“And then they say, ‘Now, ladies and gentlemen, here’s the star of our show,’ and we both come out and go for the microphone, and you grab it and start right in, ‘Good evening, folks, it’s so great to be here in Miami,’ and I say, ‘Wait a minute, what are you doing out here? I’m supposed to be on first, I’m supposed to open the show,’ and you say, ‘No, they told me I was supposed to open the show,’ and we go back and forth like that until you say—no, I say—‘Look, didn’t you see the sign when you came up to the hotel? Didn’t you see that name up there with all the neon lights? Well, that’s me.’ And then you look and take a beat and say, ‘Oh, you must be Air Conditioning.’ ”

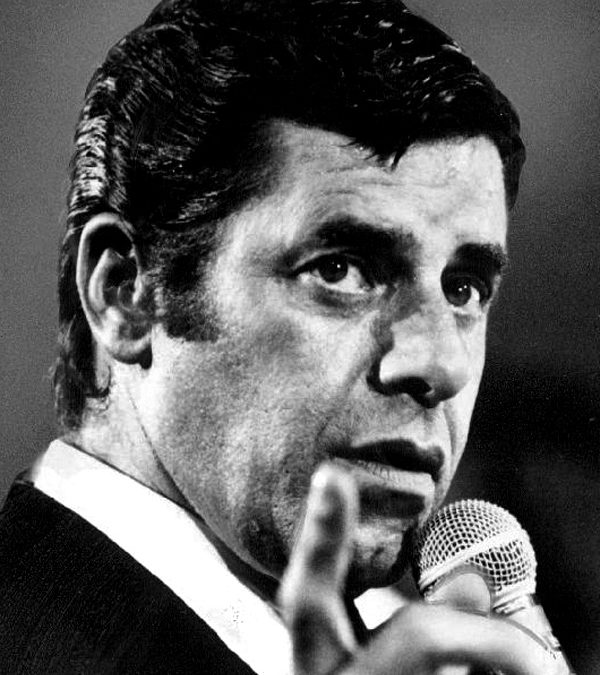

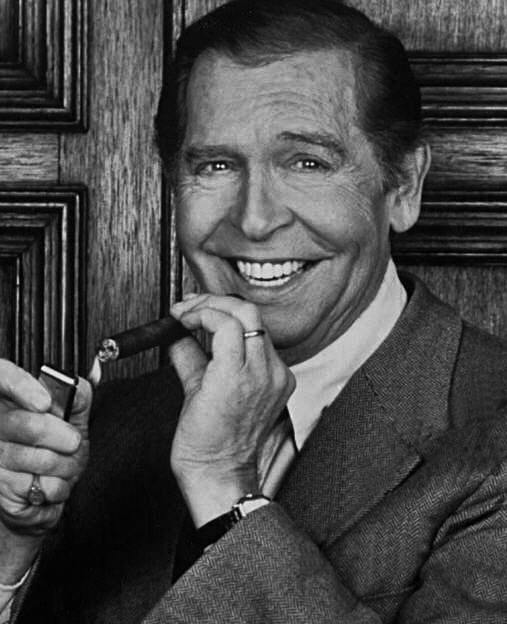

Milton Berle stopped to light his cigar. “You have to be sure to take that beat, Jerry,” he said. “Then you say, ‘Oh, you must be Air Conditioning.’ ”

Jerry Lewis looked at Berle but said nothing. He stood in his narrow dressing room backstage at the Deauville Hotel, dressed in a tuxedo, holding a plastic cup of white wine in one hand and a cigarette in the other. He took a sip of the wine.

“So then I’ll say, ‘Look, Jerry, why should you be on first?’ And you say, ‘Well, you heard me last night,’ and I say, ‘Yeah, you were very funny,’ and you say, ‘Funny? Are you kidding—you could hear them laughing across the street.’ I say, ‘Oh, really? What was playing over there?’ ”

Berle puffed on his cigar, then reached out and grabbed Lewis by the arm. “Listen, Jerry, I have to tell you about the ending.” Lewis dropped his eyes quickly to where Berle held him, then raised them again.

“When I finally introduce you,” Berle said, “you start in telling some story, right? And I back up a couple of steps and say, ‘Listen to this, this is a terrific story, you’ll love it,’ and you turn around and say, ‘Would you mind? Could you just back off?’ I say, ‘Sure, Jerry,’ and I go a couple of more steps, and as soon as you start again, I turn to the band and say, ‘This kills me, this story; wait’ll you hear it.’ And you say, ‘Look, would you just back away, I’m trying to do a show here. Back off.’ Then I walk up and say, ‘How far do you want me to go?’ And you say, ‘Have you got a car?’”

Berle tightened his grip on Lewis’ arm and pulled himself toward him. “Now, you can’t jump on that line, Jerry. You got to give it some time. When I say, ‘How far do you want me to go?’ you have to look at me and take a beat before you answer. Then you deliver the line. It’s funnier that way. Last time,” he said, “you rushed that line.”

Lewis still said nothing, but he gave his arm a slight twist and pulled loose from Berle’s hand.

“I think we got it all set, Jerry,” Berle said, heading toward the door. “Just remember the pause. These people need time to think down here.”

Berle started out of the room, then turned and looked at Lewis. “‘How far do you want me to go?’ he said. Then he paused dramatically and counted three beats in the air with his cigar. “And then you say, ‘Have you got a car?’” He put the cigar back in his mouth and walked out the door.

Lewis stood and watched him leave. Then he walked over to his dressing table and dumped the rest of his wine into the sink. He filled the plastic cup with water and used it to put out his cigarette. The cigarette hissed and then floated on the water like a dead fish.

Lewis shook his head and looked over at his wife, Patti, who was sitting in a corner of the dressing room, doing some needlepoint.

“He didn’t let you say a word, Daddy,” Mrs. Lewis said, looking up at her husband. “I don’t believe it. Milton came in here and did the whole opening routine and he didn’t even let you speak.”

“I don’t have to speak,” Lewis said. He sat down in a high-backed chair and shut his eyes. “Milton does all the parts. He even does audience reaction.”

Lewis opened his eyes and leaned forward to look at himself in the lighted mirror. He turned his head slightly to one side and then to the other. Under a layer of make-up, his skin was deeply tanned; and although his face had become fuller and more mature-looking with time, it had also retained a good deal of youthfulness. Jerry Lewis did not look his age, today, on his 47th birthday.

“Rehearsing,” Lewis said, patting back his hair. “That’s all Milton has on his mind. We’ve gone over that routine a million times since yesterday. And it’s just an opening bit, for Crissake.”

“I don’t see why Milton behaves that way,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“Well, Milton is the master of his craft,” said Lewis. “Everybody learned from him. He’s a perfectionist and a consummate showman. And for that I love him.” Lewis closed his eyes again and rubbed them. “But he’s driving me fucking bananas with all his rehearsing.”

“I think he goes a little too far, Daddy.”

“You could walk up to him and say, ‘Good morning, Milton,’ and he’d give you three other ways to read the line. On the way to his funeral, he’s going to be telling the guy how to drive the fucking hearse.”

Lewis stood up and began to look through a pile of mail that was sitting on his dressing table. He picked up a telegram from Bill Harrah, the nightclub owner, wishing him a happy birthday, and held it as if he were weighing it.

“We were wrong to come here,” Lewis said. “The place is wrong. I don’t belong in Miami.”

“I know,” said Mrs. Lewis.

“Jesus Christ,” said Lewis suddenly, throwing the telegram back on the table. “Milton’s coming in here and telling me how to deliver my fucking lines. I wrote the whole fucking routine, I should know how to deliver the lines.”

“Milton shouldn’t act like that,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“And he’s explaining to me about timing. He’s telling me about timing.” Lewis looked in the mirror. “I’m forty-seven years old today. I don’t need lessons in timing.”

“Of course you don’t,” Mrs. Lewis said.

A tall man with a mustache, who was the announcer for the show, stopped in the doorway and stuck his head into the room. “Are you just about ready, Mr. Lewis?” he asked.

Lewis nodded without turning around. He straightened his jacket and his tie. Then he leaned over and kissed his wife. “Good luck, Daddy,” she said to him.

“You know that Milton has always been my idol,” Lewis said as he stepped out of the room. “But I think he’s turning into a prick.”

Mrs. Lewis watched her husband as he left to go onstage; then she went back to her needlepoint.

The day before his 47th birthday, Jerry Lewis stood in the lobby of the Deauville Hotel, looking out through an enormous picture window at the swimming pool area. “Momma!” he said. “Come here and look at this! Look at this ping-pong table!”

Mrs. Lewis, wearing a summery pants suit and sunglasses, went over and stood next to her husband. “Look at what those people are playing on,” he said.

Lewis pointed through the window. Beyond it lay a huge swimming pool that nobody was using. The pool was flanked on two sides by narrow cabanas, most of which were open, occupied by post-middle-aged people sipping drinks and avoiding the hot afternoon sun. A number of other people were sitting out in the open, on deck chairs, some with silver reflectors strapped around their necks, and their heads thrown back like astronauts’ on take-off.

In an area directly beneath the picture window, a man and his wife were playing an energetic, if somewhat unpolished, game of ping-pong. Both wore broad-brimmed straw hats, and most of their efforts were directed at retrieving the ball after a missed return. The table they were playing on, the only ping-pong table in sight, was a warped piece of plywood painted green, nailed onto two sawhorses. The adhesive tape that had been applied to mark off the playing surfaces was fluttering lightly at the edges.

“Can you believe that?” Lewis asked, his eyes fixed on the table. “People here are paying a hundred, a hundred and fifty dollars a day for a room, and look at that piece of shit they provide in the way of recreational facilities. That is absolutely unexcusable.” He turned away from the window. “Welcome to Miami,” he said.

It was about noon and Lewis had just arrived at the Deauville to rehearse for the opening of his show that night. He had come from The Jockey Club, where he was staying, a 25-minute ride by chauffeur-driven limousine across the bay from Miami Beach.

“Let’s find out where we’re supposed to go and go there,” Lewis said. He started off across the lobby, followed by his wife and by his assistant, a man named Bob Harvey.

“Look at the carpeting!” Lewis called out as he walked along. “Holes in the carpeting!” He stopped above one of the holes and examined it. Two silver-haired ladies sitting nearby looked on with interest.

“Now, it would be one thing,” Lewis said, “if they said that the carpeting had been torn in the last fifteen minutes and they just hadn’t gotten around to fixing it yet. But those holes have been there since Lindbergh landed in Paris.”

“This used to be such a groovy hotel,” Harvey said, catching up to Lewis.

“This was the best,” said Lewis. “This was class. Now take a look.”

“The Fifties was the best time for Miami,” Harvey said. “The late Fifties.”

“The town was alive then,” Lewis said. “The people were alive. Now everyone in sight is on his way to fucking death.” He looked around at the silver-haired ladies and lowered his voice. “It makes you sad to see a town deteriorate like this.”

Mrs. Lewis came up and joined them. “Did you see the carpet, Momma?” Lewis asked. Mrs. Lewis looked at the carpet and shook her head.

Lewis led them toward the stage-door entrance. Harvey asked him if he’d seen the room in which he was performing. Lewis shook his head. “It’s big, Jerry,” he said.

They went through the door and into the room. “Holy Christ!” said Lewis, looking around. “Is this where the Dolphins play their home games?”

“Why, it’s like a convention hall,” said Mrs. Lewis, laughing. “They could hold a convention in here, Daddy.”

“They must be out of their minds,” Lewis said. “They’re never going to fill this place every night. There aren’t that many people in Florida.”

A number of people were moving unhurriedly around the room, setting up the lighting and sound equipment. Onstage, the band was being led through the numbers in Lewis’ act by his accompanist and conductor, Lou Brown, a full-faced and pleasant man who has been with Lewis for 23 years.

“Some room they got here, huh?” Brown said as Lewis walked over to the edge of the stage.

“Nice,” said Lewis. “Especially if you want to fly an airplane.”

“Maybe that’s what the show needs,” Brown said.

Lewis smiled and took some notes out of a briefcase. He glanced through them, then stood listening to the band. “When do you need me, Louie?” he said.

“Not right away, Brown said. “We’ll go through it all first. Then you can come in and tell us how we did it all wrong.”

Lewis and his wife came out of the Deauville together and alone and walked over to the car that was waiting for them. The night air was misty and muggy. The neon time-and-temperature board on the delicatessen across the street said that it was 72 degrees, a few minutes before midnight.

Lewis was wearing the tuxedo that he had performed in, except for the jacket. He had left the jacket backstage. He had on a dark-blue nylon windbreaker zipped up to the throat and a white bath towel wrapped around his neck. His make-up was smeared and running from the perspiration that dripped from his hair and his forehead, and both the collar of his shirt and the bath towel were stained with the tan-colored grease.

He slumped into the seat and put his head back, his eyes shut. The driver turned around and gave him a questioning look. Mrs. Lewis made a small motion with her hand and the car pulled away from the hotel.

“There won’t be any sleeping tonight,” Lewis said in a tired voice. “I have to look for some answers. There have to be some answers.”

“What did Milton have to say?” Mrs. Lewis said.

“Milton was very understanding,” Lewis said. “He said to me, ‘What can we do?’ He told me that he knows he went way too long. I said, ‘Milton, that’s only a small part of it.’ The thing about chemistry is that there are particles, and pieces, and small factions that build into the totality of the end result. Timing is just one thing.”

Lewis took the corner of the bath towel and wiped some of the sweat off the side of his face.

“You can’t plan a concept,” he said, “and then change it, and expect it to work after you’ve made the change. When we originally planned to do this, it was going to be Milton and myself and the Louis Prima outfit—and we were going to work in concert and build a kind of revue. Then Prima became unavailable. And then Lee Guber, who put the show together, said that it would just be Milton and myself, and that it would work just as well that way, with each of us doing about an hour. And I really had some reservations about that. But I knew how important it was to Milton, I knew how much he was looking forward to us working together, and so I really didn’t put up any resistance to the show’s changing from the original concept. Because I didn’t want to make waves.

“But you know I talked to Milton, months ago, and I kept trying to make him understand that there had to be a device to take the place of the original concept. And then I just ran out of time. I left the country, and then my dad got sick, so we never did get together. And even if we had gotten together, it would have been a very amateurish thing for us to attempt to work in total concert. Here you have two men who shouldn’t really be working together at all, trying to weave their two styles and two acts together in some way. Anyhow, we never did work anything like that out, because there was just no time.”

“Daddy, can I interrupt a minute?” Mrs. Lewis said.

“What?”

“I don’t think you ought to have this air conditioning on. I think it’s too much air for you, darling. It’s so cold on your neck.”

Lewis asked the driver to turn off the air conditioning in the back of the car.

“Thank you, Phil,” Mrs. Lewis said to the driver. “He’s still all wet and it gets too cold for him.”

They drove in silence for a while, and then Lewis said, “It’s really a strange thing. I was so confident tonight, for some reason. I had heard how the audience reacted to Milton during that whole first half, and I said, ‘Jesus Christ, they’re up, they’re high.’ And when I walked out, I walked out just like I did in Paris. Very secure and very confident. And the minute I began, I knew I was in trouble. That it wasn’t going to work. They’re different people. It’s a different place and a different audience, and I just—I’m not right here.”

Lewis shifted in the seat and rested one foot on top of the seat in front of him.

“They just didn’t understand some of the things that you were doing,” Mrs. Lewis said. “You were too subtle for them. Too quick.”

“Well, you can’t do subtleties and artistic pieces with this audience,” Lewis said. “They aren’t used to that kind of comedy or that type of sophisticated performance, the way they are in Europe. Or even the way they are in Las Vegas.”

“You did pieces tonight that would get a five-minute laugh in Las Vegas,” Mrs. Lewis said. “And here they didn’t respond at all.”

“Well, this isn’t Vegas,” Lewis said. “This is Miami, and I haven’t been in Miami in a long time. They haven’t seen my style of performance in a long time. In a sense, they didn’t recognize me.”

The car bumped slightly as it pulled onto the causeway and headed across the bay. Behind it, the carnival lights of Miami Beach were dim and fuzzy in the gray mist, as if the city had been wrapped in wax paper.

“You looked so gorgeous up there,” Mrs. Lewis said, smiling at her husband. “So polished and so—well—really performing. Milton wasn’t really performing.”

“Oh, yes, he was, Momma,” Lewis said.

“Oh, not to me, it’s not a performance,” Mrs. Lewis said. “He just works around the other people he has on with him. Like that harmonica player, that Stan Fisher. He plays beautifully and I really enjoy the music, but it was too much and too loud. It’s a drag. You come to see Milton Berle and you see a harmonica player.”

“Well, I don’t know how long that went,” Lewis said.

“He had an awful lot of time, Daddy. Much too much.”

“Yeah, Stan might be on too long,” Lewis said. “But you can’t say Milton wasn’t performing, honey.”

“No,” Mrs. Lewis said. “To me, that’s not a performance. I’m sorry, it’s something else. I don’t know what you’d call it.”

“You might call it prejudice,” Lewis said.

“No, that’s not it.”

“You know better than making it a contest,” Lewis said. “I’m not making it a contest, and I’m not saying I didn’t enjoy it. I enjoyed Milton. But he was too loose. He wasn’t organized. He looked—he looked like he was floundering all over the place. Compared to what I see you do.”

Mrs. Lewis reached over and began to rub her husband’s neck lightly.

“I knew what the outcome was going to be,” Lewis said. “I had a feeling it was going to happen this way. I told you that last night.”

“Yes, you told me,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“I could just feel that the chemistry was wrong,” Lewis said.

“Maybe it would be better if you opened the show,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“Well, I told Milton that I’d be prepared to do anything at all to make it work; and maybe that means me performing first. But I don’t even know if that’s right. I think the problem is much more fundamental.”

The car turned onto Biscayne Boulevard and headed north. There were no other cars and no other people, and the small single-story houses that were set back on either side of the wide street were quiet and dark.

The limousine turned into the entrance of The Jockey Club and a uniformed guard stepped out of his booth.

“Mr. Lewis,” the driver said.

The guard bent over slightly and looked in the back window at Lewis and his wife. “OK,” he said and waved them on.

“Phil, what time is it?” Mrs. Lewis said as they drove through the gate.

The driver looked at the clock on the dashboard.

“Almost twelve-thirty, Mrs. Lewis,” he said.

“Oh, Daddy,” she said. “It’s your birthday already.”

Mrs. Lewis put her arm around her husband’s shoulders and gave him a kiss. “Happy birthday,” she said.

“Happy birthday, Jerry,” Jan Murray said. He poured some wine into the glass Lewis held in his hand.

“Here’s hoping for many more.”

Murray’s wife, a beautiful woman named Toni, held up her own glass in a toasting gesture. “Happy birthday, Jerry,” she said. “We all love you.”

Mrs. Lewis laughed and applauded lightly. “Hooray for the birthday boy,” she said.

The four of them sat in Lewis’ small backstage dressing trailer. Lewis, who had just finished performing, had his tuxedo shirt pulled out of his trousers and unbuttoned down to the middle of his chest. It was splotched with perspiration.

Onstage, Berle was beginning the second half of the show.

“I heard these two ladies talking in the lobby during the intermission,” Berle said, peering out at the audience. “And one lady says to the other, ‘Sex gives me a pain in the neck.’ The other lady says, ‘Well, maybe your husband is doing it wrong.’ ”

The audience roared and Murray pointed in their direction with the bottle of wine. “Good group,” he said.

“Not bad,” Lewis said. “Better than last night.”

Nobody said anything for a moment, and then Mrs. Murray said, “You look marvelous, Jerry. You keep having birthdays, but you don’t look any older.”

“Fucking middle age,” Murray said, taking a drink from his glass. “I never thought I’d see it. I tell you, Jerry, I never thought of getting old.”

“Oh, you’re not old, Jan,” Mrs. Lewis said. “If you’re old, then we’re all old.”

“I don’t mean old old,” Murray said. “But you begin to get these reminders that you aren’t as young as you used to be. Particularly on this fucking condominium route.” He took a drink. “But the people are beautiful, Jerry. That I gotta say. They’re so warm and receptive. They just smother you with affection.”

“You should have seen the reception we got in South Africa,” Lewis said. He took the bottle of wine from Murray and poured some into his glass. “Talk about warmth. I’ve never seen anything like it in my life. See, they don’t have any TV in South Africa. None. So when I arrived—when the people heard that Jerry Lewis was going to perform in concert—Jesus Christ, you’d think that Frank Sinatra and the Pope showed up.”

“I hear their act is a little slow,” Murray said, drinking.

“Tell Jan about the welcome,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“We land at the airport,” Lewis said, “and we look out the windows of the plane, and the airport is covered with South Africans, with Zulus, and they’re all chanting and yelling.”

“And you thought they were out to shrink your fucking head,” Murray said.

“It was a ceremonial welcome, Jan,” Lewis said. “They were of all ages. There were kids in wheelchairs. Jesus Christ, I never saw so many people. And they performed this Zulu welcome just for us.”

“Tell him about the drive into the city,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“It’s eight miles from the airport to the city,” Lewis said. “And when we drove in, there were Zulus lining both sides of the road for the entire eight miles, cheering and shouting. And they have a whole series of bridges that you pass under on the way. Every one of those bridges had a huge placard hanging from it, saying, ‘Welcome, Jerry Lewis.’ ”

Lewis smiled and then shook his head. “I have that welcome on tape,” he said. “It was really something.”

“Nothing like that would happen here.”

They were all quiet again, and then Murray said, “Are you going back home when you finish here, Jerry?”

“No,” Lewis said. “I’m going to Germany.”

“You’re going to Germany?”

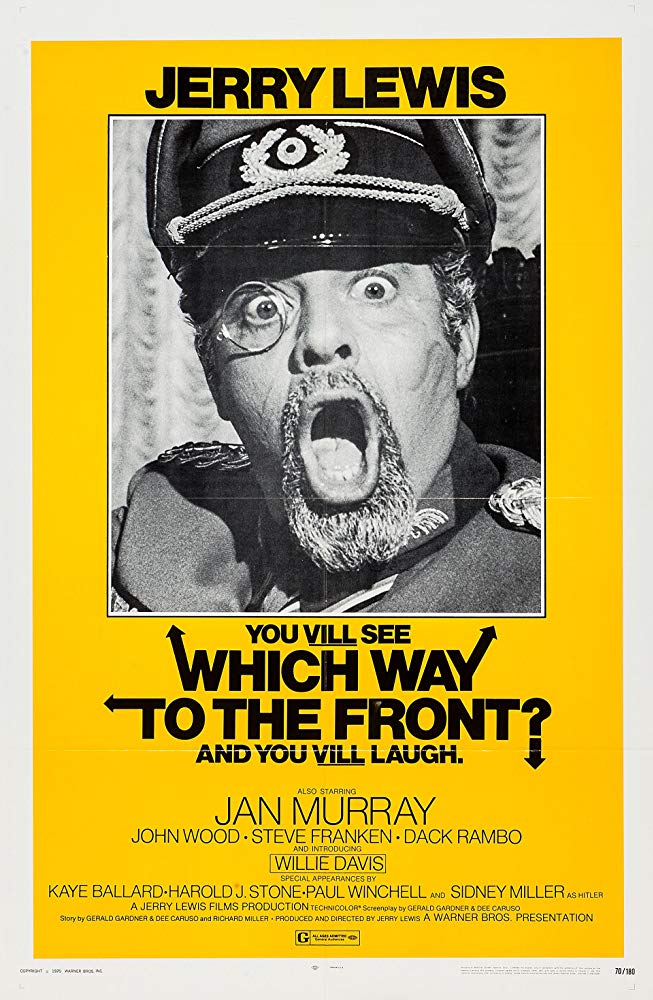

“The war is over,” Lewis said, smiling. “I’m going to do a show for German TV and I’m going to give a one-man concert. I’m also being given a German film festival award. He pointed at Murray. For our picture.”

“For Which Way to the Front”? Murray said. “You’re pulling my fucking leg.”

“No,” Lewis said, shaking his head. “That picture played sixteen first-run weeks in Berlin. With lines down the block.”

“That’s unbelievable,” Murray said. “It’s an anti-German film.”

Lewis shrugged. “The Europeans think differently about things. They explore and accept film as art. It’s a completely different attitude from the way films are viewed here.” He finished the wine that was in his glass. Anyway, the picture was named best picture of the year, from anywhere, and I was named best director. It’s my ninth foreign film award.”

“That’s wonderful, Jerry,” Mrs. Murray said.

“It’s fucking ironic,” Murray said, laughing. “That’s what it is. Imagine going from Miami Beach to Germany.”

“I’m counting the days,” Lewis said. “Which reminds me—”

He took a felt-tip pen from the dressing table and began to write on the mirror. He wrote the names of ten days, starting with Thursday, the day before, and ending with the Saturday after next, the night he was scheduled to close. He crossed off the first two days and put the cap back on the pen.

“Two down and eight to go,” Lewis said, stepping back from the mirror and looking at what he’d written. Everybody looked at the mirror expectantly, as if it were going to speak.

“Miami’s a toilet,” Lewis said finally. “The best thing you can do for it is to pull the chain.”

Then, brightening suddenly, Lewis said, “Hey, this is supposed to be a birthday. Where’s the fucking cake?”

Lewis stood in the mirrored lobby and waited for the elevator. A lady leaning over the reception desk called to him from across the room.

“How’s your father doing, Jerry?” she said. “Is he feeling better?”

Lewis turned and looked at her briefly. “He’s much better, thank you,” he said.

“We all wish him well,” the lady said as Lewis stepped into the elevator.

The elevator gave a lurch and then started up. Lewis looked sideways and caught his reflection in the smoked glass, then looked away.

The corridor was narrow and dark. It had a low ceiling spotted with dim-wattage light bulbs. The apartment doors all had brass-colored doorbell units planted on them like corsages and circular peepholes that stared at one another across the hallway.

Lewis walked all the way to the end of the hall and rang one of the bells. A short woman in a patterned blue house dress and slippers opened the door and put her arms around him. “Hello, Jerry!” she said, kissing him on the cheek. Lewis set down the briefcase he was carrying to give his mother a hug.

“Jerry’s here,” Mrs. Lewis said, taking him into the apartment. He followed her down a short entrance hall that led into a combination dining area and living room. The hall had a small table sticking out from the wall, with a gold-flecked mirror hanging above it. The mirror was ornamented with color snapshots wedged in between the frame and the glass.

The living room, which was not large, was dominated by a heavy metal hospital-style bed that was made up against one wall. This wall also had a thick fire door leading out to an open balcony that overlooked Collins Avenue, the main street at this end of Miami Beach. Across the boulevard, there was a coffee shop, with a sign flashing the words Open 24 Hours in colored lights.

“Hello, Pop,” Lewis said. He crossed the room and kissed his father, who was sitting in a wheelchair not far from the metal bed. “How’ve you been doing?”

Danny Lewis held his son’s hand and smiled at him faintly. He was a painfully weak-looking man, whose body and face had been shrunken by a series of violent strokes. Behind him, on the wall, there was a photograph taken a couple of years before, showing him as a robust, full-faced man, with a broad and winning smile and a full head of hair. Now his hair was thin; his face was stretched and gaunt; and yet his eyes, just as the eyes that looked out brightly from the photograph on the wall, were keenly alive.

“Danny’s been doing just fine,” said a short, plump lady sitting on one of the chairs in the dining area. “How have you been, Jerry?”

“Oh, Christ, Aunt Jean, are you still here?” Lewis said, turning in her direction. “Ma, I thought you told me Aunt Jean was leaving today for sure.”

“Now, what kind of way is that for you to talk to your aunt?” Aunt Jean said from her seat.

“He shows no respect, this boy,’” Mrs. Lewis said with a laugh. She patted him on the cheek. “Sit, Jerry. Sit down and be comfortable.”

She left the room and Lewis took a seat on the sofa, on the opposite side of the room from his father.

“Have you been behaving yourself, Pop?” Lewis said. He turned his head and looked at his father’s nurse, a young and pretty black girl, sitting at the other end of the couch, watching Mike Douglas on television.

“Has he been doing what he’s told?” Lewis said to the girl.

The nurse smiled across the room at Danny Lewis. “He’s been pretty good,” she said. “He doesn’t give me too much trouble.”

Mrs. Lewis came out of the kitchen holding a glass jar. “Let me fix you something to eat, Jerry,” she said. “Try some of this.”

“What, I’m here two seconds and you’re feeding me already,” Lewis said. “I don’t need anything to eat.”

“I bet you haven’t eaten anything today,” Mrs. Lewis said. “You never eat properly. Here,” she handed him the jar, “this is marvelous.”

Lewis held the jar and looked at it. “What is it?” he said.

“Herring,” his mother said. “Delicious.”

“And I eat it right out of the jar?” Lewis said.

“No, dear, you eat it on a plate,” his mother said. “I’ll fix it up for you. I’ll bring you some Ritz crackers with it.”

Lewis settled back on the couch as his mother went into the kitchen.

“So when are you leaving, Aunt Jean?” he said, looking at his watch. “You going back to California soon?”

“Fresh boy,” Aunt Jean said, polishing her glasses on the front of her dress. “How’s your show going, fresh boy?”

“Show’s OK,” Lewis said. “Milton’s rehearsing me every time I turn around, but other than that, OK.”

“How is Milton?” Aunt Jean said.

“Milton is Milton,” Lewis said. He looked at his father and said, “He wanted to be remembered to you. He said to be sure to give you his best. I think we’ll come up someday and see you. After he gets through restaging my whole act.”

Mrs. Lewis came in with a plate full of food and set it down on the coffee table. Lewis leaned forward, took a fork off the plate and began to eat.

“What is this stuff I’m eating, anyway?”

“Herring tidbits,” Aunt Jean said. “Spiced.”

“Delicious,” Mrs. Lewis said from the kitchen.

“Jew food,” Lewis said, wiping his mouth with a napkin. “This stuff killed more of my people than Hitler.”

“No, everybody likes that,” Aunt Jean said. “Scandinavians and everybody. In Sweden they make salads with herring. I have the recipes.”

“In Sweden you pay nineteen dollars for a portion of smoked salmon,” Lewis said.

“Oh, my God,” Aunt Jean said. “Who wants to eat that?”

“When you taste it, you do,” Lewis said.

“Are we going to eat lunch?” Lewis’ father said. His voice was hoarse and strained.

“You had lunch, and you had breakfast,” Aunt Jean said, her voice raised. She looked at him over her glasses.

Danny Lewis stopped, as if to think about what she said. “What did I have?”

“You had fish,” Aunt Jean said emphatically. “You had that lovely fish that I bought.”

“Fish and carrots,” the nurse said.

“And mashed potatoes,” Aunt Jean said.

“And I had that today?” Danny Lewis said.

“You had that for lunch,” Aunt Jean said. “Why don’t you walk a little bit. Danny? You aren’t walking enough.”

The nurse went over and helped him out of the wheelchair, then held his arm and guided him into a metal walker. He began to move slowly across the room.

“Hey,“ Aunt Jean said, looking over at the television, “there’s Joe Namath. Everybody makes such a big fuss over him. Do you know Joe Namath, Jerry?”

“Sure,” Lewis said.

“What’s so wonderful about him?” Aunt Jean said.

“He’s a marvelous guy,” Lewis said.

“He looks like a nice boy,” Mrs. Lewis said. “He’s got a cute impish smile. I think he’s impish-looking.”

“We don’t have anything with Muscular Dystrophy that Joe Namath isn’t there to help,” Lewis said.

“A dimple in the chin, the Devil within,” Aunt Jean said.

Lewis got up and opened the briefcase that he had brought with him. He took out a cassette recorder and began to rewind the tape.

“I think he’s going to put you down on tape,” Mrs. Lewis said to Aunt Jean.

“Oh, I’ll kill him if he does,” Aunt Jean said. “I’ll kill you if you do, Jerry.”

“You know you can’t trust him when he carries his valises,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“I don’t know what he carries in his valises,” Aunt Jean said. “Maybe he’s carrying extras in there. Whatever that is.”

“You’re rambling, dear,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“So I’m rambling,” Aunt Jean said. “Don’t dare use that, Jerry.”

Mrs. Lewis looked over at her husband and said, “Give me a note, sweetheart.”

Danny Lewis sang a soft and raspy note.

“Couple of notes,” Mrs. Lewis said. “It’s good to use your voice.”

Danny Lewis sat and composed himself for a moment; then he began to sing: “‘It’s impossible … ask a baby not to cry, it’s just impossible….’ ”

“Perfect pitch,” Lewis said to his father, after he sang a few lines of the song. “What key was that?”

“Very low,” Mrs. Lewis said. “Maybe a C.”

“E-flat,” Danny Lewis said in a small voice.

“‘It’s impossible …’ ” Lewis began to sing in a high shrieking comic voice, “‘to see goyim in a synagogue, it’s just impossible….’ ”

“No it’s not, not anymore it isn’t,” Aunt Jean broke in.

Lewis gave his Aunt Jean a look and his mother began to laugh loudly. Lewis punched the Record button on the cassette machine.

‘“Honey,” Mrs. Lewis said to her husband, “give me a real nice note, now. Do My Way.”

Danny Lewis did not answer; he sat looking down at his hands, which were folded in his lap.

“Give him the opening words,” Aunt Jean said.

“‘And now….’ ” Mrs. Lewis began.

Danny Lewis sat still for another moment, then began: “‘And now … the end is near … and so I face the final curtain….’ ”

As his father began the song, Lewis turned his eyes away and lowered them to the floor.

“‘My friend … I’ll say it clear … I’ll state my case, of which I’m certain….’”

When he came to the end of the song, there was a pause in the room. Then Lewis said, “You hit some pretty high notes there, Dad.”

“Did he ever!” Mrs. Lewis said. “Oh, did he go up high! It was beautiful, sweetheart.”

“Why don’t you sing a song with him, Jerry?” Aunt Jean said.

“Ah, why don’t you just butt out, Fat?” Lewis said. “Trying to run everything.”

“I don’t like you,” Aunt Jean said.

“I never liked you,” Lewis said. “I was stuck with you. They told me one day, ‘That’s your aunt. That’s a lamp, there’s the couch, that’s your aunt.’ I got rid of the lamp, I got rid of the couch and, Jesus Christ, you’re still around.”

“So the same thing happened with me when they told me you were my nephew,” Aunt Jean said. “So we’re stuck with each other.”

Lewis walked over to her and gave her a hug and a kiss on the cheek.

“Hey, tell me,” he said to his mother. “Incest with an aunt ain’t bad, is it?”

“Terrible,” his mother said, smiling at him from the couch. “The worst.”

When Lewis walked out of the building, the afternoon sunlight was beginning to fade and a bright stream of neon lights had come on up and down the boulevard.

He walked over to his car and got in the back seat. He sat without doing anything for a minute, then he took out his tape recorder and put it on his lap. He punched the Play button and the sound of his father’s voice, singing the lyrics to My Way, came from the speaker.

“Where to, Mr. Lewis?” the driver said, looking into the rearview mirror.

Lewis did not answer; he just sat listening to the tape recorder.

“You want to go over to the Deauville now?” the driver said. “It’s about five o’clock.”

“Yeah,” Lewis said finally, pushing the button to stop the tape. “Yeah, take me there. And then I want you to go someplace where they have fruit. Gift packages of fruit. I want you to get a basket filled with fruit, and some cheeses, maybe a bottle of booze, and I want you to bring it back to my parents. Get the biggest one they got. Spend fifty bucks or something.”

He took a bill out of his wallet and handed it across the front seat to the driver.

“I know just the spot,” Mr. Lewis, the driver said. “Real gourmet place. Very high-class.”

Lewis nodded and sat back in the seat. “They should have something nice up there in case company comes,” he said, rewinding the tape. “It doesn’t look good for people to come up and not see anything there.”

The driver started the limousine and nosed it out into the stream of traffic. Lewis was listening to the tape of his father’s voice once again as the car drove off down the street.

“Miami sucks!” Lewis shouted from the bedroom. He went over and put his head into the living room of his dressing suite in the Deauville. “Sucks!”

Harvey sat on the sofa, drinking coffee and eating poundcake with a fork. “Used to be groovy,” he said with his mouth full.

“Used to be, used to be,” Lewis said, walking back into the bedroom. “Now it sucks.”

He switched on the television and began to go through one of the dresser drawers. “The people here know from nothing. Nothing do they know. They know ‘shit’ and they know ‘fuck,’ and anything else is out of their league.”

He slammed the drawer shut and attacked another. “If you don’t open with ‘fuck,’ you bomb. ‘Hickory dickery dock, the mouse ran up the clock; fuck him, let him stay there.’ Then you’re a hit.”

He slammed the second drawer shut and reappeared in the doorway. “Do a routine that starts, ‘Two Jews fucked a sheep….’ and then you’re home free.”

He went back into the bedroom and looked at the television. It was showing a telethon that was being held in the Miami area to raise money for children’s diseases. It was being hosted by a local personality, a fat emcee with a leathery tan.

“And I want to make this plea from the bottom of my heart….” the fat emcee was saying.

“The bottom of your heart is in your ass, you local piece of Miami shit,” Lewis shouted at the television. “Fucking amateurs. Don’t know anything about putting on a fucking telethon. Might as well stay in the fucking bed, for all the money they’ll raise.”

He went into the living room and walked over to the bar. “You know what pisses me off most about this fucking place?”

Harvey did not answer, just sipped his coffee.

“It’s not that fucking stadium we’re playing in, with all the empty chairs,” Lewis said, pouring himself some wine, “and it’s not Milton with all his fucking rehearsing, and his shitkicking complaints and suggestions”—he drank the wine in a gulp—“but what really pisses me off about Miami is the fucking people. The fucking insensitivity of the people.”

“You shouldn’t let it get to you,” Harvey said. “They don’t know any better.”

“They should know better,” Lewis said, his voice rising. “They’re adults. I’m going to punch somebody in the mouth pretty soon.”

He poured another drink. “They come up and they grab you. They grab your fucking coat. Did you see that guy in the lobby today? Grabs my fucking arm and says, ‘Hey, stay here, Jerry, you gotta say hello to my wife.’ I gotta say hello to his wife? I told him to take his fucking hands off me.”

“There’re assholes everywhere,” Harvey said. “What are you going to do?”

“There’s no excuse for bad manners,’” Lewis said. “There’s no excuse for bad taste. They treat you just like an object. They act like you were the Statue of fucking Liberty. Well, I’m not going through that lobby again, that’s all. If I can’t get on without going through the fucking lobby, then I don’t go on. It’s Jew-a-Rama down there. Wall-to-wall Jews. He swallowed the rest of his wine. If I stay here much longer, I’m going to end up sending money to the Arabs.”

From the television set in the bedroom, the fat emcee said, “And the phone calls were just not coming in like they should while the Harrington Quartet was performing so beautifully….”

“They can’t call when they’re watching the talent, you fucking fruitcake,” Lewis yelled back. “They call after the Harrington fucking Quartet goes off. Jesus Christ Almighty!”

He poured another glass of wine, draining the bottle. He looked at the empty wine bottle a moment, then slammed it against the wall. “I christen this hotel ‘Motherfucker’!” he shouted. “Pull out the pilings, you sons of bitches!”

He disappeared into the bedroom and came back with a can of lighter fluid. “Here!” he called to Harvey. “Watch carefully.”

He poured some of the lighter fluid into a glass ashtray, struck a match and dropped it in. The ashtray went up in a burst of flame. “The Great Super Jew and His Burning Ashtray!” Lewis shouted. “Speak to me. Burning Ashtray!”

Harvey went over to the bar and put out the ashtray with a bottle of Coca-Cola. Lewis was in the bathroom pouring lighter fluid into the toilet. He tossed in a match and the bowl ignited.

“Keep your eyes on the fucking fire!” Lewis shouted. “Anyone who grabs the Super Jew’s coat will have to contend with my firepower!”

Harvey went into the bathroom and flushed the toilet. The flames disappeared like a drowning man.

“And now for the greatest feat of all!” Lewis yelled. He sprinkled the lighter fluid in a trail across the bathroom’s tile floor. He threw on a match and the bathroom lit up with a roar.

“Aha!” Lewis said, watching the flames. “That’s it, burn! Burn, you motherfucker! Burn down the fucking hotel! Burn down the whole fucking town!”

The German countryside appeared suddenly through the clouds, like a rabbit pulled out of a hat; misty, gray-green fields clumped with trees that tilted steeply under the wing of the 747 as it made its approach to Frankfurt’s Rhein-Main Airport.

The air on the ground was chilly and damp and beads of moisture splattered across the windows of the plane as it rumbled in a great arc toward the concrete-modern terminal building and came to a stop in the early-morning haze.

Lewis came off the plane wearing a short green topcoat and sunglasses. He was followed by the five members of his staff, all looking tired and rumpled.

They were met by an enthusiastic young man from the airline, a blond-haired German dressed in a navy blazer, who informed Lewis that there was a private jet waiting to fly them to Cologne, where Lewis was performing, but first he would take them upstairs to a lounge, where they could have some coffee.

They took an escalator to the upper level. The young man ushered them into a spacious and pleasantly furnished room.

“Well, now!” the young man beamed. “Shall we perhaps take a seat in here, or, if you would prefer, we can swing on into the leather room.” With a gesture, he indicated an adjoining room furnished with leather couches and an enormous bar, which, at 8:30 in the morning, was deserted.

The Lewis group looked at the young man with tired eyes. They swung on into the leather room.

A pretty, dark-haired girl in a blue uniform left a small desk across the room and went over to take orders for coffee and juice.

The young man from the airline approached Lewis and said that there was a reporter outside from one of the radio stations wondering whether Lewis could spare a few minutes for an interview. Lewis nodded wearily and removed his dark glasses.

The young man brought in the reporter, a massive, dominating man with a great beard. He shook hands formally with Lewis and began to unpack a tape recorder.

The dark-haired girl appeared with a tray. She served cups of coffee and glasses of tomato juice to several members of the group, then went for the rest of the order.

“No ass on that chick,” Lou Brown said, watching her walk away. “Nice legs, nice tits.” He sipped his tomato juice. “No ass.”

Harvey stirred his coffee and smiled across the room at the girl. She smiled back demurely. “So she’s shooting two for three,” he said. “And she hasn’t even suited up yet.”

The bearded reporter had started his machine and he squatted on his heels in front of Lewis, holding a microphone.

“Tell me, Mr. Lewis,” he said in perfect English, “what I would first like to ask you is whether you think of yourself as having a public face, as in your films, and another separate private face, which the public perhaps does not see.”

“Well,” Lewis began in a tired voice. “Well, I think that every performer, not just myself, projects a certain special image when he is functioning publicly, as an entertainer, or an actor. This image is an extension of that person’s total personality, although the public often sees only a single facet—”

He stopped as the dark-haired girl lowered a coffee cup in front of his face. He looked up at her and then back at the reporter.

“A single facet,” he said, then stopped. He rubbed his eyes and looked again at the girl.

“Cream?” she said politely.

Lewis looked from the girl to the man crouched in front of him, holding the microphone in expectation. Then he covered his face with his hand and began to laugh.

The reporter smiled uncertainly behind his thick beard, as if anxious to share in something he did not quite understand. After a few moments, with Lewis still laughing, the smile collapsed like a balloon losing air and the man pushed the stop button on the recorder.

“That was sensational, Jerry!” the director said, walking toward the front of the stage. He came through the wooden chairs and the music stands, and his image bounced onto the half-dozen monitors that were spotted around the subterranean television studio. He was a tall, handsome-looking German, with slightly graying hair.

“Where are you, Jerry?” he called out. “That was magnificent!”

Lewis, dressed in janitor’s blue overalls, came through a door and walked over to where the director was standing.

“Sensational, Jerry!” the director repeated. “And on the first take!”

“Yeah, I thought it went well,” Lewis said calmly. “Let’s look at it and see.”

The director called up to the control booth and asked for the tape to be played back. The members of the crew began to form groups in front of the monitors, waiting for Lewis’ performance as a janitor conducting an imaginary orchestra in an empty concert hall.

The monitors buzzed, and then Lewis, dressed in overalls and pushing a broom, came onto the screen. The people standing in the back of a group raised themselves up on their toes to get a better look.

The German television crew seemed to find the sketch hysterically funny. They laughed loudly and appreciatively all through the video-tape playback, picking up on every nuance of Lewis’ performance, and when it was over, they broke into a vigorous round of applause.

Lewis, who had watched himself on the monitor with his arms folded and no expression on his face, acknowledged the applause with a smile. Then he turned and looked at the director, who was standing next to him.

“Your timing is brilliant,” the director said admiringly. “Absolutely brilliant.”

Lewis nodded, and then he said, “What’s next?’

The reporters gathered in front of Lewis in a large group, holding yellow pencils and folded pieces of colored paper. Lewis sat facing them in a metal chair, with his cassette recorder resting on his lap, his tuxedo tie pulled loose and his shirt unbuttoned at the throat.

It was almost six o’clock in the evening and the taping of Lewis’ show had just ended. In the background, there was a hum of German voices as the television crew wrapped up after the day’s shooting. A bank of the bright overhead lights was switched off and one section of the studio went dark.

“Mr. Lewis,” one of the reporters said, “the European critics, especially the French critics, seem to appreciate your work more than the American critics do. Why do you think that is so?”

“Well, it’s not only the critics,” Lewis said. He settled himself into the chair.

“It’s all Europe, they’ve all been very good to me. They’ve acknowledged my work and they look upon it as they look at all cinema. They look a little more carefully than they do in America, that’s all. And I’ve been very fortunate that the European audience has grown for me and gotten larger over time, as the people here have viewed my films and accepted them. The French audience was there first; and now it’s happened in Belgium, in the Netherlands, in Italy, in Spain—Spain has become the biggest club of fanatics that I have, of late. And the last film I made took more money out of Germany than any three films of mine did cumulatively in the past. See, I have to come to Europe when my ego gets way down, after the American critics start to pound me into the cement. Three days in Europe and I feel good again, and then I go home.”

Lewis laughed loudly and the reporters laughed with him.

“The difference is not in the audience,” Lewis said. “I think the American audience is just as good as the European audience. But the critics are something else. I heard that a critic once said the dirtiest words in America are Doris Day, Jerry Lewis and John Wayne. Now, I really don’t know what the hell that means. I guess it’s because I won’t photograph nudity or make dirty films or whatever—I don’t know. But I’m just going to continue to do what I do, without changing my game plan, and I’m not really worried that it doesn’t appeal to some people.”

“What about the American TV audience?” one man said, “You had your own show, but you stopped it.”

“Yeah, No, I didn’t stop it.”

“Really?” the man said. He sounded surprised. “The ratings, you mean?”

“Oh, sure, that’s what stops all television. The ratings. Some of the finest shows that we’ve had on the air went off the air because of the ratings.”

“Because they could no longer get sponsorship?” the man said.

“Well, it’s almost impossible to explain the ratings,” Lewis said. “The ratings go to twelve hundred families, and that’s supposed to represent sixty-four million households.” He made a gesture of disbelief. “Well, I just can’t equate that, you see. I can equate the success of a film by the box office receipts, but television has no box office. And they need some sort of a guide, so they use the ratings as a guide. But it’s a grossly unfair measure to have to work with, and very frustrating for a creative person. So rather than fight that particular system, I just choose to stay away from television.”

“If they would give you the Academy Award, would you accept it?” one young man said with a smile.

“Under a couple—” Lewis looked at the floor and thought a moment. “There would be some conditions.”

Lewis looked at the young man and he stopped smiling. “Like what?” he asked Lewis.

“Like changing the Academy Award structure and making it fair,” Lewis said. “What bothers me is that there’s no category for comedy, nothing that acknowledges my craft or the people who have gone before me, who were the very reason we have a picture industry. At least acknowledge their existence. They got categories in the Academy for the guy who invented a new bulb for the men’s room, but they haven’t got one for comedy.

“Just think that it took them forty some years to honor Chaplin. Now, that angered me; that was wrong. And when I saw Mr. Chaplin walk out on that stage, not even totally aware of what was going on, all I could think of was, ‘Why’d they wait so long?’ ”

Lewis paused for a moment and watched as several men and women wheeled a piece of scenery across the room. “The Academy,” he said finally, “is just very unfair.”

“What about your new film, The Day the Clown Cried? Is there any comic relief in it or is it a straight drama picture?”

“Absolutely straight,” Lewis said.

“Could you give us some details of the story?”

“I could, but I’d prefer not to.”

When will it be released?

“I’m editing it now,” Lewis said. “It’s a little difficult to say when it will be released, because I’m being so cautious about how it’s going to be handled. I don’t want it handled just like the release of another film; it has to be special. And if I can’t get the releasing people who can do what I know is right for the picture, then I’ll have to do it myself. It’s a funny thing about releasing a film. The last picture I made, well—”

Lewis shook his head and laughed.

“Hardly anyone in America saw it,” he said. “My own children didn’t even see it in a theater; I had to run it at home for them. That was because Warner Bros., the company I made the film for, had another film out at the same time, called Woodstock, and they were using all of their energies and resources to push that film. And there was just nothing left over, so my picture died without ever getting a chance. It broke my heart, because I knew I had made a good movie that hardly anybody in my country was ever going to see. Now, that’s the problem of distribution. The fate of your work rests in the hands of some distributor or some studio, and if they have some pornographic film they feel they can make more money with, then you just have to take the consequences. So I’m thinking of doing it myself.”

“In 1960, when you started to direct your own films, did that also mean, at that point, that you were dissatisfied with the directors you worked with or with your work in general?”

“No, I was very satisfied. I worked with some of the finest directors in the medium. I worked with Frank Tashlin and Norman Taurog and George Marshall—I learned from these men, they were my teachers. But I knew I couldn’t always get the director I wanted when I needed him, so I decided that I would have to learn, and do it myself. I certainly wasn’t going to sit still and not make films because I couldn’t get the best. So I decided I was going to be the best. Which I am not, not yet. But I will be.”

Lewis stopped as the reporters all wrote that down.

“Maybe Tuesday,” he added.

The driver took the small red Mercedes through the narrow streets of Cologne at top speed and never turned his head to offer any commentary on the scenery.

The weather was cold and the city looked dark and depressing under the heavy, lead-colored sky as it slid past the windows of the car.

The Mercedes hit a puddle and skidded around a corner in a slight drift, shot up a small cobbled street with heavily barred antique-shop windows on either side, took another corner without braking and roared down a slightly wider boulevard crowded with department-store shoppers bundled against the weather and carrying wrapped parcels.

“Hey, look, I wonder if those are some of the students they told us about,” Harvey said. He pointed out the window toward the sidewalk. Mixed in with the shoppers was a group of young people, walking together in a tight bunch.

“Where are their picket signs?” Harvey said. “Where are their Molotov cocktails?”

The day before, Lewis had gotten word that his 90-minute one-man concert had been canceled because the city of Cologne had experienced a week of student protests and demonstrations. The German people had been vague as to the exact nature of the student unrest, but it was being described along the same lines as the riots that had occurred in Paris in the late Sixties, and there had apparently been several incidents that had approached that state of intensity and violence.

“Did they think these kids were going to toss a bomb onstage while you were singing Rock-a-Bye Your Baby, or what?” Harvey said.

They didn’t know what was going to happen,” Lewis said, looking out at the sidewalk. “But there were so many dignitaries and political big shots coming to the show that they just didn’t feel they could provide adequate security. And you can believe they were plenty worried to kiss away all that money.”

“You still getting paid?”

“Oh, sure,” Lewis said. “For doing nothing.”

“Come sight-seeing in Cologne, folks!” Harvey said. “And now, ladies and gentlemen, if you look to the left of the bus, you will see Cologne’s famous student rioters, coming after your ass! Just wait till they put on their brown shirts, then we’ll really see some action.”

The blond-haired driver raised his eyes to the rearview mirror for an instant, then looked quickly ahead.

The Mercedes looped around a modern-looking skyscraper, a straight shaft of concrete and dark glass, and burst upon Cologne’s famous cathedral.

The cathedral was covered with scaffolding for repairs and it resembled the illustrations from Gulliver’s Travels showing a giant from another world bound with ropes and cables and covered with ladders on which tiny figures scampered about.

The car turned onto a small side street and came to a jolting stop as a large truck backed out of a warehouse into the middle of the road. The driver blew his horn in annoyance, but the truck just sat blocking the way.

By the side of the road, there was another group of young people, larger than the one in the shopping district. They were standing in front of a high brick wall on which several words in German had been written in giant letters with a can of black spray paint. One of the words, not in German, was NIXON.

“What does that say?” Lewis asked the driver. He pointed to the wall.

The driver looked over at the lettering, then back at the truck that was still in the middle of the street. He seemed both embarrassed and annoyed.

“It is nothing,” he said, half turning in his seat. “A slogan of some kind.”

“Yeah, but what does it say?” Lewis said.

The driver turned his head away and honked his horn again, angrily. He answered without turning back.

“It is a slogan for the students,” the driver said. “They are against the Americans and their war. The words say they are murderers.”

The young people stood by the wall, staring out silently at the street. They huddled in front of the thick black letters protectively, as if they were guarding them from theft. They didn’t say anything to anybody. They didn’t talk or laugh among themselves and they didn’t call out to people passing by. They just stood and looked.

The driver gave another impatient blast on his horn, and finally the truck started up again and lumbered out of the way with all the solemnity of a Rose Bowl float. The Mercedes jumped forward with a neck-snapping lurch.

Lewis swiveled in his seat and looked out the back window at the group on the sidewalk. As the Mercedes zoomed down the narrow street, the silent students and their guarded graffito fell back into the gathering dusk.

“There she is,” Lewis said. “There’s the little cunt.”

He braked the Movieola with his hand and made a grease-pencil mark on the film. It cut across the face of a beautiful blonde teenage girl.

“Same little cunt who tried to rape us before,” Lewis said. “Watch her eyes.”

The machine in the Los Angeles studio made a ratchety sound as Lewis backed up the film. He stopped it, started it forward again and cupped his hand against the rim of the small screen to block out the glare from the overhead light.

The screen showed a tracking shot down the length of a barbed-wire fence. Crowded behind the fence was a line of children dressed in ragged clothing, staring straight ahead with vacant eyes, standing completely still. The children’s faces were all European-looking and they had the same pathetic expressions as the faces found on CARE posters.

The blonde girl stood toward the end of the line. As the camera passed in front of her, an almost imperceptible smile showed up at the corners of her mouth and her eyes drifted over to the side, following the lens of the camera as it moved along. As soon as her eyes shifted toward the right-hand side of the screen, the grease mark cut her face in two and Lewis braked the machine.

“There,” he said. “See it? Following the fucking camera.”

Lewis turned and looked at Rusty Wiles, his cutter, who sat on a stool with his arms folded, looking at the screen over Lewis’ shoulder.

“Bet you didn’t see that before,” Lewis said.

“Oh, I saw it,” the cutter said, nodding. “But that kid right before her had such a good look on his face and he’d have to go, too, if we cut. It’s so close.”

Lewis backed the film up and looked at it again.

“The sneaky little bitch,” Lewis said, shaking his head. “Vamping for the camera. She pulled that same thing in another sequence, remember?”

The cutter nodded. Lewis looked at the girl on the screen for a moment.

“I told her to keep her fucking eyes to the front,” Lewis said. “That it wasn’t a beauty pageant. On the big screen, those eyes are going to pop right over as big as life.”

“Pretty face, though,” the cutter said.

“Yeah,” Lewis said. “Everybody wants to be a star. Cut her out.”

Lewis stepped away from the Movieola and the cutter wheeled himself over on his stool, removed the film from the machine and took it over to a bench to recut the scene.

Lewis went to a small refrigerator in one corner of the room and took out a can of beer. He turned on a portable color-television set and sat down in front of it with the beer to wait for the cutter to finish.

“Hey, look, Rusty!” Lewis called out, pointing to the set. “Sherlock Holmes is on the tube.”

The cutter looked over his shoulder. He nodded and turned back to the bench.

On the screen, Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce stood above the body of an elderly man lying in a pool of blood in a handsomely appointed English drawing room. Rathbone looked thoughtfully at the body and said that it appeared as if Sir George had held something in his hand at the time that he was murdered.

“A matchbook, I should think, by the look of it,” Rathbone said, puffing on his pipe.

“Jesus,” Lewis said, drinking from the can. “He knows everything, this fucking Basil Rathbone. He’ll get the guy by the next reel.”

The cutter said that he had fixed the scene and threaded it into the Movieola. Lewis went over and stood next to him and they watched the film.

“Much better,” Lewis said when it was over. “Hundred percent better. There’s no room for Shirley Temple in a concentration camp. What else have you got for me?” He drained the can of beer and tossed it into a metal wastebasket.

“I’ve got this sequence with the guard that I shortened a little. It’ll take a few minutes to put together.” He wheeled himself back to his bench. Lewis sat down in front of the television.

“You know the scene where the guy gets shot?” the cutter said as he worked.

“Yeah,” Lewis said. “What about it?”

“Well, when you showed the film last week, a couple of people asked me if I didn’t think that ran a little long.”

“They didn’t say anything to me,” Lewis said, getting up from his chair. “What do you mean, ‘long’?”

The cutter shrugged. “Just long, I guess. The guy is on the screen a long time. He takes a long time to die.”

“Well, Jesus Christ, Rusty,” Lewis said, “that scene’s going to be an optical. I got faces of kids playing over that scene that I have to put in. It’s not even finished yet.”

“I know,” the cutter said. “I told them you had something planned there.”

“People don’t even know how to look at a rough cut of a fucking film,” Lewis said, his voice getting louder. “It’s still being worked on. I still have things to do with it.”

“Well,” the cutter said, “I told—”

“What if I came up to a guy who was building a house, and he just had the frame up, and I stand there asking him why there aren’t any windows in it yet. How fucking stupid can you get?”

Lewis began to pace angrily about the room.

“Everybody’s an expert, he said. “There’s a fucking genius at every screening. Where were they when the empty pages were in the typewriter? Where were they when we were freezing in fucking Sweden, shooting the film? Too long? Jesus Christ!”

“I just mentioned it,” the cutter said.

“It has to be long for all the dissolves of the faces,” Lewis said. “Besides, it emphasizes the importance of his death. That’s a crucial dramatic point, you know that.”

The cutter nodded and again began to work on the film in front of him.

“It was the same thing with the dance sequence in The Patsy,” Lewis said. “And I told them then that they should just wait till it was fucking finished before they go telling me what’s wrong with it. Just wait till I’m ready.”

Lewis went back and sat down in front of the television. “I don’t know who the fuck asked for their opinion, anyway,” he said over his shoulder.

The Sherlock Holmes movie went off and a car salesman came onto the screen, standing in front of a tired-looking convertible. Lewis flipped the dial and stopped at Jack Paar’s program.

Paar was explaining that he was going to show an exclusive film of the gymnastic team from the People’s Republic of China. “It is quite honestly one of the most remarkable exhibitions I think that I have ever witnessed,” Paar said.

“Oh, shut up and put on the Chinamen,” Lewis said. He got up and went to the refrigerator for another can of beer.

The Chinese gymnasts began leaping through some metal rings, which were so delicately arranged that any body contact at all would knock them over. The men passed through them with effortless grace.

“Big fucking deal,” Lewis said. “In and out of the rings. If they could just work on getting the shirts done right, that would be enough.”

Wiles turned around to look at the set. “I don’t know,” he said. “That looks sort of difficult to me.”

“Oh, yeah?” Lewis said, opening the beer can. “Let me tell you something. If the rings don’t show up, they got no act.”

Joseph Lewis, aged nine, stood motionless in deep left field, wearing an enormous glove on his hand and a green-and-white uniform.

“It’s a shame he doesn’t have more to do,” Mrs. Lewis said. “But at least he’s playing.”

“There’s not much going on in the outfield in this league,” Lewis said. “But you live to play out the season.”

“He looks so small out there,” Mrs. Lewis said. “And in that uniform.”

Lewis knelt on one of the bleacher seats and squinted through a 16mm camera he had set up on an aluminum tripod in front of him. He panned the camera toward left field.

“I don’t know why you brought such a big camera,” Mrs. Lewis said.

“I told you I was going to take some pictures of the baseball player,” Lewis said, framing Joseph in the viewer.

“I thought you just meant regular pictures,” Mrs. Lewis said. “With a hand camera.”

“You can carry this camera in your hand,” Lewis said, still looking through the lens. “Come on, Joby, do something out there.”

Several of the parents sitting nearby stared at Lewis and his movie camera with fascination.

“Momma!” Lewis said suddenly. “He moved! Your kid moved!”

“What did he do?” Mrs. Lewis said, looking out at her son.

“Something with his arm,” Lewis said, working the zoom lens. “I got it on film.”

After three batters had come and gone, the side was retired. Lewis took movies of his son walking in from left field.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do when he gets up to bat,” Lewis said. “I don’t think I’ll be able to watch.”

Joseph came to bat with two outs and a runner on first. He stood at the plate as erect and motionless as he had been in the field, and he held the bat directly in front of him, perpendicular to the ground, like a pole vaulter during the singing of the national anthem.

The first pitch went well over his head and Joseph did not move a muscle.

“Good eye, Joseph!” the coach yelled from the side line.

“Good eye?” Lewis said from behind the camera. “He’s scared stiff. He doesn’t know what the hell he’s doing. I can’t keep looking, Momma.”

Joseph took two more high pitches without ever moving out of position.

“One more,” Lewis said. “Come on, you little bastard, throw one more lousy pitch.”

But before the pitcher could go into his windup, the runner on first broke away for second base. The umpire immediately called him out, on the grounds that, in little league, it is illegal to steal a base before a pitch is thrown.

Suddenly, the field was filled with people. The other team, whooping loudly, began to run in for its turn at bat. Joseph’s team was on its feet and circling the umpire, protesting the call. The coach argued vehemently that, according to the rules, the runner had only to return to first and was not out. The other coach rushed over, shaking his head.

Throughout all the commotion, Joseph stood exactly as he had before, completely still, with the bat pointing straight up in the air.

“You tell him, coach!” Mrs. Lewis shouted in encouragement. “That umpire doesn’t know the rules!”

“Jesus Christ!” Lewis said, following the action with the camera. “My kid’s in the middle of a riot. And he still isn’t doing anything.”

Finally, it was decided that the runner was not out. The opposing team would return to the field and the runner would return to first base. Joseph was still at bat and he watched without blinking as he was thrown a fourth high pitch.

Joseph set the bat down neatly and walked to first base.

“Thank God,” Lewis said, panning with him as he took the base. “He got on.”

Lewis shut off the camera and sat down with a loud sigh. Mrs. Lewis applauded and waved across the field at her son.

“You did good today, Joby,” Lewis said as they went into the house. “You got on base and you didn’t get out.”

“What’s so good about walking?” Joseph asked. He set his glove and cap down on the hall table. “I didn’t get a hit.”

“Well, that was the fault of the pitcher,” Mrs. Lewis said. “He didn’t throw you anything that you could hit. Besides, it doesn’t matter how you get on base, it’s getting there that counts. Right, Daddy?”

“Right,” Lewis said. “And tomorrow you and I will go out and practice standing with the bat. A little practice with your old man and you’ll be ready for the majors.”

“In a year or two,” Mrs. Lewis said with a smile.

Lewis told Joseph that he had a present for him and went upstairs. He came back down with a giant assortment of crayons in a flat metal box covered with cellophane.

“I went to the stationery store to get some pens,” Lewis said, “and I saw this. I thought you might like it.”

Joseph thanked his father for the gift and sat down to open it. The box had a decorated lid that had been removed from its hinge and wrapped against the bottom of the tray, so that the crayons could be displayed through the cellophane. Joseph took both halves of the box and began to put them together.

“Here, let me help you with that,” Lewis said, taking the box in his hands. “These are tricky sometimes.”

Lewis sat down next to his son and tried to fit the lid onto the hinge. He worked with it for a few minutes, but the lid kept popping loose.

“Just one minute more,” Lewis said slowly, concentrating. “This little wire has to slide in there, Joby, see? See the little space? But it keeps coming out.”

The telephone rang and Mrs. Lewis came into the room to tell her husband that there was a long-distance phone call for him from Germany.

“OK,” Lewis said without looking up from the box. “I’ll be there in a second. Just as soon as I get this put together.”

Mrs. Lewis watched him struggle unsuccessfully for almost a minute, and then she said, “Daddy, you better take this call. They might be calling direct.”

Lewis nodded and kept working. Mrs. Lewis left the room and came rushing back a few seconds later.

“Daddy!” she said. “They’re calling direct! Please come to the phone!”

“My son is waiting for me,” Lewis said, as the lid went popping into his lap again. “I have to finish this.”

“You can do that later,” Mrs. Lewis said.

Lewis did not answer, just kept working with the hinge.

“Lewis!” Mrs. Lewis said finally. “Take the call! Do that later.”

“Can you wait a few minutes while Daddy takes this call?” Lewis said to his son. “Then I’ll fix this for you, OK?”

“I’ll try,” Joseph said.

“You’ll try and wait?” Lewis said, getting up.

“I’ll try to fix it,” Joseph said.

Lewis set the box down and went into the next room.

Joseph took the box and put it on his lap. He looked at it for a while, then took the crayons out of it and turned it over and looked at it some more. Finally, he picked up the lid and began to work it onto the hinge. After a few minutes, the lid clicked and fell into place. Joseph raised and lowered it experimentally a couple of times and it moved on the hinge smoothly. He was putting the crayons back in as Lewis returned.

Joseph smiled at his father and worked the lid for him.

“Oh,” Lewis said. “Did you get it put together, Joby?”

“I put the wire through that bump,” Joseph said. “Right there.” He held the box out and indicated the spot.

“That’s very good, sweetheart,” Lewis said. He picked up the crayon box and studied the hinge. “I guess Daddy must have been doing it wrong.”

[Featured Image and picture of Milton Berle via Wiki Media Commons; “Hotel Lobby, Miami Beach” by Robert Frank (1955), via The Art Institute of Chicago; “Woman on the Street with Her Eyes Closed” by Diane Arbus (1956), via The Art Institute of Chicago; “Sisters, Miami Beach” by Jonas Dovydenas (1972), via The Art Institute of Chicago; Little League, via Wiki Media Commons]