell guy—the mayor oughta give him a kiss and a medal. Fucker killed four people with his bare hands.”

About 200 miles into the Rockies, the writer’s fantods stop vibrating and over a healing beaker of brandy he monitors a cassette tape of B.S. Crothers spritzing, clowning, blowing the shit.

You ever smoke these things? Lord, we used to smoke this stuff back in ’29—smoked it on the street and nobody ever bothered us. Ace leaf was common as dirt down yonder in Texas. We used to go into them fuckin’ Mexican joints where they sold hot dogs and shit? They’d say, “You want some mmm-mmm?” I’d say, “Yeah, lemme have a quarter’s worth.” Guy’d give me a penny matchbox full, already manicured, and a few papers, and it would roll out to about ten things. For a quarter. Godamighty, man, it was good….

Ah, that Scatman—skee-zack! Another of your basic national treasures.