In the summer of 1968, John Berendt, a young associate editor of Esquire, accompanied three members of that magazine’s unusual team of reporters to the Democratic National Convention, held that year in Chicago: Jean Genet, William Burroughs and Terry Southern. (Esquire also dispatched the more sensible, John Sack, as insurance.) It was all part of Esquire editor Harold Hayes’ scheme to land literary gold. Well, the ’68 DNC became famous, and the three literary gents delivered appropriately cryptic and weird reportage, interesting for sure, but nothing great. The three amigos didn’t deliver anything nearly as powerful as Berendt’s own observations, which appeared the following year in the paperback anthology, Telling It Like It Was. Berendt went on to enjoy a long magazine career and achieved his own fame as the author of the Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.—Alex Belth

Unnoticed amid the confusion of arriving delegates and newsmen in the lobby of the Sheraton-Chicago Hotel, three writers met to have a drink: Jean Genet, William Burroughs, and Terry Southern. They were there to observe the Democratic Convention, two days away, and to act as reporters for Esquire magazine.

For Genet, this was his first visit to America and it was a trip that he had been frank enough to say he dreaded making. Americans by the million may have read and respected his novels and been electrified by his plays, but Genet could not forget that the American government had refused to give him a visa only a few years before. It had been worse than that: the American embassy in Paris had given it to him and then called the next day to tell him they wanted it back, that on second thought he, Jean Genet, a man preeminent in the world of Letters, was in the eyes of the U.S. State Department primarily a former thief, convict, and admitted pederast—not welcome in the States. It.is possible that Genet agreed to come to the Democratic Convention having been persuaded by the reassuring likelihood that he would see America at its very worst.

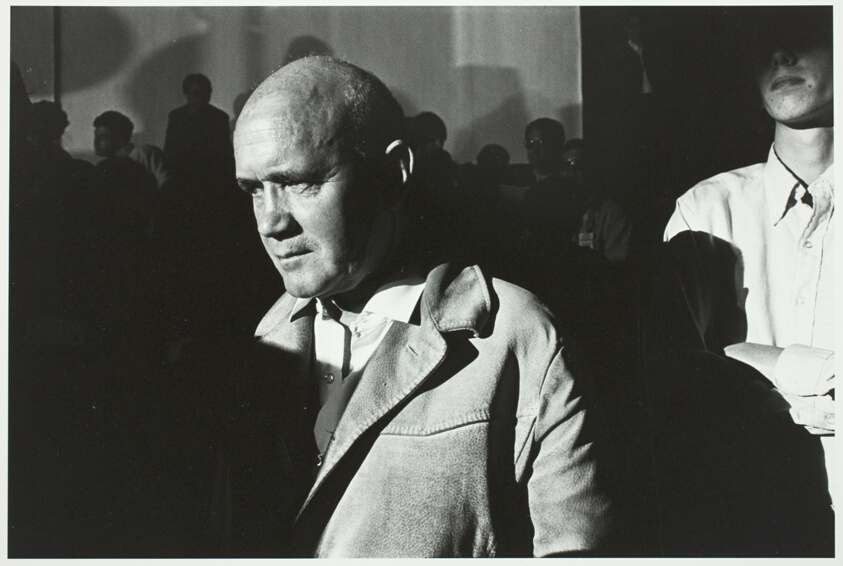

On his way to Chicago, Genet stopped off in New York, where he was joined by Richard and Jeannette Seaver. Seaver, who is the managing editor of Grove Press, was Genet’s publisher here and would act as interpreter and translate the diary Genet was to keep in Chicago. Jeannette, Seaver’s young French wife, beautiful and hip, would also interpret for Genet, who spoke no English. The day before leaving, they came to Esquire’s offices to have lunch with the editors of the magazine. Genet, somewhat elfin-looking in an open-collared white shirt, corduroy slacks, and a suede jacket, was amiable and warm, and startlingly candid.

“What are your impressions of America?” someone asked him.

“I am a guest here, and I shall not abuse the hospitality,” he said.

“Feel free,” one of the editors interjected, “we are hardly super-patriots.”

“Prove it,” Genet insisted.

“Well, we asked you to cover the convention, didn’t we?”

“Oh no,” Genet replied emphatically, “My name is known all over the world. You asked me out of snobbery.”

For William Burroughs, going to Chicago meant returning to a city he had not seen for more than twenty years. In fact it meant a return to the country from which he had chosen to expatriate himself. Burroughs had spent much of his life outside the United States and had been living in London for years. This would be for him, as for the others, his first American political convention. But as he walked through the crowded lobby Saturday evening, he looked less like a man who wrote about orgy scenes and drug trances than like a delegate from Kansas. His long pale face was absolutely deadpan. He wore a brown suit, black shoes, and a fedora with the brim turned up all around. William Burroughs’ appearance prompted those who saw him to make analogies. Some of the most apt likened him to: a bank teller, a mortician, Buster Keaton, a bookkeeper, and, perhaps because of the hat, Edith Sitwell. Six o’clock in the Sheraton lobby was eleven o’clock at night for Burroughs: he had just flown all the way from London.

For Terry Southern, the Chicago convention represented a week-long break from the making of his new movie, The End of the Road, which he had been shooting in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. “Oh, I’ve read your Candy,” a lady said to him as he rode up the escalator, “and so has my eleven-year-old daughter.”

Southern’s attention to the day-to-day political realities of the convention was threatened by an enticing schedule of side activities going on around him, like, for instance, the Kiwanis Little Miss Peanut Finals which was to take place in this very hotel, and which at 6 P.M. Saturday was fighting for the uppermost place in his mind.

The three of them stood in the lobby, Genet, Burroughs, and Southern, unnoticed—that is virtually unnoticed, the exception being for a semi-clean-for-Gene churl who stood at a distance and muttered to his girl, “God, I bet you could score a kilo off those guys here and now.”

A plumed waitress approached us in the hotel’s Golliwog Room and wagged her finger, “Ties, gentlemen.” So we settled in the less elegant Downstairs Lounge for drinks. Genet asked Dick Seaver to translate the Gay Nineties lyrics being flashed on a screen above a noisy piano. In the comer, Terry Southern rubbed his hands together in gleeful mock-anticipation. “Well, Bill,” he said to Burroughs, “How you think we ought to cover this convention? Hyeh!”

“I don’t know yet, Terry, it’s the goddamndest idiocy.”

“I tell you one thing, Bill. Heh! And that one thing is: cy-ni-cal de-tach-MENT. Heh! Yep. Ain’t that so, Jean-Jack,” Terry said turning to Genet. “Can’t you see it, Bill,” Terry went on, “the candidate flips out once he’s been nominated. He gets up there and hollers ‘Hot Damn, Vee-et Nam! San Antone!’ It just freaks ’em out, eh Bill? Suppose old Dr. Benway were the nominee. Hyeh! ‘Hot Damn, Viet Nam!’ ”

The conversation turned to the subject of money and Genet joined in, referring always to Southern as “Folamour,” Strangelove in French. Genet felt that money was inherently evil; he liked the idea of the hippies burning it. Burroughs suggested such thoughts were Irrelevant anyway since the American currency was fore-doomed to crash. “That’s the main issue of this election, isn’t it?” he concluded after a lengthy and obscure discourse about the dark future of the dollar. “That, civil rights, and the war?”

Chicago was a city girding for the unexpected. News commentators spoke about the hordes of hippies slouching toward Chicago, 200,000-strong by some estimates. Nervous policemen were out in full force with riot gear.

“Dunno, Bill,” said Terry, having a bit of fun with the unflappable Burroughs, “But there’s a man been seen in the lobby of this very hotel you ought to talk to about it. John-Jack Galbraith, that man is John-Jack Gal-braith!”

Afterwards the party split up. Genet pronounced the approaching convention rigged, silly, and dull and said he wanted to go see “Les yeepees.” So the Seavers took him to Lincoln Park and !he hippie Old Town section along Wells Street. Terry, Burroughs, and I went to dinner in the near north shore after which, it being the equivalent of 4:30 A.M. in London, Burroughs went to bed and Terry and I continued on.

Chicago was a city girding for the unexpected. News commentators spoke about the hordes of hippies slouching toward Chicago, 200,000-strong by some estimates. Nervous policemen were out in full force with riot gear. Late that night David Dellinger, head of the National Mobilization Committee, spoke to Terry of the police harassment and the mounting tension. “All we want to do is make our feelings known,” he said, “to present ourselves in great numbers before the Democratic Convention. We don’t want violence, but it’s beginning to look as though it’s going to be visited upon us anyway.”

The next morning, Sunday, Mobilization leader Rennie Davis announced that the activities for the day would include demonstrations outside the hotels to welcome the major delegations, and a confrontation at eleven that night between the Yippies who wanted to sleep in Lincoln Park and the police who promised to enforce the curfew. “We were thrown out of Lincoln Park last night,” he said. “Tonight we’re staying.”

But Sunday was also the day Eugene McCarthy was arriving at Midway Airport, and Genet, Southern, and Burroughs went to watch him arrive. The crowd on hand was large and exuberant, perhaps 15,000. Genet, in good spirits, wore a McCarthy button and chatted excitedly as he stood on a flat-bed trailer reserved for the press. “For the first time in my life I’m not ashamed to be a member of the press,” he said. “Nobody knows who I am, and I’m not being given any special privileges because of my name.” He watched with fascination as a mime troupe in painted faces moved through the crowd acting out extemporaneous scenes in guerrilla theater fashion. Burroughs, also wearing a McCarthy button, devoted most of his attention to a portable tape-recorder with which he was recording crowd noises.

It was a long wait, however, and when McCarthy at last arrived, the sound system broke down and his speech was inaudible. We ate lunch at a nearby hamburger joint rather than fight the traffic back downtown, and while we were there a contingent of plainclothesmen came in and lined up at the counter to order. “Well, at least they are polite,” Genet said. “They wait their turn. In France, De Gaulle’s guards would shove their way to the head of the line.” Genet wanted to talk to them, so I asked one if he would consent to an interview, nothing specific, just general. He said he would not. I asked if his lapel pin meant he was from the F.B.I., Secret Service, or some local agency. “Buster,” he said, “We’re Feds, and we’re not talking.”

On the way back to town I asked Genet what he thought happened to the mind of a man, however good, who was greeted by cheering throngs every day for eight months, as McCarthy had been. Genet said that much as he admired McCarthy’s views, he thought he detected a little “putainisme” in his face. “And now let me ask you a question in return,” he said. “What has happened in the mind of a man who makes cars and chooses to name them ‘Galaxie?’ ”

We decided to make an effort to talk directly to the candidates. Humphrey, we knew in advance, would be almost impossible. In New York the week before, Genet had mentioned that he had ten questions to ask each candidate, and I had called Humphrey’s press aide, Norman Sherman. “Is he going to write an unfavorable piece?” Sherman had asked. “You know we were highly pissed off by that cover Esquire did last year showing the Vice President as a dummy Sitting on Johnson’s knee.” I said I could appreciate his feelings. “So maybe you can understand,” Sherman said, “that I’m disinclined to fuck around with Genet.” I appealed after that to a committee called Arts and Letters for Humphrey, whose membership list, when compared to a similar committee of McCarthyites, seemed rather small, intimate, and second string. And possessed of limited influence, it turned out. They couldn’t get near the candidate, even by phone.

The response of the McCarthy staff members was predictably the opposite. A security girl at the Hilton ushered us into the McCarthy delegates lounge, normally closed to all members of the press, and McCarthy’s press secretary, Don McClure, assured us that McCarthy would rather speak to Genet, Burroughs, and Southern than to any news reporter. McCarthy, however, was busy with delegate caucuses uptown and after waiting over an hour, we made excuses and left. What sort of questions did Genet have in mind? On the way back to the car we happened to encounter a crowd in front of the Blackstone surrounding another candidate, Senator George McGovern. “Oh, wait,” Genet shouted to Jeannette Seaver as he pushed his way into the crowd. “I must ask him a most important question. Please ask him if he thinks he is psychologically and intellectually suited to be president of the country. And if so, how he knows he is.” But McGovern was gone before the question could be asked.

The confrontation between Yippies and policemen in Lincoln Park did not materialize that night. The whole build-up had been a sham on the part of the Yippies who left peacefully according to plan at eleven. Walking along Clark Street, bordering the park on the west, Genet noticed several dozen youngsters bedding down for the night in a backyard. “They need help,” he said, “such angels.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out a thick wad of bills, shoved them into the hands of a long-haired youth. “Hey man, you’re beautiful,” the boy cried and kissed Genet. “This buys all of us our supper.” The Yippies crowded around, hugging and kissing Genet. One gave him a “Yippie” button, another gave him a Yippie ring with the two-fingered V sign. Jeannette asked Genet if he wanted to go into the back yard and talk to them. “No, no,” he insisted. “They’re miserable and cold and I don’t want to pry. And please, don’t tell them who I am.” We walked on.

Genet and Burroughs were tired and went to bed. The rest of us followed Terry to a small party at “Hef’s.”

Allen Ginsberg joined us at the hotel and for the first time in his life met Jean Genet. The meeting happened to take place “underground” in the hotel’s basement garage—a metaphor which pleased them both.

Hugh Hefner was not at home when we arrived, but a dozen guests were casually assembled throughout the house. Borden Stevenson, wearing black patent leather slippers, chatted with Hugh O’Brian in front of the fireplace. John Chancellor of NBC, and David Brinkley toured the house and settled in a dark den downstairs, which one entered by a firepole or the stairs as one chose. Warren Beatty was pouring a drink at the bar, while an off-duty bunny made several studied passes in his direction all without success. “That’s Warren Beatty,” said Chancellor, “He’s really a nice guy. Want to go over and talk to him?” “No,” said Brinkley. Eventually the room emptied as guests moved upstairs, and Chancellor, the last to go, glanced at the firepole. He looked around, clutched the pole and pulled himself up, strained, grabbed with the other hand and fell in a heap onto the cushions on the floor.

Upstairs, Terry Southern was talking with New York delegate-cartoonist Jules Feiffer, who was not staying with most of his delegation at the Sheraton, but here in Hefner’s mansion. As was columnist Max Lerner, who was frugging in the living room with a young girl. His son Steve, covering the convention for the Village Voice, went down for a dip in the pool. Meanwhile, on the couch, Defense Department whiz kid Adam Yarmolinsky listened attentively while a Playboy bunny earnestly told him about the rigors of… night school.

It wasn’t until 3 A.M. that Hefner arrived, and with a Pepsi and pipe in hand, took up a position by the fireplace. Almost immediately, Yarmolinsky uttered a remark about Playboy’s audience being old, middle class, and materialistic, and Hefner swung into a defense of the magazine. “We cover what people care about, namely the bedroom.” At this point, Terry nudged Gail Gibson, his girl friend, who suggested to Hefner that he open his house to the Yippies who were being thrown out of Lincoln Park only a few blocks away. “I think you’re confusing the Playboy Club membership with the magazine’s somewhat younger readers,” Hefner said, dodging Yarmolinsky’s challenge and ignoring Gail completely.

“But you wouldn’t have to let them upstairs,” Gail persisted, “they wouldn’t smell up the place much.”

“Well, I think it’s more a matter of space,” Hefner replied. “I couldn’t fit them all in.” As she left, when she was out of range of the hidden closed-circuit cameras in the front hall, Gail stuck out her tongue and uttered a long, loud sustained raspberry.

Monday morning Allen Ginsberg joined us at the hotel and for the first time in his life met Jean Genet. The meeting happened to take place “underground” in the hotel’s basement garage—a metaphor which pleased them both—and from there we proceeded to a Yippie press conference on the grass in Lincoln Park. There had been a touch of violence the afternoon before in Grant Park (Stew Albert, a Berkeley radical, eloquently described the bloodbath by bowing silently to the cameras and displaying a nasty gash in the top of his head), and Ginsberg and Genet were the only two to sound notes of relative nonviolence.

“I’ll march to the Amphitheater on Wednesday,” Ginsberg promised, “but only if all the Yippies will take off their clothes in front of the Conrad Hilton and go naked.”

Burroughs stood on the periphery, still looking like the delegate from Kansas, taping odd moments of the conference, when a police officer walked up to him and muttered in his ear, You’re wasting your film on shit like this.”

Genet got up to speak, and Ginsburg translated. “First let me say that I took a lot of Nembutals last night to forget I was in Chicago. Forgive me if I am a little groggy.

“You children are living the life I used to lead, you know, and you are beautiful. Someday the buildings of Chicago will be covered with flowers and trees: then they too will be beautiful. But be careful now to guard your rights. “You have a right to sleep in the park, to wear long hair and imaginative clothing. Certainly you are more pleasant to look at than the cops with their blue helmets, plexiglass masks, and revolvers. Your very presence here is a fitting antidote to the silly convention going on downtown.” There were cheers. Hands went up with the peace sign, and the gathering rose to its feet, forming a ring in solidarity. A young girl rushed up to Genet and smothered him with kisses. He hugged her back and called to Ginsberg, “Allen, be sure to tell her I’m a homosexual!”

Tension gripped everyone except Burroughs, who said what he really wanted was a drink and headed for the Oxford Club Bar on Clark Street.

On the way back to the car, Genet and Ginsberg walked ahead. Two thuggish characters were following us a distance. “It’s cool,” Ginsberg said, “they’re only my tails. We can shake them just by going to the convention: they don t have passes. Gentlemen,” he called to them, “we’re going back to the Sheraton.”

Back at the hotel, over lunch, Burroughs explained how he intended to use his tape recorder. “Look, man,” he said, “what you do is this: you tape about ten minutes of somebody talking, then you reverse back to the beginning and go forward again, cutting in every few seconds to record bits and pieces of something else. You keep doing this until you’ve made a complete hash of it all. Then you walk around with the damn thing under your jacket, playing it at low volume. It flips people out. I do it in London all the time.” He demonstrated his technique.

At the convention that evening, we sat in a section of the balcony allocated for members of the periodical press. Burroughs was totally preoccupied taping and cutting up the general din of the opening ceremonies. “The tape recorder is God’s plaything,” he said, casting a cold eye upon the proceedings, “and quite probably his last.” Genet talked with Dick Seaver, expressing his utter contempt for the gaudy, meaningless show that was taking place. Ginsberg, softly chanting a mantra, lit two sticks of incense, giving one to Genet and holding the other in both hands, his fingers entwined around it in an intricate Hindu sculpture. Clearly they were all bored. After a half hour of being stared at and photographed, they rose to leave. Ginsberg stood facing the convention floor, raised up both arms, and bellowed, “Hare Krishna!” Heads whirled around; Burroughs, who’d known and fondly put up with Ginsberg’s antics for almost twenty years, winced and then broke into a rare thin smile.

Shortly after eleven in Lincoln Park it looked as though the Yippies were going to be true to their word. There were at least three thousand of them still in the park, milling around in the darkness. Scores, of not-helmeted policemen had gathered at the park’s southwest comer, not preventing anyone from entering, but definitely getting ready for action later on. No one was leaving; quite the opposite: hundreds of people—hippies, high school kids, adults and newsmen—were pouring across Clark Street into the park.

Tension gripped everyone except Burroughs, who said what he really wanted was a drink and headed for the Oxford Club Bar on Clark Street. The rest of us crossed over onto the grass. Ahead of us the vast park was filled with dark moving bodies. It was a cloudy night, made darker because all the lights in the park had been put out. Ed Sanders of the Fugs spotted us and came over.

“What’s happening?” Ginsberg asked.

“The cops have formed a barricade out there by Lake Shore Drive,” he said, pointing ahead into the darkness, “and they’re massing by the hundreds.”

Greater numbers of hippies had apparently massed on the near side of the barricades, and they were clapping, beating metal trash cans rhythmically, and chanting, “Hell, no, we won’t go!” The tension was electric. Ginsberg, Genet, Dick Seaver, Terry, and I locked arms and moved forward through the crowd toward the barricades. As we walked, some of the children recognized Genet. “Hey, wow, Jean Genet’s here,” the word spread. People clustered around us as we moved. A few of them, stoned, stared at Genet as if it were a dream. “I didn’t think he really existed,” one young boy said, his voice miles away. “Oh, beautiful.”

Halfway toward the barricades, Ginsberg began to chant a resonant. “OWWMMMM.” Those around him joined in and soon the whole park was filled with the continuous vibrating note. Remarkably, those at the barricades stopped yelling, “Hell no,” and joined in too. Ginsberg’s chant was having just the effect he had hoped for. As he had told us earlier, he had only agreed to come to Chicago because he felt there was a chance he could reduce the level of violence and talk the Yippie leaders into a nonviolent, non-provocative stance.

“Owwwmmm,” resounded through the park. It was strangely becalming. A hippie came up to Ginsberg and held a spoon out to him. “It’s honey,” he said, “take it.” “What’s in it?” Ginsberg asked, a little hoarse from chanting.

“Honey. It’s groovy,” the kid answered.

“Look, I can’t now,” the poet said. “I’m working.” The situation was touch-and-go. One slight movement from the cops, and a roar of fear would go up from the crowd as they would turn from the barricades and start to flee. A stampede was an ever-present danger. During the first false alarm, cooler heads screamed, “Walk, Walk, Don’t Run, Don’t Run!” and tried to put a brake on the frantic mob running blindly through the dark. Gradually more and more took up the cry to “Walk!” and the panic subsided. Ginsberg tried another tactic. He withdrew a hundred feet back from the barricade and sat down. Within moments he was surrounded by two hundred youths all chanting. “Owwmmmm.”

Another roar went up at the barricades, and as the people started to run, those around Ginsberg held their ground, yelling, “Sit Down! Sit Down! They can’t hurt you if you sit down!” Others who had been standing around watching, acted as marshals, spread out their arms, and shouted for those who were running to stop it.

At 12:30, another roar sounded at the barricades. But this time it was different: louder, higher pitched. This time it emanated from the full length of the barricades, not just one point. Hundreds of people ran toward us in a human wave. The ground thundered with running feet; everybody ran, screaming, falling into each other in the dark. The seated ones leapt up and stumbled in the direction of Clark Street. The scene was one of mad, stark terror. People ran into trees, fell into pit-holes, grabbed onto others for help. Dick Seaver and I took Genet by the arms and started running. Tear gas grenades landed among the crowd, exploding and throwing off a choking whitish smoke. A glance backward and one saw an army in blue advancing toward us at a run, swinging clubs at those who had fallen behind. Moments later, the crowd spilled out of the dark into the hopeful sanctuary of Clark Street. But hordes of policemen charged out of the park into the street, plunging into the crowd and swinging their clubs blindly at people who now had nowhere to go. Bottles and rocks rained everywhere, smashing against buildings, shattering windows of cars trapped in the street. A patrol car was virtually demolished as the cops persisted in rushing at the fugitives they now held at bay. A boy picked up a handful of stones, threw them, and was fallen upon immediately by seven club-swinging policemen, grunting as they swung with all their might, covering themselves and their nightsticks with blood. A newsman flashed a picture of it and three cops ran at him and pulverized his camera.

Up and down the street, gangs of cops raced into groups of fleeing civilians, clubbing wildly, darting in and out of cars now deserted by their terrified drivers. A policeman carrying a shotgun ran past us into three boys, lost his balance, and fell on his back. In a rage he jumped up, grabbed his shotgun by the muzzle, and swung the butt end at them like a baseball bat, narrowly missing their heads. As one of them dashed past him in desperation, he lashed out again, missed, and brought the butt down on the sidewalk with a hideous crack. The three of us backed into a vestibule for safety and stood there with four other people. We hadn’t been there a moment when.four policemen charged in and were upon us. “Communists! You fucking commies! Get the hell out of here,” they screamed at the top of their lungs “Press!” shouted a man near the door.

People who lived upstairs were calling to us to come up; It was still dangerous in the street.

“Press my ass!” shrieked one of the cops, bringing his club down on the man full force and literally throwing him against the door out into the street. He pursued the man, kicking him and pausing only to slam his club across the shoulder of a young girl in a nurse’s uniform.

“God damn you,” a cop still in the vestibule shouted at us. “You don’t live here; get the fuck out before I let you have it!” Terrified, I held Genet, pressed against the wall. The cop was trembling with rage, his face horribly contorted with hate. He raised his club above us, screaming incoherently.

“Stop,” I shouted, “he’s an old man. Don’t!” We made a move toward the inner door, and the policeman directed his assault on a young boy just entering the hall from the outside. The vestibule was finally empty of policemen.

“Did you see the look on his face?” Genet asked. “Trained actors could never duplicate it.”

People who lived upstairs were calling to us to come up; It was still dangerous in the street. On the second floor a young Negro girl opened her door and asked us in.

“My God, it’s horrible,” she said.

“You aren’t surprised, are you?” asked Genet “They’ve been doing that to the blacks for years.”

Clashes were still raging along the street, so we left out a back stairway into a parking lot and through it to Wells Street. It seemed quiet at first; there was a police blockade at the north end, and we walked toward it intending to pass through to pick up our cars. Suddenly the police started running toward us, laying down tear gas. We turned, only to find more policemen coming the other way. Quickly we filed through a doorway off the street into a small high-walled front yard, and slammed the door. Beyond the wall there were the same now-familiar sounds: shouts, crashing glass, running feet. We waited. When the clamor subsided, we left, by twos so as not to arouse the police. A boy who’d parked his car outside the occupied area drove us back to the hotel.

It had been a bad night for Chicago and a squeaker for the progress of Western literature. At the very moment Jean Genet had stood up against the wall, menaced by a club-wielding, half-crazed policeman, Terry Southern had ducked into an entranceway two doors down under a shower of broken glass; Allen Ginsberg had paused briefly in the middle of Clark Street for a last ditch “Owwmmm” before fleeing into the Lincoln Hotel where he was staying, and William Burroughs, having left the Oxford Club Bar, was flushed out of the back of a parked truck on Clark Street where he’d been invited by some of his young hippie-head fans for a smoke.

Genet padded into the Seavers’ room at eleven the next morning in his kimono. He was incensed by what had happened the night before and insisted on issuing a public statement decrying the actions of the police. Burroughs soon joined the enterprise along with Terry. Allen Ginsberg said he was expected over in Lincoln Park for a songfest but would come over at three. By late afternoon the statements were completed, and by happy chance there was to be an Un-Birthday Party for Lyndon Johnson that evening where they could be read to an appreciative audience.

The “Party” was held at the Coliseum and it was a rousing affair M.C.’d by Fug Ed Sanders and attended by 6,000 youthful anti-Johnsonites who burned draft cards while Phil Ochs sang,”The War is Over,” roared with delight at the anarchistic antics of Abbie Hoffman, and cheered respectfully when first Burroughs then Genet (reading in French, translated by Seaver) read their statements of protest. Terry Southern shyly begged off, and his speech and Ginsberg’s (who had almost no voice left) were read by Sanders. The police stayed, practically out of sight.

Our plan afterward was to go to the convention but Genet had a different destination in mind. “Le parque.” We got there just after curfew.

The crowd was thinner this time, as many of the Yippies had split to Grant Park to demonstrate in front of the Hilton. But the tense atmosphere.was the same and the police barricades were again positioned along Lake Shore Drive. Tonight several hundred members of the clergy had joined the hippies and they were holding services beneath a twelve-foot wooden cross. The children were singing Kumbaya, and the clergy was pleading for calm.

“Isn’t it beautiful,” Ginsberg said. Soon we would see if the influence of Christ could accomplish what the mysticism of the East had failed to do the night before. Hymns versus Owwmms.

At twelve-forty, divinity notwithstanding, the police attacked again. This time the tear gas was heavier, sprayed from street-cleaning trucks, and motorcycle headlights advancing through it gave the billowing smoke a reddish-yellow glow as if the park were on fire. Hippies paused midflight to look behind them in awe at the lurid sight.

The carnage that ensued needs no verbal description: the whole world was watching.

Tonight, according to plan, we locked arms and ran together, directly toward the lobby of the Lincoln Hotel—Burroughs fumbling with his tape recorder all the way. The crowd in the lobby, coughing and bleary-eyed from the gas, dabbled water over each other in clumsy attempts at first aid.

“The hippies are angels,” Genet was saying, tears rolling down his cheeks. “They are too sweet, too gentle. Someday they will have to learn.”

Eventually, when the lobby became more crowded and gaseous, we went upstairs to Ginsberg’s room. There we watched the tumultuous end of that day’s session at the convention until Ed Sanders came in and told us that the cops were really uptight; there had been some shooting.

By Wednesday, Chicago was a city of anger barely contained. Virtual martial law had descended overnight, and the battlelines were clearly drawn—not that there was any doubt who’d win. Busloads of policemen were seen being moved about the city; jeeps with mounted machine guns drove in the streets, mixing with regular civilian traffic, and rows of police and Guardsmen ringed the Hilton Hotel. “By God, they’re the scruffiest soldiers I’ve ever seen,” Burroughs sneered as he reviewed the troops along Michigan Avenue. “I don’t know,” said Genet. “I prefer the SS after the Second World War. They looked worse.”

So much tear gas had been used that there was a faint tinge of it in the air everywhere. Up in Lincoln Park, the police kept the gas at a noxious level by lobbing it into the park at regular intervals, just to keep the Yippies from congregating. The mood in Chicago was war-like. The convention itself was moving toward its inexorable climax of nominating Hubert Humphrey.

A rally at the bandshell in Grant Park in the afternoon preceded what was to have been a march to the Amphitheater. Burroughs and Genet addressed the throng, Burroughs saying that the System was unworkable and could not be enforced, Genet throwing everybody off-guard by saying abruptly, “It took a lot of deaths in Hanoi to cause this protest here.” Genet, Ginsberg, and Burroughs all planned to join in the “illegal” march and get arrested if necessary. Terry Southern, his posture of “cynical detachment” fading fast, joined ranks with the others, as ready to be arrested as they were. Genet, who was still convinced that the convention was rigged, could not help noticing the profound effect that the activities in the streets were having at last. Four writers who had come to “observe” were now participants, very much a part of the action.

Arrests, of course, did not take place because the march was stopped by rows of police and National Guardsmen before it even got out of Grant Park. The exits from the park onto Michigan Avenue were blocked temporarily as the crowd was repeatedly gassed. We headed away from the throng to the north, where there were no troops, and we were able to leave the park. Meanwhile, down by the Hilton a huge crowd had spilled out of the park and was blocking traffic. The carnage that ensued needs no verbal description: the whole world was watching.

By Thursday Chicago was beginning to get to Genet. Almost all the hotels had been stink-bombed and the putrid odor mingled with the stale scent of tear gas.

Because we felt we had to, we went to the Amphitheater to watch the balloting for president. Genet was totally depressed by it: “These are rubber people; this is a rubber convention.” He slumped down in his seat smiling only at the “Owmming” of Allen Ginsberg. When later on a security guard ejected Ginsberg and an English photographer by the name of Michael Cooper without explanation in spite of their credentials, it was probably not so much because of their unorthodox appearance, as they thought, but because of Ginsberg’s booming “Hare Krishna,” which had interrupted the benediction and made a shambles of the hurried closing ceremonies.

By Thursday Chicago was beginning to get to Genet. Almost all the hotels had been stink-bombed and the putrid odor mingled with the stale scent of tear gas. Litter filled the streets, and the atmosphere of desperation was reflected in the faces of those who’d hardly slept in three days—delegates, campaign workers, newsmen, Yippies, mobilizers, and police. Genet wanted to drive out into the countryside and touch trees, walk among flowers. For several hours he and the Seavers drove, but as luck would have it, they went in the wrong direction and spent the entire day touring the vast industrial wasteland between Chicago and Gary, Indiana.

At 9:30 the next morning, we lifted off the troubled ground of Chicago. In New York, Burroughs went directly to the Delmonico Hotel, asking cryptically if I’d send him research material on the purple-assed baboon. Terry went off to Massachusetts to write, and as for Genet, it should have ended there but sadly it did not.

Genet was obsessed with his predicament of getting out of the country. He had entered, apparently, without a visa and he was convinced he was going to be caught. No doubt the aura of the police state in Chicago had upset him profoundly, and he had visions of falling helpless into the hands of American authorities. On top of that, a series of minor misunderstandings broke him completely. Genet began to think everyone was conspiring against him and telling him lies, and at eleven Friday night Dick Seaver called me to say that Genet was extremely upset. Worse, he was having a temper tantrum. In fact while we were speaking on the phone, Genet grabbed the last few pages of his manuscript and tore them up. The Seavers’ scrambled to get the rest away from him.

At noon on Saturday, Genet met Burroughs and Bernard Giquel of Paris Match for lunch and poured out his grievances against the United States. “Nothing is real,” he said. “Everything is tape recorders and photographs. Reality in America is dead, absolutely finished.” Burroughs and Giquel protested weakly, realizing the futility of it. “I wish I were black,” Genet had said. “I want to feel what they feel.”

At two o’clock, I came to the Delmonico Hotel and saw Genet for the last time. For a memento, I had brought him a large photograph of himself, Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Southern at the Yippie press conference in Lincoln Park. Genet looked at the photograph and tore it down the middle. “Forget Chicago!” he stammered in English. But as he spoke, his valise arrived in the hotel lobby and it meant he was at last leaving. Perhaps more resigned than reassured, he allowed a broad, warm smile to spread across his face—as though nothing had happened. Then he shook our hands and was gone.

[Photo Credit: Portrait of Jean Genet in Chicago 1968 by Lee Friedlander via The Art Institute of Chicago]