In this age of hard sell, when even the most reticent author can be coaxed into a half-hour on camera with Dick Cavett, J. D. Salinger obdurately remains publishing’s invisible man. This is, of course, hard on his admirers, who would like to see him and hear about him and, especially, read something new by him. Salinger doesn’t do interviews; nor does he answer letters, or allow reprints of his stories, or publish.

So it is a shock to see a recent issue of New Letters and find his name on the cover. Had Salinger, after a fourteen-year silence, chosen to come back to print in a university literary magazine with a circulation of less than 2,000? As it turns out, he had chosen nothing of the sort, and therein lies a tale of the most famously uncommunicative of our writers and the vexations, resentments, defiances, and intrusions stirred by his unyielding withdrawal.

The story in the fall 1978 issue of the literary quarterly of the University of Missouri in Kansas City is an authentic Salinger, all right, published by the magazine in 1940 and probably his second piece of fiction ever to reach print.

Entitled “Go See Eddie,” it is impressive but thin, a swift vignette about a young woman with two lovers. On its first appearance nearly forty years ago, the sexual undertones upset some readers, and the former editor, Professor Alexander Cappon, found himself compelled to defend its quality and his decision to print it before the school administration.

Salinger was twenty-one when “Go See Eddie” was first published. The author of The Catcher in the Rye, that splendid modern hymn to tormented adolescence, is now sixty. He does not like seeing his earliest work reproduced. Just the other day, upon learning of the New Letters issue, agent, Dorothy Olding, dispatched a brief note asking who had granted permission for the reprint.

Salinger has never been accessible. Fame overtook him in 1951 with the publication of Catcher, his only novel, and he fled attention just as the frail in health flee the winter cold.

The answer is apt to be complicated. From time to time, New Letters reprints some of its distinguished early contributors, among them William Carlos Williams and Paul Goodman; a good while ago, it occurred to the new editor, David Ray, to do the same with “Go See Eddie.” He wrote to Salinger for permission. Over five years, he is certain he wrote at least three times.

“He doesn’t answer letters,” Ray reported peevishly. “We did a copyright search and found the story had never been copyrighted. We believe it’s perfectly legitimate to brag about our history. I personally believe Salinger has abandoned his public. I asked myself, what’s our responsibility? To Salinger’s quirks, which we don’t respect, or to the magazine?”

The magazine won. For that issue, the usual print order of 2,500 was doubled; eventually, as word spreads among Salinger idolaters and buffs, who apparently still are legion, the entire 5,000 will probably sell out. The professor is aware that, in 1974, Salinger took legal action to halt distribution of a pirated edition of uncollected stories he did not want collected. But Ray thinks this venture hardly falls into the same category of illicit profit-taking. At $8 a year, or $2.50 a single copy, the quarterly is a dependable money-loser. Even if it makes a few pennies from the double printing, Ray argues that the magazine supported Salinger when he was a young unknown, and he has an obligation to make it possible for other deserving new writers to find an audience.

The “Notes on Contributors” in New Letters identifies Salinger with transparent asperity as “the well-known recluse.” This is true and not true; it is, I suppose, what Ray means by “quirks,” an intolerantly simple label for a situation of some melancholy complexity.

Salinger has never been accessible. Fame overtook him in 1951 with the publication of Catcher, his only novel, and he fled attention just as the frail in health flee the winter cold. Generations of publicists for Little Brown, which still has all four of his books in print, never met him; never even talked to him on the phone. Mary Metcalfe, who was there in the ’50s, recalls, “I remember only that no one was to be in touch with him for any reason.”

J. Randall Williams, who managed the New York office of the Boston house and is now retired, was allowed to maintain some contact—by telephone and mail only—to deal with the physical details of bringing out the books. “A very particular man” was Salinger, exceptionally fussy about type faces and the quality of paper and design. For the green and white jacket of Franny and Zooey, published in 1961, Williams thinks he sent out twenty-seven samples of white before the precise shade was found to suit Salinger.

Catcher remains the undying favorite of the young. The Bantam edition, with more than six million copies in print, still sells well over 200,000 a year. There is somewhat less interest in Franny, Nine Stories and the volume containing “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” and “Seymour—An Introduction,” but they sell enough to warrant keeping them in print.

In public schools, Catcher is the second most popular fiction title after Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. Twenty-eight years after publication, it remains the most censored book on school lists, drawing regular objections, mostly from adults who have never read it.

Among the youngsters who do, most of them still succumb to Holden Caulfield, his rebellion, romanticism, wide capacity for love, and extravagant humor. The most ardent Salingerites also come to share Salinger’s infatuation with Franny and Zooey and the saintly suicide, Seymour.

A few of them grow into writers and teachers who take their love on a pilgrimage to Cornish, New Hampshire, where it is not welcome. Salinger has lived there for years, across the river from Windsor, Vermont, in a house as hard to find as a gas station on a rainy Sunday night. Divorced, he has a daughter and son who are young adults and visit regularly. He also has the uninvited callers who have inherited Caulfield’s talent for vivid fantasy. Each imagines Salinger will surely want to talk to him. Where the search for Salinger is successful, the encounter is either brief and inhospitable or brief and distantly polite. It is never informative. And no published report neglects to remind us that he is a recluse.

Yet if Salinger is walled in against the world, he does not precisely conform to the conventional image of the hermit. He manages to find his way out of the house to collect his mail, do his marketing, buy newspapers and books, and even see people he wants to see.

Last June, he traveled to Long Island to a restaurant where 500 policemen had gathered for a party for a retiring colleague, John L. Keenan, chief of detectives for New York City. Keenan and Salinger had been army buddies; they fought together in Europe in World War II, and their friendship had survived the return to civilian life.

In that boisterous, beery crowd, Salinger, the so-called recluse, seemed to have a fine time. After dinner, he made a speech in praise of Keenan; it was graceful, witty, effortless. Keenan, who now heads the security force at Aqueduct Race Track in Jamaica, New York, is uncomfortable discussing Salinger because he knows Salinger doesn’t like it and because he does not understand published accounts that depict his friend as an eccentric. The Salinger that Keenan has known for more than three decades is “very normal. He’s a kind, sensitive man, a good person to be with, with a good sense of humor. Everything I know about him is good.”

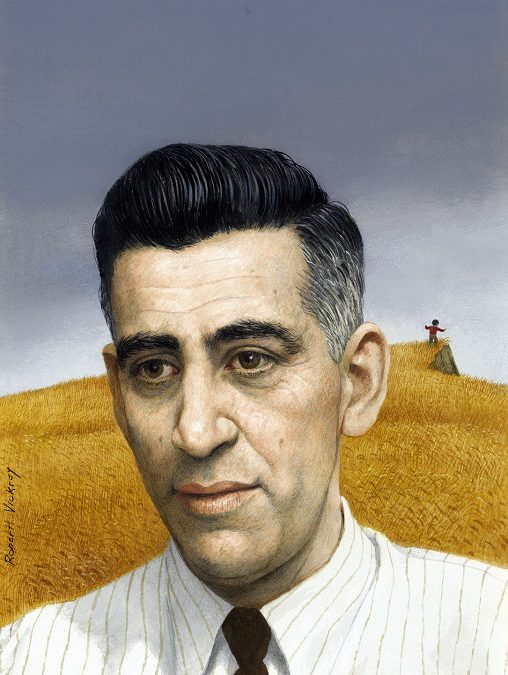

During the Keenan festivities, a friend of mine, a newspaperman who identified himself by name and trade, had a half-hour talk with Salinger. My friend recalls that he was dressed in well-made tweeds and that he was tall, slightly stooped, gaunt, extremely pale, and entirely gray—a time-eroded image of the luminously dark-eyed young man who allowed his photograph to appear on the jacket of Catcher for two editions.

Amiable but guarded, Salinger talked mostly about Keenan and the Keenan family, for whom he has great affection. The conversation was quiet, low-key. My friend does not know whether it was something Salinger said or something his manner conveyed; he remembers simply that he came away with the odd impression that he had just talked to a man who is “scared to death of not-nice people.”

The category would appear to embrace an assortment of types who represent peril to a defense system not quite as sturdy as a cobweb. It would include the critic, journalist, scholar and publisher, not to mention “the general reader,” who earns passing reference in “Seymour” as “my old fair-weather friend.”

The later fiction is strewn with sardonic commentary on the commentators: “a real artist… will survive anything (even praise).” “I’m told—critics tell us everything—that I have many surface charms as a writer.” “From the time Seymour was ten years old, every summa-cum-laude Thinker and intellectual men’s room attendant was having a go at him.”

As for publishers, to all appearances, Salinger no longer has one. His editor, Ned Bradford, the class act at Little Brown (Norman Mailer, John Fowles, the Henry Kissinger memoirs}, reports with uncharacteristic testiness that Salinger is a subject he prefers to forget. “He got mad at us when Time Inc. bought us out,” Bradford said.

According to one source, Time’s 1968 acquisition upset Salinger because he takes the general view that big corporations gobbling up publishing houses are acts inimical to the interests of writers. Also, he hates Time. There were some business differences with Little Brown after the takeover. A few years later he gave back the advance he had received for a volume that was to have included “Hapworth 16, 1924,” plus a companion story that never appeared.

“Hapworth” ran in the New Yorker on June 19, 1965, an issue that immediately became a collector’s item. Another episode in the Glass family saga, it was a 28,000-word letter from camp by the precocious, polysyllabic Seymour at the age of seven. The piece excited a good deal of media attention, much of it sour. It was Salinger’s last story to appear in print.

Rumor abounds that he is written out. In this context, it is useful to remember the assessment offered by the adult Seymour in an earlier story. Addressing Buddy, the narrator of the Glass stories who is assumed to be Salinger’s alter ego, Seymour asks, “When was writing ever your profession? It has never been anything but your religion.”

Five years ago, in a rare telephone interview, Salinger told a journalist that his stories no longer appeared because “publishing is a terrible invasion of my privacy.” Surely he referred not to the act of offering up fiction on the altar of literature, but to the commentary that any new Salinger story inevitably inspires. “Go to Europe,” a friend urges him, “so you won’t have to read about yourself.”

But he won’t or he can’t. He stays home and apparently writes steadily, halted mainly by the discovery that someone else has been writing about him. When that happens, one source reports. “it throws him off his work for a year.”

It is more likely a matter of days or weeks, but there is hardly any doubt that public commentary about Salinger induces a degree of distress or anger or anxiety that seems well-nigh phobic. It doesn’t matter much whether the judgments are sound or threadbare, nice or nasty. He can’t stand any of it.

And he can’t control it. What he can control is the flow of finished manuscript—stories no one else reads, not even his agent. So he dwells on his hilltop in flight from his audiences, suggesting nothing so much as a fine musician singing to silent rooms with empty chairs.

[Illustration by Robert Vickrey]