The Heart of the Matter

The presence of the Philby papers in London was still a closely guarded secret when I stumbled on them through an inadvertent slip by Graham Greene’s nephew. I’d found him, the nephew, in the cluttered basement of his Gloucester Road Bookshop, where he’d been preparing for the imminent sale of the late novelist’s personal library.

I’d come to see him about one volume from that library in particular, Greene’s copy of My Silent War, the memoirs of Kim Philby, the spy of the century. It had been reported that Greene had made some cryptic annotations in the margins of the Philby book, and I hoped they might provide a clue to the strange story I was pursuing. A story about a possible deathbed revelation Graham Greene had had about Philby. A story that epitomized the maddening, elusiveness of the man: the way those who felt they knew Philby, who thought they’d finally penetrated to the truth beneath the masks, may never really have known him at all.

Greene had first come to know Philby when the two were working for the British Secret Intelligence Service during World War II and Philby was the brilliant, charming counterintelligence specialist who disguised his intellectual arrogance with a disarming stammer.

Later, Greene would learn that Philby was disguising a lot more than that: that he’d been Stalin’s secret agent, burrowing his way into the upper reaches of the British establishment since the 1930’s. And still later—after Philby had been exposed as a long-term Soviet mole, indeed the ur-mole, the legendary Third Man, the most devastatingly effective known double agent in history, after Philby had surfaced in Moscow in 1963, a hero of the K.G.B.—Greene and Philby had struck up a peculiar and controversial friendship.

They’d become correspondents, confidants and—after perestroika had permitted them face-to-face reunions in Russia—something like soul mates. Greene seemed to pride himself on being the one Westerner who truly understood the endlessly enigmatic Philby; knew him with all the masks off.

But then, in 1991, as Greene lay dying of a blood disease in a Swiss hospital, a letter reached him throwing all that into question. It suggested Philby had a wild card up his sleeve he’d never disclosed.

The provocative new take on the ambiguity-riddled Philby question came in the form of a letter from Greene’s biographer Norman Sherry, who’d been researching Greene’s Secret Service connections. Pursuant to that, Sherry had been conferring in Washington with Anthony Cave Brown, the espionage historian then researching a forthcoming Kim Philby biography. Cave Brown was the intrepid spy sleuth who’d first revealed (in Bodyguard of Lies) the details of the elaborate D-Day deception strategy—the way the Allies used the “double cross system” to blind Hitler to the truth about the Normandy landing.

Cave Brown had put forth a startling proposition to Greene’s biographer: that Kim Philby might have been part of an even more complex deception operation than anyone had imagined—a double double-cross.

It had been whispered about before in the West; it had been debated (we now know) in the inner sanctums of the K.G.B. itself. But the theory the two biographers were weighing was deeply shocking: Kim Philby, famous for deceiving the British by posing as a loyal agent of the Crown while really working for the K.G.B., might actually have been deceiving the Soviets by posing as their agent on behalf of the Brits. Could it be, Sherry wrote Greene, that Philby, regarded as the most destructive and demoralizing Soviet penetration of the West, was actually a Western agent penetrating the K.G.B.’s Moscow Center?

It’s a notion that I suspect might have been extremely galling to Greene. After all, he had risked his reputation as a judge of human character (a matter of pride to most novelists), as a man able to see into “the heart of the matter,” by writing an extraordinarily sympathetic introduction to Philby’s 1968 K.G.B.-blessed memoir, My Silent War, an introduction that touched off a bitter row in Britain about the meaning of loyalty and treason.

Greene’s introduction portrayed Philby not as a cold and ruthless traitor with the blood of betrayed colleagues on his hands (as most in Britain saw him) but as an idealist who sacrificed his friendships to a higher loyalty. A man whose belief in Communism Greene memorably—and maddeningly to many—compared to the faith of persecuted Catholics in Elizabethan England, who clandestinely worked for the victory of Catholic Spain. Greene portrayed Philby as someone who served the Stalin regime the way “many a kindly Catholic must have endured the long bad days of the Inquisition with this hope … that one day there would be a John XXIII.”

Graham Greene would turn out to be Kim Philby’s final fool.

Many in Britain have never forgiven Greene his defense of Philby, still an unhealed wound in England. Some speculate his pro-Philby stand cost Greene a knighthood, and a Nobel Prize.

Imagine Greene’s distress, then, at the possibility that Philby had been not a Soviet double agent but a British triple agent. Greene had gone out on a limb to portray Philby as a passionate pilgrim, a sincere devotee of the Marxist faith—radically innocent rather than radically evil. But if, in fact, his friend had all along been an agent of the Empire, a hireling of Colonel Blimp, it would mean that Philby had been laughing at Greene. Not merely laughing at him, but using him, using him as cover. Graham Greene would turn out to be Kim Philby’s final fool.

“As a matter of urgency,” Cave Brown told me, “Greene summoned up enough energy to send for his papers, for all his literature relating to Kim and certain letters from him.”

Cave Brown believes that Greene spent those last hours playing detective, sifting the literature and his memories of Philby for clues to the hidden truth about the role the ultimate secret agent played in the secret history of our century. And that Greene was preparing to respond to Sherry’s query with his last word on the Philby case. It would have been Greene’s summa, his ultimate espionage thriller. With little time left to live, Graham Greene was in a race against the clock.

The Original Disinformation Virus

Why does Kim Philby continue to cast such a dark spell over the imagination? Why is Philby such a magnetic specter to novelists like Greene and John le Carré (whose Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy enshrined the Philbian mole Bill Haydon at the dark heart of cold war literature), to playwrights like Alan Bennett and poets like Joseph Brodsky (the Russian exile laureate, whose rage at the sight of Philby’s face on a Soviet postage stamp inspired a magnificently vicious 10,000-word tirade in The New Republic)? In part, it’s the same sort of horrified fascination that fueled the sensation over Philby’s mercenary successor mole, Aldrich Ames of the C.I.A.: a fascination with the primal act of betrayal itself. Dante reserved the Ninth Circle of Hell for the Betrayer. Even in an age jaded by serial killers, the crime of treason still has a primitive power to shock, treachery a still-compelling ability to mesmerize.

The mole, the penetration agent in particular, does not merely betray; he stays. He doesn’t just commit a single treacherous act and run; his entire being, every smile, every word he exchanges, is an intimate violation (an almost sexual penetration) of all those around him. All his friendships, his relationships, his marriages become elaborate lies requiring unceasing vigilance to maintain, lies in a play-within-a-play only he can follow. He is not merely the supreme spy; he is above all the supreme actor. If, as le Carré once wrote, “Espionage is the secret theater of our society,” Kim Philby is its Olivier.

And, like only the very best actors, Philby didn’t merely hold up a mirror to human nature. He revealed dark shapes beneath the surface only dimly glimpsed before, if at all—depths of duplicity, subzero degrees of cold-bloodedness that may not even have been there until Philby plumbed them. Once in an interview on another subject, the essayist George Steiner made the provocative suggestion to me that the nightmare world of the death camps might not have been realizable had not Kafka’s imagination first embodied their possibility in his fiction. I have a similar feeling that the Age of Paranoia we’ve lived in for the last half century—the plague of suspicion, distrust, disinformation, conspiracy consciousness that has emanated like gamma radiation from intelligence agencies East and West, the pervasive feeling of unfathomable deceit that has destabilized our confidence in the knowability of history—is the true legacy of Kim Philby.

Philby pushed the permutations of doubleness—double identities, double meanings and double crosses—into triply complex territory, into the bewilderment of mirrors we’re still lost within. He’s the high priest of the Age of Paranoia, the original disinformation virus, and we’re still only beginning to learn how much of the secret history of the century bears Philbian fingerprints.

Unlike the spy scandals of the ’40’s and ’50’s, the Philby case has been a slow-motion series of revelatory detonations stretched out over decades. One reason the truth has been so slow in emerging is that it’s just so embarrassing. Even before James Bond, the spymasters of the British Secret Service enjoyed a worldwide reputation for infinite subtlety, invincibility and aristocratic élan. Philby made them seem like bumbling fools who were so blinded by class prejudice they couldn’t imagine that a man from all the right schools and all the right clubs could betray his blue-blood legacy.

Indeed, the deeply chagrined British Government clamped such a tight lid on the Philby case that it took nearly five years after he defected to Moscow in 1963 for the most embarrassing truth to come out (in a ground-breaking Sunday Times of London investigative series): that Philby was no ordinary midlevel spy; that, in fact, he’d been one small step away from being named to one of the most powerful posts in the Western world at the height of the cold war—Chief of the British Secret Service. (Although British officialdom pooh-poohed this assertion at the time, it was confirmed to me in London this spring by Sir Patrick Reilly, the former head of the Joint Intelligence Committee, the board of spy mandarins that oversees the selection of “C,” the chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service.)

Philby was no less a nemesis of the American spy establishment. In the final act of his active duty career in the West, before the spotlight of suspicion fell on him in 1951, Philby was stationed in Washington, where, as chief British liaison with American intelligence agencies, he charmed the C.I.A.’s deepest secrets out of his principal contact, James Jesus Angleton, the man who would go on to become legendary as the C.I.A.’s chief mole hunter. This shattering betrayal left behind a destructive legacy of distrust and paranoia in Washington—principally in Angleton’s mind—reverberations of which would come to plunge the C.I.A. into civil war for decades afterward. And in an incredible final act that closed the circle of deceit, in what may have been his last operational mission, Philby indirectly collaborated with Aldrich Ames in solving a high-level mole case for the K.G.B.

But these spy dramas only begin to capture the extent of Philby’s role in the secret history of our century, the extent to which he was far more than a cold war spy—he was a secret shaper of the very landscape of the cold war.

We know, for instance, that Philby was, in effect, talking to Stalin throughout World War II. Stalin considered reports from Philby “particularly reliable,” writes the intelligence historian John Costello, the first Westerner to get access to Philby’s operational files.

What is less well known is that Philby was, in effect, talking to Hitler, too. Cave Brown recalls a memorable conversation he had with Sir Ronald Wingate, a key member of the secret Churchill Cabinet department that formulated elaborate strategic deceptions like the one that kept Hitler guessing wrong about the D-Day landing.

“You were talking directly to the Devil himself weren’t you?” Cave Brown asked Sir Ronald while they were out on a pheasant shoot.

“We could have a message on Hitler’s desk within a half hour,” Wingate replied. “Sometimes 15 minutes at the right time of day.”

Then Cave Brown learned the name of the man who was one of the chief conduits in these conversations with the Devil: Kim Philby.

As head of the Iberian section of M.I.6 counterintelligence, Philby was running agents in Madrid and Lisbon who were so highly trusted by the Nazis that the words he fed to them for transmission to the Abwehr would be whispered to Hitler almost at once.

In Catch-22, Joseph Heller memorably envisioned all the mighty forces of World War II, Allied and Axis, manipulated by a single low-level communications specialist, ex-Pfc. Wintergreen, an all-knowing, wise-guy proto-hacker of the war’s information flow. In fact, Kim Philby was the real ex-Pfc. Wintergreen—talking to Stalin, talking to Hitler, listening to Hitler through his command of the Ultra Secret, the code-breaking material produced by the famous “enigma machine” that read the ciphers of German military intelligence. And just to complete the circle, Philby was also influencing Churchill. Every day the Prime Minister would eagerly await his briefings by Philby’s M.I.6 boss, Stewart Menzies, who would bring Churchill a digest of Hitler’s secrets, some of the choicest bits prepared by Kim Philby. Similarly, Philby could manipulate F.D.R., as well, through whatever he chose to pass on to his junior partners in United States intelligence.

Without a doubt, the mind of Philby was a key junction box, a node, a filter through which some of the most secret messages of the war were routed. But the question remains: Was Philby merely a courier or was he a creator?

That question, I believe, is at the heart of the continuing fascination with Philby: we’re still not sure whose game he was playing, or what his own game really was. He remains a one-man enigma machine whose true aims and motivations have yet to be fully decrypted.

The Notional Philby

I’d first written about Philby some 10 years ago in the context of his complex duel with C.I.A. mole-hunter Angleton and the espionage equivalent of three-dimensional chess that the two men seemed to be playing with phantom moles, false defectors and putative penetrations. I’d advanced a kind of Philbian solution to the still-unresolved mole hunt controversy—the “notional mole” gambit. Angleton had turned the C.I.A. inside out looking for the American Philby. I suggested the possibility that there never was a real mole, not of the stature of Philby, not while Angleton was there anyway. But that Philby had deliberately planted the false suspicion in Angleton’s mind that the K.G.B. had a mole within the C.I.A. (thus the phrase “notional mole” coined by Philby’s Double Cross colleagues of World War II) in order to provoke the disruptive and destructive mole hunt that followed—one that paralyzed the agency with paranoia and ultimately claimed Angleton himself as a suspect and victim.

What struck me in looking back on it, in reviewing the vast Philbian literature and mole war chronicles, was that, like many writers on the subject, like James Angleton himself, I had been seduced on the basis of fragmentary evidence by the image of a Notional Philby: an image of Philby in his post-1963 Moscow period that Philby himself had assiduously cultivated in his memoirs and correspondence with Westerners. An image of Philby as the peerless mastermind, the Ultimate Player in the East-West intelligence game, always operating one level deeper than anyone else. It was a romanticized, almost cinematic image: Philby still the unflappable Brit aristo waiting for the cricket scores to arrive at the Moscow post office, then returning to the K.G.B.’s Moscow Center to run a few more rings around the best intelligence minds of the West.

How much truth was there in it? In the aftermath of the collapse of the system he sold his soul for, with the opening of the K.G.B. archives and the loosening of the tongues of the former K.G.B. men who were his colleagues, we suddenly have a wealth of new information about Philby’s career since 1963, when he first reached Moscow. We have more information, but do we have more answers? In the hopes of sorting out the new clues to the mind of Kim Philby, I undertook an odyssey into the infamous “wilderness of mirrors” he’d bequeathed us, talking with spooks and spymasters in Washington, London and Moscow, with some of Philby’s victims and bewildered successors; trading theories with mole war chroniclers like Cave Brown, Nigel West of Britain and Cleveland Cram of the C.I.A. It was an odyssey that led me eventually to the bookshop basement in South Kensington and the tip-off about the hush-hush cache of Philby papers in London.

I’d asked Greene’s nephew about the cryptic marginal annotations in Greene’s copy of Philby’s memoirs, thinking they might contain a clue to Greene’s deathbed detective work. The nephew, a friendly, intelligent fellow named Nicholas Dennys, confirmed that the annotations consisted of passages that had been suppressed in the British edition of the book by the British Official Secrets bureaucracy but had survived in the American edition. And that they’d most likely been made long before Greene’s final days.

A false trail perhaps, but then Dennys let slip a clue to a real one.

Why, he asked, had I chosen this time to come to London to pursue a Philby story. Was it because of the papers?

What papers? I’d asked him.

The Sotheby’s consignment, he replied offhandedly. It seemed that Philby’s Russian widow, Rufina (his fourth wife), had gathered up all the manuscripts, books and memorabilia he had left behind in his Moscow apartment after his death and had engaged Sotheby’s to put them all on the block.

But when I called Sotheby’s to inquire about the Philby papers, there was nothing offhanded about their reaction. How did I find out? Who had I talked to?

It seems that they’d promised a world exclusive to a British journalist whose wrath they feared. In addition, they were nervous about reception of the news of the Philby sale—scheduled in London for July 19—about charges of profiting from the fruits of treachery. (And, in fact, when word of the sale did become public, the heat from the Tory press was so great the auction house decided to withdraw some of the more frivolous Philby items, among them his pipes, Homburg and martini shaker.) But confronted with a fait accompli, the Sotheby’s people agreed to let me study the Philby documents, provided I didn’t break the embargo.

What I found, when I got to see the consignment from Moscow, was a strange mixture. There were letters, diaries, memoranda, a secret speech to K.G.B. spy luminaries. There were tributes and tacky trophies from K.G.B. and Eastern European spy fraternities; posthumous tributes to Philby’s father, the famed Arabian explorer St. John Philby. There were photographs of Philby on safaris to Siberia and Cuba; Philby with the East German spymaster Markus Wolf, the crafty intriguer often identified as the model for George Smiley’s arch-nemisis Karla in the le Carré novels. There was correspondence between Philby and Graham Greene, filled with catty comments about Brit Lit contemporaries like Malcolm Muggeridge and grandiose geopolitical pipe dreams the two old spies cooked up, most notably a Greene scheme for a joint U.S.-U.S.S.R. commando raid to free the Ayatollah’s hostages in Iran. And a detailed request to a K.G.B. protégé in London for special English brands of coarse-cut orange marmalade and lime pickle.

And then there was the unfinished autobiography. Five chapters in manuscript pages whose publication the K.G.B. had apparently prohibited.

A fairly safe general rule when reading Philby’s prose is to assume he’s lying or distorting—and then try to divine the truth the lies are attempting to conceal.

It’s a tricky game, but there were some moments, particularly in the childhood memories he recounted in this autobiographical fragment, when I felt the real Philby, or perhaps more accurately, the original Philby, seemed closer to the surface.

One moment, one childhood memory in particular, stood out from the rest. A moment I came to think of as a kind of metaphysical Rosebud of the Philby psyche. A moment of communion between Philby and his colorful, eccentric explorer father. One that probably leapt out at me because fresh in my mind was a remarkable vision of Philby and his father in the flesh that had been vouchsafed me shortly before I left for London.

The Two Philbys

Beirut, 1959. Dawn outside the Kit-Kat Klub. Anthony Cave Brown, then a correspondent for The Daily Mail, is gazing out from his hotel balcony.

“I’ll never forget that morning,” Cave Brown told me, “because at that hour of dawn the entire sky was suffused with a dramatic ocher color—threatening, ominous, mystical. It was the shamal, the wind from the Arabian desert.”

Then he heard voices filtering up from the Avenue des Français, home of the Kit-Kat Klub and other seedy belly-dance lairs. And out of the ocher mists of dawn, staggering up the street came the two Philbys, arm in arm, singing an obscene song.

There was Philby the Elder, Harry St. John Bridger Philby, then near 70, “potbellied and satanic looking,” Cave Brown recalls. Soon to die but still a living legend, St. John was one of the great Arabian explorers and intriguers, a rival to Lawrence of Arabia and the first Westerner to have traversed and mapped the vast, forbidding and forbidden Empty Quarter of the Saudi interior. Adventurer, scoundrel, convert to Islam, St. John (pronounced sin-jin) had turned against the Empire during World War I, when the Brits backed the puppets of his rival Lawrence against Philby’s patron Ibn Saud; bitter over this loss, he’d then avenged himself on the Crown by helping to spirit the Saudi oil concession out of its clutches and into the hands of American oil companies. At the time of the Kit-Kat Klub sighting, St. John, known then as Hajj Abdullah, was living in a villa in a mountain village with his Saudi harem-girl, still up to his neck in Mideast intrigue.

As was his son. Nicknamed Kim by his father (after Kipling’s boy-spy who played a part in the Great Game of intrigues between the Brits and Russians in 19th-century Central Asia), Harold Adrian Russell Philby had gone on to play an even greater game of his own. He’d followed in his father’s footsteps onto the imperial playing fields of Westminster public school and Trinity College, Cambridge, and then into the Imperial Secret Service, which he would, like his father, betray.

At that point in Beirut, Kim Philby was living in the strange shadowy limbo he’d been condemned to since 1951, when he’d come under suspicion of being the Third Man in the great Burgess and Maclean spy scandal. (Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, two highly placed British diplomats who were Cambridge classmates of Philby and recruits to his Cambridge “Ring of Five” spies, defected just before Maclean was to be arrested on suspicion of espionage. Part of the subsequent sensation over these “spies who betrayed a generation” was that a mysterious, unidentified Third Man had tipped them off.)

Forced to resign in 1951, he’d been subjected to repeated interrogations without cracking. Publicly cleared in 1955 but still suspected privately by Western security services, Philby had been sent to Beirut by the Brits in 1956 to pose as a journalist—in part to spy for them, in part to see if he’d continue to spy for the Russians. Of course, he did both, playing and being played in a doubly complicated game in which he served as a two-way conduit for disinformation.

It’s hard to imagine a father-son team causing the Crown more trouble. That eerie ocher dawn in Beirut, the two Philbys were walking, staggering arm in arm, but were they working hand in glove?

They were, in any case, harmonizing together that morning on an old R.A.F. dirty ditty, one that lamented the passing of a lady of the night named Lulu. “What shall we do,” the song asks, for—well—carnal delight, “when Lulu’s dead and gone?”

I suspect it was an emblematic moment for Cave Brown, this vision of the two Philbys. He calls his forthcoming Philby biography Treason in the Blood, and what distinguishes it from previous works on Kim Philby is the extent to which it’s a father-son story. Cave Brown sees a factual, even genetic link in their taste for treachery. Reading Cave Brown’s manuscript, one comes away with an impression of the two of them as a kind of family firm of global troublemakers whose self-aggrandizing game playing transcends any loyalties they might have had to lesser entities East or West. But there’s something primal, indelible about that image of father and son in the Levantine dawn. The empire, like Lulu, might be dead and gone, but the two Philbys survive, two successful predators sending out an obscene howl of triumph and defiance before setting off in search of fresh treacherous pleasures.

Spy Glass Hill

Where does the Philby story really begin? Previous Philby literature has focused almost microscopically on the cloistered quadrangles of Cambridge in the 1930’s, on the hothouse Marxist cells that flourished amidst the sherry parties and secret societies, on the overlapping erotic and political relationships amongst the privileged upper-class youth who were seduced by each other and by canny Russian case officers into what became known as “The Ring of Five,” the single most deadly spy ring in history.

Cave Brown’s biography differs from Cambridge-centered Philby studies in that he finds the true locus of origin of the Philby mystery in the Middle East, in the father’s formative ventures into espionage, which, he says, set the pattern for the son. Indeed, he goes further, asserting in his book (due out from Houghton Mifflin this fall) that Philby the Elder, regarded by most until now as far right politically, may have been recruited by Soviet intelligence in the Red Sea port of Jidda shortly before his son was approached in England. Cave Brown says he was told by a former K.G.B. official, Oleg Tsarev, that St. John Philby was a “Soviet asset.” Cave Brown also raised the possibility with me that the father’s contacts with the K.G.B. in the Mideast may have led to the son’s being targeted for recruitment. He almost goes so far as to suggest the father was running the son, that Kim was his agent.

I’ve come to believe that, in a sense, St. John Philby did recruit his son into the Great Game. But it was more a metaphysical than literal recruitment, and I’d put it much farther back in time and place, not in the Middle East itself but in a map of the Middle East.

In the opening pages of his unpublished memoir, Philby depicts himself as a wistful loner of a child—collecting butterflies, spending long hours drawing imaginary maps. Map making was his only real passion. Not ordinary Atlas-type maps, but “maps that could be invented,” Philby writes. “This discovery resulted in [my drawing] a long series of imaginary countries with complicated promontories and inlets and improbably situated hills. My grandmother criticized me for calling all of them Spy Glass Hill.”

Philby was not an anti-imperialist, but a personal imperialist, an imperialist of the self, who used his power to impose his own vision on the globe.

Perhaps, in some sense, the young Kim Philby was drawing maps of his own lonely island psyche. But the true apotheosis of his map-making obsession, the moment that blissfully, sublimely united him with his long absent father, came on the occasion of St. John’s return from one of his fabulous Arabian expeditions. This, Kim says, was his first conscious memory of his father: “I remember he took me through Kensington Gardens to the Royal Geographical Society. There, in an upper room he sat me on a stool beside a huge table covered with large sheets of blank paper, ink bottles, pens and a lot of pencils sharpened to the finest point imaginable. My father was drawing a map, and, as far as I could see, an imaginary map at that because he had no Atlas to copy from.”

He was, most probably, filling in the blank spaces in the notorious Empty Quarter, giving reality to what was until then a largely imaginary landscape. Kim admits to two feelings about this spectacle: first “admiration” and then “wonder” that this was his father’s work. To Kim, it was the supreme form of play.

A fierce debate has long raged in Philby literature over the question of his true motivation: Was he driven solely by sincere dedication to the cause of the oppressed proletariat, as he claimed to be? Later on in the autobiographical manuscript, Philby gives us this pious version, perhaps designed for the eyes of his ultimate editors, the K.G.B.

From the earliest age, he says, he felt “a sympathy for the weak” and the underdog. The plight of the poor lepers. “Why,” he says he wondered at an early age, “did Jesus cure only one leper when he could have cured them all?” Skepticism of this sort led him to question other established notions—of nationhood and empire—and, he declares, he “became a godless little anti-imperialist by the age of 8.”

Perhaps this is true. But reading the yellowing typescript of the unpublished autobiography in Sotheby’s London offices, I became convinced that the map-making imperative is the telltale heart of the matter. That, for Kim Philby, espionage, on the grand geopolitical scale he came to practice it, was a kind of map making, or map remaking, a way of creating the conceptual landscape of the world, the contour lines of desire and hostility, trust and distrust, power and weakness.

In a sense, then, Philby was not an anti-imperialist, but a personal imperialist, an imperialist of the self, who used his power to impose his own vision on the globe, to make the Great Powers navigate by his charts. To make his own mischief on a grand scale. To make his own map.

The Black Bertha File

Consider, for instance, the new information about Philby’s role in the Hess case. It’s hard for those of us born afterward to recapture the kind of worldwide sensation made back in May 1941 by the news that Hitler’s faithful No. 2, Rudolf Hess, had parachuted into the Scottish countryside on some kind of peace mission. Imagine, for comparison, the headlines Dan Quayle might have made if, at the height of the gulf war hostilities, he’d parachuted into Baghdad on a self-proclaimed mission to talk peace with Saddam.

Many questions about the Hess flight have yet to be answered with assurance, because, as espionage historian John Costello puts it, “the British Government seems more determined than ever to keep the final truth of the Hess affair locked in the closet of official secrecy.” Another historian I spoke to claimed that the Royal Family itself (“I suspect it’s the Queen Mum”) had been the real source of objection to releasing what’s left, perhaps because embarrassing evidence of the Windsor family’s sub rosa contacts with the Third Reich over a separate peace might be disclosed.

Whatever the case, the 1941 Hess flight came at a pivotal moment in the war and a pivotal moment in Philby’s career as a spy. Seven years earlier, Philby had left Cambridge to go to Vienna, where, with other Oxbridge leftists like Stephen Spender, he’d participated in the doomed struggle of the Socialist workers against the proto-Fascist Dollfuss regime. It was there in Vienna he first found the heady thrill of being in the white-hot crucible of history in the making, of fighting the advance guard of Hitlerism, if only as a fringe player. He became a courier in a Communist underground network and lost his virginity in the snows of the Vienna woods, to an Austrian Communist Jew whom he then hastily married to help escape the police.

When he arrived back in London, he was ready. A Soviet intelligence officer made an approach on June 1, 1934, in Regent’s Park. His name was Arnold Deutsch and, 50 years later, in his autobiography, Philby seems still under the spell of Deutsch’s magnetism, an almost sexual seductiveness. Not surprising perhaps, because Deutsch was a charismatic former sexologist, originally a follower of Wilhelm Reich, the Freudian Marxist schismatic who made healthy orgasms the key to personal as well as societal revolution. (The lingering influence of this doctrine on Philby may be glimpsed in a not entirely facetious inscription in a book that turned up in the Sotheby’s consignment. The book was a gift to Melinda Maclean, the wife of his fellow spy, Donald; Philby betrayed his own wife to woo her away from his friend. The inscription to Melinda reads: “An orgasm a day keeps the doctor away.”)

Deutsch painted a romantic picture for Philby: the struggle for the future was being waged all over the world. The Soviet Union was alone in resisting Hitler; the British Secret Service was forever scheming to destroy the world’s only Socialist state; the Soviets needed someone sympathetic within the citadel of these incessant schemers. That would be Philby’s long-range penetration mission: do anything he could to get inside the British Secret Service. In fact, he came close to becoming head of it.

But it was slow going at first; Philby publicly ditched his left-wing politics, and soon his left-wing Austrian wife. For several years, he posed as a pro-German sympathizer, then used his right-wing contacts to make his way to Franco headquarters in Spain in the midst of the Civil War. Originally sent there as an advance man for a possible Soviet-sponsored assassination attempt on Franco, he bootstrapped his way into a position as London Times war correspondent, eventually receiving a prestigious decoration, the Red Cross of Military Merit, from the dictator he’d originally been sent to kill.

Finally, in 1940, shortly after the fall of France (which he covered for The Times), he got the invitation he’d been hoping for, an invitation to join the British Secret Service. He’d begun in guerrilla training operations and was just about to transfer to the true brains of the outfit, the foreign counterintelligence department of M.I.6, when Rudolf Hess fell out of the sky.

At that moment, huge forces in the world were on the verge of momentous shifts. Hitler was about to make apparent his fateful choice between an invasion of England in the West and an attack on his then-ally in the East, the Soviet Union. There were factions in both Britain and Germany hoping to arrange a peace between the two “Aryan” powers to free Hitler’s hand for an attack on the Bolsheviks. Stalin suspected a deal was being made behind his back, and Hess’s flight seemed to confirm his suspicion. He lashed his intelligence chiefs into finding out what was really going on, who was betraying whom.

After 50 years, we still don’t really know for sure, but what we do know now is what Philby told Stalin was going on. This came to light three years ago when the successors to the K.G.B. released the contents of its “Black Bertha” file on Hess (“Black Bertha” was reportedly Hess’s nickname in the homosexual underground of Weimar Germany), a file containing the texts of Philby’s reports to Stalin on the Hess Affair.

How reliable were they? On the basis of Philby’s reports, Stalin came to believe the most paranoid interpretation of the Hess flight that (as John Costello describes it) “Hess had been lured by an M.I.6 deception to fly to Scotland. He apparently had not only done so with Hitler’s knowledge but with a genuine offer of a final peace deal before the impending attack on the Soviet Union.”

There are some who believe there really was a plot by M.I.6 to lure Hess to England for one reason or another. Most, however, take the position of the Cambridge historian Christopher Andrew and his co-author, former K.G.B. Col. Oleg Gordievsky: that Philby was innocently in error in his reports to Stalin, “that he jumped to the erroneous conclusion that [Hess’s flight] was evidence of a deep laid plot between appeasers in high places and the Nazi leadership.”

But was it just a mistake? There is another, more sinister interpretation to be made of Philby’s reports to Stalin. An interpretation that suggested itself to me after a conversation with Lord James Douglas-Hamilton, the son of the Scottish peer Hess had come to England to see and the author of a respected book on the case based on his father’s private papers.

Douglas-Hamilton, now an M.P. for Edinburgh, told me that, from his study of the Black Bertha file, he’d concluded that Philby hadn’t made an innocent error but rather “he lied.”

He lied, Douglas-Hamilton says, “by claiming that he was present at a dinner in Berlin when my father supposedly met Hess—which never happened. My father never met Hess.” Douglas-Hamilton believes Philby lied about that detail and others in his report to exaggerate his knowledge of the affair, to bolster the credibility of his conclusion that the Hess flight was part of a plot by the Bolshevik haters in the British Secret Intelligence Service to unleash Hitler on the Soviets.

We know the effect of Philby’s reports: Andrew and Gordievsky conclude that “contributing to Moscow’s distrust of British intentions was to be one of Philby’s main achievements as a wartime Soviet agent.”

Stalin’s paranoia over the Hess case never diminished; he berated Churchill about it as late as 1944. And Philby’s interpretation of the Hess affair planted bitter seeds of suspicion and distrust that would bear fruit in the swift shattering of the wartime alliance after 1945 and in the Iron Curtain landscape of postwar Europe.

Of course, there were real enough reasons for distrust between Moscow and London, but what Philby did was not report but deliberately distort.

To what end? Later, in his Moscow years, Philby liked to portray himself as a faithful servant of the Soviet people and the cause of proletarian internationalism. But, in fact, here in the Hess case at least, he was using the immense leverage of his pivotal position to serve his own interests, play his own game—make his own map. An agent of neither West nor East but, more than anything, an agent of chaos.

By the end of the war, Philby would take the game to an even more dizzying level of complexity and power. By 1945, he had engineered a spectacular coup within M.I.6 that got himself promoted to head of the newly created Russian section. He was then the man simultaneously responsible for telling the Brits what Stalin thought and telling Stalin what the Brits thought. In this unique Janus-faced position at this critical moment, he was perhaps the ultimate intelligence player, a key conceptual map maker of the postwar world, perfectly placed to make the colossi of East and West dance to his tune.

This is not the only interpretation of the Philby enigma, of course. There are still those who come forward to say that Kim Philby was really dancing to their tune—that Philby was “as much pawn as player.”

Some die-hard supporters of James Angleton, for instance, claim he was playing a “deep game” with Philby all along, deliberately feeding him disinformation—a proposition vigorously denied to me by the mole war historian of the C.I.A., Cleveland Cram, one of the few men who’ve read every single secret C.I.A. file on Philby, even those the agency denies exist.

And Cave Brown’s forthcoming biography entertains a provocative variant on the Philby-as-pawn hypothesis, that Philby was used by “C”—Sir Stewart Menzies, the legendary head of the wartime Secret Intelligence Service—to play disinformation games with the Soviets during the war (a fact reported by none other than the former C.I.A. head Allen Dulles). And that “C,” knowing of Philby’s early Communist background, may have known about, and used, Philby’s relation with the Russian intelligence services for his own “deep game,” a game that may have been played out even after Philby arrived in Moscow.

Support for this seemingly far-fetched triple-agent hypothesis, the one that triggered Graham Greene’s deathbed summons for his Philby papers, comes from an unexpected source. The newly opened K.G.B. files on Philby reveal that at least some elements in the K.G.B. were as paranoid about Philby’s all-powerful, unfathomable deceptiveness as James Angleton was.

Cave Brown’s manuscript quotes at length one senior K.G.B. colleague of Philby’s, Mikhail Petrovich Lyubimov, formerly of the K.G.B.’s British section:

“When I read Kim’s files to prepare myself for work as the deputy chief of the British Section, I found a big document, about 25 typewritten pages, dated about 1948, signed by the head of the British Department, Madame Modrjkskaj, who analyzed the work of Philby, Maclean and Burgess. And she came to the conclusion that Kim was a plant of the M.I.6 working very actively and in a very subtle British way. The deputy chief of Smersh [editor’s note: an organization comprised of three Russian counter-intelligence organization], General Leonid Reichman, a friend of mine and of my father, told me only four years ago: ‘I am sure that [Philby, Burgess and Maclean] were British spies.’ ”

Just how subtle was Kim Philby? Could he have been a British spy when he arrived in Moscow? Those who argue the case—on both sides—focus on one of the single most mystery-shrouded episodes in the whole Philby saga: the moment in Beirut when he was literally between two worlds. The moment in 1963 when one of his closest Secret Service colleagues confronted him with evidence that he was a Soviet agent in a dramatic, face-to-face showdown. The showdown that resulted in Philby first confessing and then double-crossing his confessor by slipping out of Beirut to the safety of Moscow.

Windows Into the Soul

London, 1994. The old spy was dying fast. His breath was coming in gasps over the phone. In three days he would be dead. This was, I believe, the last interview he gave. He couldn’t talk for long, he told me, but there were still some things he wanted to say about Kim Philby, some myths he wanted to put to rest. He was still haunted by Philby. Still plagued by the rumors and whispers about his showdown with Philby that night in Beirut in 1963.

The dying spy was not the only one haunted. The events of that night in Beirut have plagued and disrupted the spy establishments of the United Kingdom for the past quarter century—Kim Philby’s parting black valentine to those he betrayed. The belief that Philby was tipped off to the coming confrontation, that the “confession” he gave was an artful sham, disinformation designed to buy time to execute his escape plan—a belief still held by many in the spy business—was directly responsible for the 20-year-long mole hunt in Britain that culminated in the famous Spycatcher controversy.

“It’s nonsense,” the dying spy insisted to me. Philby was not tipped off he was about to be confronted. Philby walked into it unawares. “He wasn’t ready at all. He was simply asked to come to an apartment by his [M.I.6] contact in Beirut. He didn’t know who he was going to meet. Instead of finding our man in Beirut, he found me.”

The man Philby found, the spy speaking to me, was Nicholas Elliott, the perfect embodiment of the blue-blood, playing-fields-of-Eton establishment Philby arose from and betrayed. After serving in a number of top M.I.6 posts, he eventually became Margaret Thatcher’s personal intelligence adviser on Soviet affairs. A cultivated bon vivant who also reportedly possessed an inexhaustible store of filthy jokes, Elliott had become close to Philby during their wartime service in M.I.6. So close, in fact, that at one time Philby disclosed something to Elliott he’d disclosed to no one else—the shattering secret of his marital life. A secret that (Elliott argues in his memoirs) revealed that “the arch-deceiver had himself been deceived, the arch-liar had been tricked for so many years.”

It wasn’t sexual infidelity. Rather it was his wife’s failure to confide the nature of the secret life she was living—and Philby’s 10-year failure to penetrate her deception.

In 1948, Aileen (second of his four wives) came down with the latest in a succession of mysterious illnesses. Philby begged his friend Nicholas Elliott, then M.I.6 station chief in Bern, to find a Swiss doctor who could get to the bottom of Aileen’s problem. After flying Aileen to Bern for treatment, Philby was devastated to learn from a psychologist there that ever since her teens, Aileen had been afflicted with a severe compulsive disorder that caused her to cut and mutilate herself and to inject herself with her own urine.

“It was an intense affront to Philby’s pride,” Elliott writes, that his wife had been able to hide a secret self from him.

Perhaps the fact that Elliott had that glimpse of the deceiver deceived explains Philby’s peculiar conduct toward him in that Beirut showdown in 1963.

In describing that moment in Beirut to me, Elliott was at great pains to insist that he was in command. In the last year of his life, controversy over the Philby confession had broken out anew in The London Times’s letters column; Elliott had been accused of “bungling” the job.

Elliott insisted to me he had taken Philby by surprise and that Philby was “shaken.”

“Very simply, I told him, ‘I know you’re a traitor and you’d better admit it, if you’re as intelligent as I think you are.’ ” Elliott said. “ ‘And we’ll both try to work something out.’ ”

Elliott offered Philby full immunity from prosecution, if he’d return to England and provide the intelligence services with a complete damage assessment—a deal similar to the one that would later be accepted by Philby’s fellow “Ring of Five” mole, Anthony Blunt. “That was the point of it all—the damage assessment,” Elliott told me.

Philby later told Phillip Knightley, his most famous biographer, that the deal had been unacceptable to him. Because it would have involved naming names—other K.G.B. moles—“that was no deal at all.” But Elliott contended to me that Philby had, in fact, accepted the deal. Elliott believed then, and continued to believe till the end of his life, that Philby had been ready to give up and go home.

Of course, it didn’t happen that way. Philby returned with a typewritten confession and then asked for more time to arrange his affairs. Elliott returned to London with the confession, apparently trusting Philby to keep his word about coming home. Philby instead chose another home. Within a week, he’d disappeared from Beirut and, before long, showed up in Moscow, mocking the men he’d betrayed.

From out of the murk of this exceedingly murky episode have emerged several conflicting theories of what was really going on:

1. Philby had cracked: Tired and shamed by Elliott, he wanted to accept the deal and go back to Britain. But, Elliott told me, when the K.G.B. learned of what had gone on between him and Philby, “it caused consternation” and Philby practically had to be kidnapped at gunpoint and shanghaied off to Moscow.

2. Then there are those, like the author of Spycatcher, Peter Wright, and the espionage historian Nigel West, who think Philby was tipped off by a highly placed British mole and his “confession” was all an artful con, Elliott a gull for believing him. (Former Secret Service mole hunter Wright’s obsessive search for the man who tipped off Philby spread the same kind of suspicion and paranoia that Angleton’s mole hunt did in the C.I.A—which might have been Philby’s objective in hinting to Elliott that he had been warned.)

3. A third school argues that Elliott’s real mission was not to persuade Philby to come back home to England at all but to pointedly hint Philby would be better off if he repaired to Moscow, sparing his old colleagues the embarrassing prospect of Philby at large in the United Kingdom, free to broadcast humiliating details of his successes in conning everyone.

4. Finally, there is an even more conspiratorial school that believes it was at this point that Elliott “turned” Philby from Soviet double to British triple agent and that the whole confrontation had been nothing but a charade to convince the K.G.B. that Philby had to be brought back to Moscow, where he could serve as a British penetration of Moscow Center.

In the course of my odyssey through the Philbian cosmos, I came upon two extraordinary documents that throw new light on this mysterious episode.

The first is a memo that contains a purported account of a confession about Philby’s confession. A purported account of Nicholas Elliott’s deathbed confession about that Beirut encounter—the notional shrive.

It contends that sometime in the 72 hours between the time I spoke to him and his death, Nicholas Elliott was “shriven”—his confession was taken according to the rites of the Anglican church. What is said in a shrive is meant to be between the dying man, his confessor and his God.

The memo on the alleged shrive was sent to me by E. J. Applewhite, the C.I.A. station chief in Beirut during Philby’s last days there. It records Applewhite’s conversation with a spook in London whose name Applewhite has blotted out in the copy he sent to me.

The memo, entitled “Elliott and Philby Confrontation,” begins as follows:

“[Name blotted out] says he has learned from several old hands from his tour in the U.K. that, shortly before Nicholas Elliott died in London of cancer of the liver, Elliott was ‘shriven’ by one Canon Pilkington. The Canon was on the point of telling [the] informant the nature of Elliott’s final confession, but he was interrupted. The informant said no matter: I know what Nick’s confession would have been—that in that final climactic confrontation with Philby in Beirut, the dictates of patriotism and duty were strained to the breaking point by bonds of friendship and class loyalty to Philby, and that in the event it was Elliott’s great lapse that he had tipped Philby off and had ‘permitted him to fly the coop.’ That was what was weighing on the Elliott conscience.”

Applewhite, distancing himself from the informant’s story, calls it “an oversimplification.” But I think it’s more than that. It sounds to me like a sophisticated disinformation operation on the part of the informant, one worthy of Kim Philby himself.

Note that the “informant” tries to give the impression that Canon Pilkington betrayed the sanctity of the confession, when in fact the informant only conjectures what the Canon might have told him, had he not been “interrupted.” And, in fact, when I reached Canon Pilkington, he denounced the story colorfully as “a load of codswallop.” Pilkington said he and Elliott had had “a few words” on the subject of Philby, but that there was no formal shrive and no deathbed remorse about Philby.

Who might have been the source of the disinformation? I’d suggest it’s a manifestation of the undying bitterness over the Philby affair between the gumshoes of M.I.5 (the British equivalent of our F.B.I.) and the old-school-tie aristocrats of M.I.6, who were thought to have protected Philby as one of their own.

What’s shocking here is the lengths to which the partisans in the never-ending Philby wars will go: a notional version of a dying man’s final rites is used to accuse him of collaborating in the escape of a traitor.

Still, there was something about that confession drama in Beirut that tormented Elliott until the end. And if it did weigh on Elliott’s conscience, might it also have weighed on Philby’s? Did Kim Philby have a conscience?

Here the second revealing document to surface has particular relevance—a memorandum in Philby’s own handwriting that I found myself fixated on while going through the Philby papers in Sotheby’s London offices. If espionage, as defined by Sir Francis Walsingham, the 16th-century founder of the British Secret Service, is the effort to “find windows into men’s souls,” I found this document to be, if not a window into Philby’s soul, then a glimpse of his own chilling soullessness.

It’s a nine-page memorandum in Philby’s tiny, precise handwriting, a memo that seems to have escaped the K.G.B. sweep of his apartment after his death. (His wife, Rufina, claims it only recently turned up, perhaps stuck in the back of a file drawer.) As such, it may be the only manuscript from Philby’s Moscow years not read, pored over and vetted by his suspicious spymasters. All we have of the uncensored Philby.

The subject of the memo is one that was obviously close to Philby’s heart: the psychology of interrogation and confession; how a spy should behave when he’s confronted and accused of treason. The memo seems to have been drafted for a K.G.B. training course for agent handlers. But it also may have been Philby’s indirect way of confronting K.G.B. suspicions about his behavior in Beirut.

Philby opens the memo with a “syllogism” on confessions:

1. “Giving information to the enemy is always wrong.

2. “Confession is giving information to the enemy.

3. “Therefore, confession is wrong.”

This is a pretty audacious ploy. After all, Philby himself had supposedly confessed—he certainly gave some kind of information to the enemy, his friend Nicholas Elliott. Was it all disinformation and black valentines? Could the K.G.B. be sure? It seems possible Philby is attempting to counter suspicion of him with this syllogism:

—Philby says all confession is wrong.

—Therefore, Philby could not have (really) confessed.

Whatever the ulterior purpose of Philby’s syllogism on confession, something else emerges in the remainder of the nine-page memo, the painstaking analysis he devotes to the interrogation-confession dramas of two K.G.B. atom spies of the late ’40’s, Klaus Fuchs and Alan Nunn May, who faced the same kind of tense inquisitions Philby had but who cracked under pressure.

With the eye of an expert who’s seen such battles of will, both as interrogator and suspect, Philby takes us inside the give-and-take of the atom spy confrontations and concludes that in both cases the seemingly confident interrogators were actually in a desperately weak position. They knew that the sort of evidence they had was either too vague or too explosively secret to be used in court.

The interrogators were therefore “bluffing desperately,” Philby says, and the suspects were in a far stronger position than they knew: if they had held out and refused to confess, “they’d have remained free men.”

Free men! His use of the term is doubly ironic. He’d just enumerated all the obstacles the interrogators faced from the due-process, civil-liberties protections afforded by Western democracies—the right to a public trial, to confront accusers, to the protection against self-incrimination that shielded the suspected spies from the tortured “confessions” and summary executions the Soviet system routinely used for those suspected of treachery.

I found something particularly repellent about Philby’s smug dissection of the weaknesses of Western interrogators, inhibited by the protections afforded the weak and the underdog—something almost willfully unconscious. Why, one wants to ask him, dedicate oneself to destroying this system, for the sake of one that he knew had arbitrarily murdered its most naively idealistic operatives on the basis of mere suspicion?

Philby writers often cite the doggerel verse from [Rudyard] Kipling’s Kim about the qualifications of a successful spy, as a way of explaining this kind of moral schizophrenia:

Something I owe to the soil that grew—

More to the life that fed—

But most to Allah, Who gave me two

Separate sides to my head.

But schizophrenia doesn’t really explain Philby so much as excuse him. The disease metaphor suggests he was a victim and not responsible for his thought processes and the acts that grew out of them. Unfortunately—in some cases, unforgivably—he was.

The Great Pretender

The former spy was talking about Kim Philby’s love letters. His courtship style. He was attempting to counter a tale told by another spy suggesting that Philby was bisexual.

No, this spy said, that wasn’t Philby. He’d never thought Philby was homosexual, he insisted, but there was something peculiar about the nature of his heterosexuality, something that revealed itself in his love talk.

“What I never understood is the way he used language,” the former spy said. “He would describe himself as deeply, utterly devoted from almost the first moment, as if the last woman had never existed, even though he’d professed himself deeply, eternally devoted to her. Those letters to Eleanor.”

Eleanor Brewer was the married woman Philby wooed away from her husband, a New York Times correspondent in Beirut. In The Master Spy, his book on Philby, Phillip Knightley describes the “tiny love letters written on paper taken from cigarette boxes,” which Philby would send to Eleanor several times a day:

“Deeper in love than ever, my darling….”

XXX from your Kim

To be followed later the same day by;

“Deeper and deeper my darling….”

XXX from your Kim

Of course, it was more than just little love notes that won Philby the affection—and, amazingly, the enduring loyalty—of his women. In The Spy I Loved, Eleanor’s memoir of their affair, their marriage and her brief sojourn in Moscow with Philby (before he left her to take up with Melinda Maclean), Eleanor describes her first impressions of Philby in Beirut: “His eyes were an intense blue. I thought that here was a man who had seen a lot of the world, who was experienced, and yet who seemed to have suffered…. He had a gift for creating an atmosphere of such intimacy that I found myself talking freely to him. I was very impressed by his beautiful manners.”

Many men, as well, found themselves “talking freely to him,” much to their regret. For Philby, intimacy was his special espionage talent.

When the former spy finished his disquisition on Philby’s all-or-nothing-at-all love rhetoric, I asked him if he thought there was an analogy between the kind of near-religious conversion experiences Philby underwent in his romantic life and the blind romanticism of his ideological conversion.

He smiled and asked me, “What do you think?”

It may strain the analogy a bit, but after a lifelong romantic affair with the image, the fantasy of Soviet Communism, Moscow was still a mail-order bride for Philby until he came face to face with her in 1963.

Up until then, he’d enjoyed the best of both worlds. He could wallow in decadent bourgeois freedoms while maintaining a surreptitious self-righteous superiority over others who did, keeping pure his devotion to the promised bride. Then, in 1963, after his flight from Beirut, he arrived in Moscow and saw with his own eyes the ugly reality of the love object he’d worshipped from afar.

Not just the grim, disillusioning reality of Soviet life, but the shocking truth about his own status in the organization he’d dedicated his life to, the K.G.B. “They destroyed him,” the former K.G.B. man told me over the phone from Moscow. The man speaking, Mikhail Lyubimov, was among Philby’s closest K.G.B. colleagues, the one who perhaps knew him best, the one with whom Philby shared the depths of disenchantment and doubt he’d successfully concealed from journalists and friends in the West up until the moment of his death.

Before speaking to Lyubimov, I’d listened to some 20 hours of tapes made in Moscow by Cave Brown. Tapes, for the most part, of interviews with key figures in the K.G.B. orbit around Philby’s apartment on Patriarch’s Pond in Moscow, men who’d shared his hospitality, his secrets and his doubts.

It’s astonishing at first to hear these men, once possessors of the most closely guarded secrets of the century—the secrets of the inner sanctum of the K.G.B., secrets men were murdered for knowing or seeking to know—discussing them so freely, so offhandedly with a journalist. Astonishing to hear these men casually dissecting the Philby persona.

One can hear in their voices different degrees of affection, admiration, sadness and anger at the treatment of this man, who had come to be such a highly charged symbol. But the common thread running through all their memories and reflections about Philby was deception.

Not deception in the sense of the grand game of global psych-out that Philby’s enemies envisioned him playing. “This is rubbish!” Lyubimov told me. It’s a judgment former K.G.B Gen. Oleg Kalugin (Philby’s boss in Moscow from 1970 to 1980) concurs in on Cave Brown’s tapes. It’s also one that the writings of Oleg Gordievsky, the British mole within the K.G.B., reflect: Philby wasn’t running deception operations in Moscow. He was the victim of one, of a Soviet deception about the kind of life he’d be leading once he came in from the cold.

According to Lyubimov, this deception began in Beirut just before his escape to Moscow. While Philby was weaving a web of deceit around Nicholas Elliott, he was unaware of the one being woven for him. “When he was leaving Beirut, he was told he would be in Lubyanka,” Lyubimov told me, referring to the Lubyanka headquarters building of the K.G.B., not the infamous prison in the basement known also by that name.

Others have reported that Philby expected to be made a K.G.B. general, that he expected to be named head of the K.G.B.’s England division. But, in fact, when he arrived, he found he’d been deceived in several ways: he was told that he was not and never would be a K.G.B. officer of any kind; rather he was an “agent,” a hireling—a lack of respect that never ceased to rankle him.

Not only didn’t Philby get a rank, even more humiliating, he didn’t even get an office.

“Any normal man who’d accomplished the feats Philby had would think he’d get his own study, his own telephone, a desk,” Lyubimov told me. “It never happened. Nothing happened. He became a sort of a little beggar somewhere in a little apartment. It was three rooms but very small.”

In fact, Philby’s first seven years in the Soviet Union were almost a form of house arrest. Again a victim of deception: “The K.G.B. told him they were afraid the British M.I.6 was going to try to assassinate him, so he had to have guards all the time, close surveillance,” Lyubimov said.

But the real reason was the Soviets didn’t completely trust him not to bolt for home. “They were afraid something would happen. And he would end up back in Britain or even America.”

“Did he know they didn’t trust him?”

“Oh yes, he knew.”

But it didn’t take long after he arrived in the Soviet Union for Philby to realize he’d been the victim of another kind of deception, an even more profound one.

From the first, he felt “a complete disillusionment from Soviet reality,” Lyubimov says. “He saw all the defects, the people who are afraid of everything. That had nothing to do with any Communism or Marxism which he had a perception of.”

The Marxism that Philby “had a perception of” before his arrival was a variety Lyubimov characterizes as “the romantic Marxism of the Comintern agents of the 1930’s.” Of the daring “illegals,” like the sexologist Deutsch, who thought of themselves as fighting Fascism for the sake of the future but rarely had to endure the reality of the future as it was embodied in Stalinist rule—until Stalin brought them back to be murdered in the Purges.

The reality of Brezhnev’s Russia, with its slow-motion Stalinism, was deeply demoralizing to Philby. According to several of the K.G.B. men Cave Brown interviewed, Philby was often dangerously outspoken in his open contempt for the Brezhnev regime. But was this because Philby was morally outraged by the system or because he wasn’t given the place in it he thought he deserved?

Lyubimov, who tends to romanticize Philby, believes his distress was genuine. “The idea of the absence of freedom—he couldn’t understand it,” Lyubimov told me. “He began to see it with how they treated Solzhenitsyn—which he called disgusting. That was the beginning of his dissidency. Once we had a quarrel about the treatment of writers. Kim was shouting, ‘Who is responsible?’ And I was saying: ‘Well it’s not my department [of the K.G.B.]. I’m not responsible.’ And he said: ‘No! You are responsible! We are all responsible.’ ”

Kim Philby dissident? Cave Brown tends to believe, based on his conversations with the former K.G.B. men around Philby, that he may have played a role with other liberal elements of the K.G.B. in making Gorbachev’s success possible. He suggests that Margaret Thatcher’s early embrace of Gorbachev in 1984 (“We can do business together”) might even have been prompted by information about Gorbachev’s intentions passed to her Soviet affairs adviser, Nicholas Elliott, by Philby—through Graham Greene’s British intelligence contacts. Cave Brown advances the argument that, toward the end of his life, Philby was seeking “redemption”—that fostering a Thatcher-Gorbachev rapprochement might have been the means for a reconciliation with the England he betrayed.

Cave Brown hedges his bets on whether Philby was doing so on behalf of his homeland, as an actual British triple agent, on behalf of reformist factions in the Soviet Union or on behalf of himself. The perennial Philby mystery again.

My belief is that while Philby may have hedged his bets in some ways, it’s unlikely he was a triple agent. Indeed, he was extremely sensitive about being called even a double agent. Hated it, in fact. The way he saw it, a double agent betrays one master for another, while he, Philby, had only one master all along: the Soviet Union. He had no loyalty to the Brits to betray.

But I also believe Philby was engaged in an elaborate and desperate deception operation during his Moscow years, his last great intelligence operation. This was his campaign to conceal from those in the West just how badly he’d been deceived about the Soviet system.

One thing we learn from a study of Philby’s Moscow years is that for all his contempt for the capitalist world, he had a pronounced, even unseemly, eagerness to be respected by the West, particularly by his fellow Brits. One thing he was not going to do was give them the satisfaction of seeing how badly the betrayer had been betrayed. Not while he was alive.

“He had a natural desire to have a pretense, to have a facade,” Lyubimov told me.

The counterdeception-disinformation operation began with Philby’s book My Silent War, a masterpiece of overstatement through deceptive understatement. In it, Philby created a picture of himself as a cool, daring, nerveless, unflappable operator, who used only the driest deadpan understatement to describe his hairbreadth escapes, ingenious stratagems and clandestine coups. The conspicuous absence of boasting accomplished what boasting itself could not. And along with casually dropped references to “my comrades,” his unfailingly brilliant and loyal K.G.B. collaborators, he painted a portrait of espionage superheroes, a team that had accomplished far more than he could ever speak about.

The truth was, he really wasn’t on the team at all any more. Occasionally, the K.G.B. took pity on him, because it looked as though he was drinking himself to death in his despair, and gave him some quasi-operational tasks. For a few years, he taught an informal seminar on England to fledgling K.G.B. officers about to depart for Albion to try to recruit the next generation of Philbys.

Still, there was at least one instance when Philby’s talents were brought into play. In the late 70’s, Philby, who never lost his nose for sniffing out a mole, was called in to assess a K.G.B. intelligence disaster in Norway, a key agent blown. Given a sanitized version of the files to analyze, Philby contended he knew what went wrong: the Brits must have a mole in the K.G.B. who blew the cover of the Norway agent. In fact, he turned out to be right. There really was a high-level mole in the K.G.B., Oleg Gordievsky, although the Soviets were unable to pinpoint him until years later when, Gordievsky believes, Aldrich Ames provided information that clinched the case. Gordievsky barely escaped with his life.

But for the most part, Philby was frozen out, his suggestions ignored. “The K.G.B. was too stupid and impotent to make use of him,” Lyubimov reiterated to me. “This destroyed him. This ruined his life.”

And, in fact, the book My Silent War, which had been one of the chief vehicles of Philby’s deception of the West, became one of the chief instruments of torture the K.G.B. used against him. Philby desperately wanted the book, which came out in 1968 in the West, to be published in the Soviet Union—to give him the heroic status with the Soviet public his vanity thought he’d earned.

“All this time, he wanted to be a hero of this country,” Lyubimov says. “But they did everything to prevent him from this.”

It took 12 years of delays, of brutal editing, of bad translations for Philby to get a mutilated version of My Silent War into print in Russian.

And even then, Lyubimov says, “It wasn’t really published. A little edition, just distributed to the Central Committee, the military.” It was, adds Lyubimov, “almost a confidential publication. He was killed by this.”

And yet you wouldn’t know it from the way Philby bragged about his book to Phillip Knightley in 1988: “It was an enormous success and sold more than 200,000 copies. The trouble was that I hadn’t foreseen that it would sell so well. It was only in the bookshops a few days and then it was gone. So I didn’t get enough copies for myself.”

This is fairly pathetic, but at times Philby’s desperation to be thought of as a success by his British peers reaches comedic levels. To Knightley, he described his Order of Lenin decoration as comparable to “one of the better K’s” (degrees of knighthood), sounding like a pseud out of Evelyn Waugh.

And there was one point at which Philby’s image-building campaign seemed to go beyond deception to an astonishing level of self-deception. The former C.I.A chief Richard Helms is fond of telling a story about an exchange between Philby and an American reporter in Moscow. The reporter told of a projected film about his life. Philby asked who was going to play him.

“Michael York,” replied the reporter.

Philby recoiled, as if slapped. “But he’s not a gentleman,” he said.

Perhaps the single most telling instance of Philby’s last great disinformation operation can be found in correspondence between him and Graham Greene over Greene’s novel The Human Factor. It was a book Greene wrote in the ’60’s but didn’t publish until the late ’70’s because it came so close to the Philby affair.

Many found resemblances to Philby and his predicament in Greene’s protagonist, a mid-level mole named Castle. Apparently, Philby did too. Greene had sent him a copy of the manuscript before publication, and Philby had made particular objection to one passage, at the very close of the book, when Castle, like Philby, has escaped to Moscow and is trying to adjust to his ambiguous position there.

The passage Philby objected to depicts Castle in a tiny, depressing apartment, amid stained, secondhand furniture, insisting over his malfunctioning telephone to his wife in London, that he’s quite content: “Oh, everyone is very kind. They have given me a sort of job. They are grateful to me …. ”

Philby wrote to Greene urging him to change this impression. It was misleading, melancholy. And, by implication, not at all like his circumstances in Moscow. Greene wrote back thanking Philby for the helpful suggestion, but he would not change the bleak mood.

Greene must have had the novelist’s sixth sense from this exchange that the melancholy portrait of the lonely mole in his Moscow apartment, vainly boasting how “grateful” everyone was, had struck home with Philby. That there was a truth to it Philby recognized, a truth about himself that all the tacky ribbons and trophies he gathered from his “grateful” fraternal K.G.B. comrades could not obscure.

Shortly after Graham Greene’s funeral, his biographer, Norman Sherry, visited the room where Greene had died. On a table next to the empty bed, he found the letter he’d written to Greene, the one asking for his final thoughts on Philby.

Members of Greene’s family said that they had found no reply.

If Greene took a Philby secret to his grave, it might have had nothing to do with whether Kim was a double or triple agent. It might have had everything to do with the lonely man in the Moscow apartment.

Perhaps Greene saw through Philby’s last great lie, but—unlike Kim—he wouldn’t blow a friend’s cover.

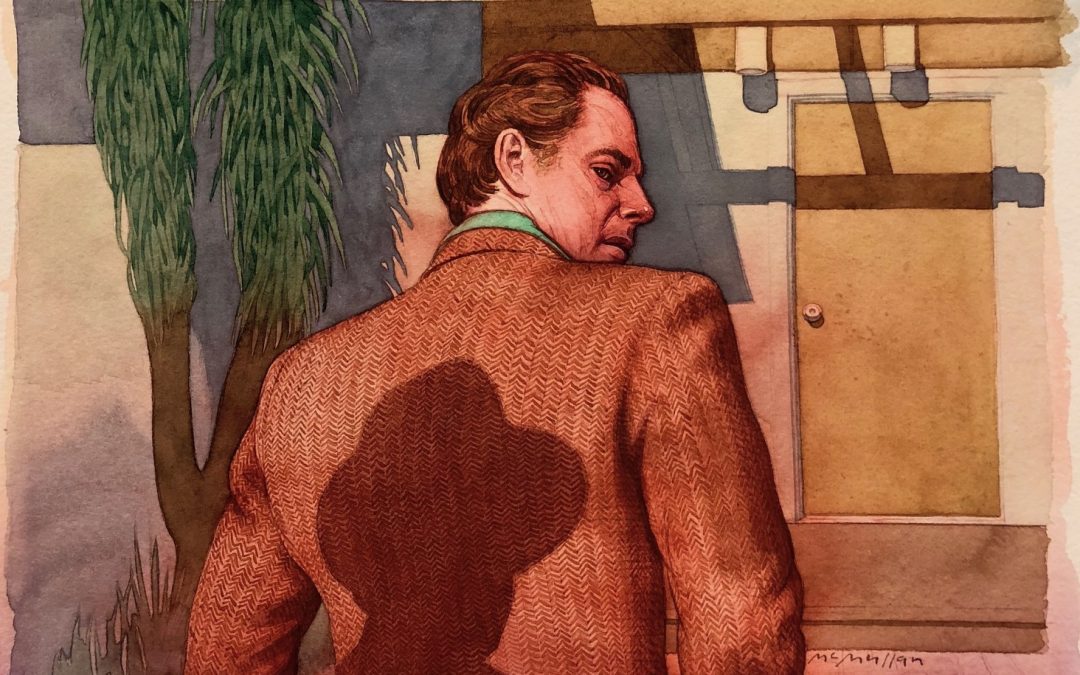

[Illustration by James McMullan]