Harry Ritz will say it himself, but he prefers that others say it for him.

“As far as I’m concerned,” says Mel Brooks, “Harry Ritz was the funniest man ever. His craziness and his freedom were unmatched. There was no intellectualizing with him. You just hoped there were no pointy objects in the room when he was working ’cause you were down on the floor, spitting, out of control, laughing your brains out. Harry Ritz always put me away. Always.”

“This man gave comedy a whole new dimension,” says Sid Caesar. “Harry was the great innovator. His energy and his sensibility opened things up for all of us. He had to be the funniest man of his time.”

“Harry was the teacher,” says Jerry Lewis. “He had the extraordinary ability to deny himself dignity onstage. Harry taught us that the only thing that mattered was getting a laugh—whether you did it with a camel or with two rabbis humping a road map. Harry spawned us all. We all begged, borrowed and stole from him, every one of us. Without him, we wouldn’t be here.”

Almost to a man, comics adore Harry Ritz; they tirelessly tell stories about him, they dissect his style, they imitate his routines. If the world was made up of comedians, Harry Ritz would be the biggest star you ever saw.

But it isn’t, and he’s not. The recognition Harry did receive—as the top banana among the three Ritz Brothers—was relatively scant and short-lived. During his heyday, in the late Thirties and early Forties, his particular brand of comedy was not thought of as art, and when it came time to list the immortals of that period, no one thought to include Harry’s name among them. Today, thirty-three years after the Ritz Brothers starred in their last feature film, it is very difficult to find anyone under the age of forty who has even heard of them.

Which says a good deal about the impermanence of it all, because there was a time when it was impossible to avoid the Ritz Brothers. Between 1934 and 1943, they turned out fifteen features and three shorts; they also performed in theaters and clubs. Before a contract dispute with Darryl Zanuck ended what had been a mutually beneficial relationship, they were the comedy kings of the Twentieth Century-Fox lot, hauling down $7,500 a week.

The Ritzes were what Jan Murray calls “tumult” comedians. Subtle they weren’t. There was always a lot of running around in their routines, and loud noises, and rolling of eyes, and gags about homosexuals and busty women. They were masters of movement and, in addition to dances so extraordinarily well-timed that the three of them looked as if they were seven together, they were capable of a dozen comic walks and runs.

Harry was the funniest of the Ritz Brothers. He rolled his eyes better than the other two, and walked funnier, and did funnier pratfalls. It often looked as if his brothers’ prime function was to set up business for Harry.

For those not attuned to such things, it was easy to dismiss all of this as lowbrow nonsense, crude and obvious. But others saw the Ritzes’ choreographed chaos as inspired. Sure, their partisans acknowledged, a lot of comedians ran around and acted crazy, but no one else did it with quite the same joy, the same abandon, the same self-satisfied mindlessness. The Ritz Brothers, they insisted, were funnier than anyone.

And Harry was the funniest of the Ritz Brothers. There was no doubt about that. Though theirs was ensemble comedy—they almost always dressed the same and were generally indistinguishable as characters— Harry, the one in the middle, always had the most to do. He rolled his eyes better than the other two, and walked funnier, and did funnier pratfalls. Indeed, it often looked as if his brothers’ prime function was to set up business for Harry.

Harry so obviously dominated the act that the other two made light of it onstage, one of them suggesting that the trio should be renamed “The Ritz Brother and His Two Brothers.” Al and Jimmy, the brothers, later began singing a mock-bitter song, directed at Harry, entitled The Guy in the Middle:

“The guy in the middle/ we hear people say/ the guy in the middle is the funny one/The other two/ the other two are just a pair of bums/ One belongs in a penthouse/ the other two belong in the slums”

The definition of a rotten agent, went one Hollywood joke thirty years ago, was one who handled all the Ritz Brothers except Harry.

Harry, people in the business knew, dominated the act offstage as well as on. He created most of their best routines and staged their dance numbers. It was his imagination, as much as his elastic face and spindly legs, that kept the act going.

Indeed, some of the bits of business Harry created were so strong that they have survived wholly independent of the Ritz Brothers. There’s a guy in New York, a small-time impressionist named Will Jordan, who can go on for twenty minutes, ticking off the shtick others have appropriated from Harry: Danny Kaye’s Russian gibberish, Milton Berle’s way of walking on his ankles, Jerry Lewis’ crossed eyes and dumb look, Jackie Gleason’s “And away we go” walk, everyone’s German professor. Then, too, there are pieces of Ritz Brothers madness in the films of Mel Brooks, Gene Wilder and Woody Allen. The notion of a nervous sperm waiting to be launched into God knows where, for instance, later used so successfully in Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex…., was a Ritz original.

None of that ever bothered Harry, who took it as flattery. He didn’t complain when others, using his material, started playing better clubs for more money. Through the late Forties, the Fifties and on into the Sixties, the Ritzes went blithely along their way, performing regularly, satisfied to be making more than enough to get by. Occasionally they did a guest spot on television, but mostly they stuck to clubs, where they had a dwindling—but rabidly faithful— following.

Then, one evening in December, 1965, during an engagement at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, Al, the oldest of the brothers, collapsed and died of a heart attack. Harry and Jimmy were shattered, but six months later they regrouped and tried to make it as a duo. Though their material was essentially unchanged, the act just wasn’t the same; the remaining Ritz Brothers worked only sporadically.

Jimmy now lives in semi-retirement in L.A., but Harry, at sixty-nine, is still plugging. Several years ago he moved his family from Beverly Hills to Las Vegas, the live-entertainment capital of the world. It hasn’t helped. Though Vegas is the place where performers like Wayne Newton and John Davidson are paid upwards of $100,000 a week, where comedians like Rip Taylor and Corbett Monica, not to mention a hundred stand-up types whom Mel Brooks dismisses collectively as “Jackie Jackie,” work regularly, Harry Ritz has not had an offer to play the town in five years.

But you won’t hear about it from Harry Ritz. “Oh, no,” he says, striding through the Caesars Palace casino en route to the lounge, “I’m doing great. I work when I want, maybe eight or ten weeks a year. I do a lot of benefits. They’ll call and say, ‘Harry, c’mon over. Get me crazy Harry,’ and I go.”

Harry speaks loudly to make himself heard above the clatter of the roulette wheels and the shouts of the craps players. None of the gamblers seems to recognize the trim, still youthful comedian, hand in hand with his wife, as he moves by them. “I still got plenty of fans,” adds Harry.

They reach the lounge, Cleopatra’s Barge, a bank of small tables hard by the two-dollar blackjack area, and Harry, who, with his sharp features, well-groomed head of white hair and desert tan, looks like a Jewish version of Douglas Fairbanks Jr., pulls out a chair for his wife, Naomi. “Would you believe it,” he says admiringly, “this girl is only twenty-seven years old! Marry young to stay young.”

As a matter of fact, it is hard to believe. Naomi, who has blond hair, blue eyes, lots of glittery jewelry and startlingly bright red lips, is rather attractive, but she certainly doesn’t look twenty-seven.

“Oh, Harry,” she says, giving him a playful tap on the shoulder, “you know that’s not true.” They grin at each other. “I’m actually thirty-six,” she explains, turning away from him. “Harry tells people I’m twenty-seven because he wants me to be young.” She turns back to Harry and gives him a peck on the mouth. They giggle.

This, it turns out, is the way it is with Harry and Naomi. They are incessantly holding hands, constantly smooching, forever exchanging endearing little sentiments. Naomi is incredibly attentive to Harry’s needs, not only watching to see that he takes proper care of himself, but making sure his accomplishments get a full airing.

“Tell about the cruise,” she says now, picking up the thread of the conversation dropped a couple of minutes earlier.

“Yeah,” says Harry, “we just had a job last month, my brother and me. We worked a ship, the Fair Wind—five shows in twenty days for a fortune of money. Five big figures! We knocked the people dead. They weren’t young, between fifty and sixty-five, but they remembered us. We knocked ’em dead!”

His story completed, Harry falls silent. A waitress in a brief toga arrives, and they order a white wine for Naomi, a Coke for Harry. The silence continues a moment after she leaves until Harry breaks it. “We played here,” he says, indicating a large lounge, now a keno parlor, about twenty yards behind him. “It was called Nero’s Nook. We opened the place. They were dying to get us, had to pay us a fortune of money.” He pauses. “It was only a lounge,” he concedes, “but they paid us much more than the usual lounge act. Five big figures.”

“Harry brought show girls into this town for the first time,” says Naomi.

“Sure,” agrees Harry. “They thought I was crazy. The owner of the club said, ‘They don’t want girls here. Anyway, they’ll never allow it in Carson City.’ But I brought six girls down here from Reno and dressed ’em in shorts. Beautiful!”

“The town was really different then,” observes Naomi.

“Sure,” says Harry. “We were the first big act in Vegas, twenty-nine, thirty years ago. We were the first to get twenty-five grand a week when Bugsy Siegel opened the Flamingo. Nice guy. Good-looking boy. If we were playing here today, they’d have to pay us two hundred fifty thousand dollars a week. A quarter of a million bucks!”

“That’s a lot of money, my friend.”

Harry looks up, and a solidly built middle-aged guy in a grey suit claps a hand on his shoulder. It is Al Rosen, former infielder for the Cleveland Indians and now one of the official hosts for Caesars Palace. He smiles at Harry. “There will be no carrying on in my lounge, sir.”

“Just telling a few stories,” says Harry.

“Make ’em sweet,” says Rosen, “and not too dirty.” He moves on to another table.

“A great guy,” says Harry. “All the hosts here are great guys. Johnny Weissmuller, he loves me. I used to swim with him a lot. And Joe Louis! He sits with us every time we come in here.”

“One reason people like me is because I’m not cruel.”

It’s awfully hard to get a negative word about anyone out of Harry. Most of his stories have to do with how much he likes someone or how much other people like him. A variation on that theme has Harry going places, being recognized and being told how terrific he is. In rapid succession, he tells of some kids he met on a street in Vegas who reported they had arisen at six a.m. to catch one of his films on television; of an Italian family, owners of a restaurant in the Catskills, who wept with joy at his reappearance in their town after a fifty-year absence; of Fred Astaire’s telling a mutual friend how much he admires Harry’s dancing.

Harry recounts the stories in an even tone and without excessive hyperbole. They are obviously true and he sees no reason to feign humility. “One reason people like me,” he says at one point, “is because I’m not cruel. I used to do a bit about a deaf guy, but I’d never use it in a show. It’s not nice. You never know who might be sitting out there. I never did spastic walks for the same reason. I told Jerry Lewis years ago, ‘Maybe you shouldn’t do that stuff. You do muscular dystrophy so why do this?’ He cut it right out. He never did it anymore.”

Harry nods somberly in affirmation of what he has said. Then he pushes his chair from the table, slowly rises and straightens out his snappy crushed-velvet suit. “I’m going to the toilet.”

“It’s true,” says Naomi when he is gone. “Harry’s the original Mr. Nice Guy. He’s so sweet, he’s sometimes his own worst enemy. One time he had a Romanian cook whose cooking was so rich the doctor ordered him to stop eating it. But Harry couldn’t bring himself to fire her. Instead he pretended he had to move to Europe; he had Bekins come, pack everything in barrels and haul it away. The next day he took her to the train and had a big farewell scene. Then he called Bekins and had them bring everything back.”

She shakes her head. “And the way he lets people get away with lifting his material! Harry was the first one to roll his eyes—he even spells his name with his eyeballs—but suddenly everyone was doing it, on TV, in the movies….”

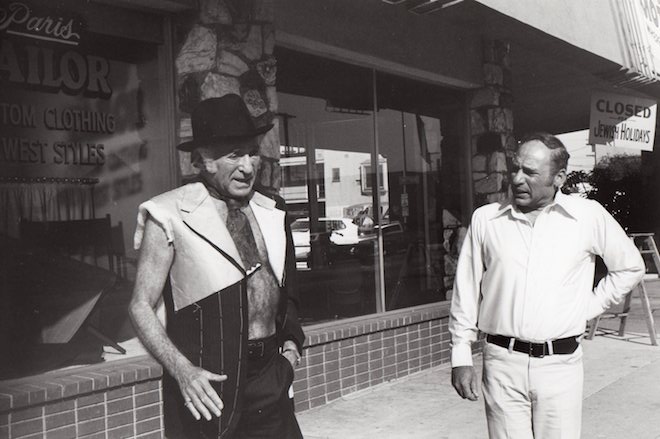

Harry, en route back to the table, has caught the last part of what Naomi is saying. “Mel did things with his eyes in Blazing Saddles,” he says, interrupting, “Ben Turpin–type stuff. Very funny.” He pauses. “He’s a very funny man. Loves me. I’m going to have a part in his new picture, Silent Movie. I’m going to be in a tailor-shop bit.”

Naomi takes his hand and gives it a squeeze. “My brother and I just shot a little thing out in Palm Springs they’re gonna call Blazing Stewardesses,” he continues. “We did seven or eight bits for this guy, trying to goose up his film a little.”

The opus in question is a dismal little picture, a rip-off of a soft-core smash called The Stewardesses, that was thrown together in a couple of weeks. Harry and Jimmy, featured as “Special Guest Stars,” appear randomly as comic relief, doing some of their old nightclub shtick. It took the producer of the film—who had originally planned to use the Three Stooges until, one by one, they died off on him—over two months to find the Ritzes. It seems that their agent, once one of the top men in the field but now past eighty and barely able to drive a car let alone a hard bargain, had neglected to list them with the Screen Actors Guild.

Harry, of course, would never consider getting a new agent. Instead, when the brothers were subsequently offered the chance to appear in a more respectable film, Paramount’s Won Ton Ton, he simply took charge of negotiations himself. “Yeah,” he is saying now, “this is a real big film. It’s about Hollywood in the Thirties, and they used about forty or fifty big stars. The problem was, they stuck most of ’em with thirty-second bits. Like Ricardo Montalban. He got really aggravated at what he did, felt he was selling himself cheap. He wasn’t the only one. There was Andy Devine, Mickey Rooney, Vic Mature—so many I can’t remember ’em all.”

He stops and pulls himself up ramrod straight. When he continues, it is with uncharacteristic intensity. “They only wanted to give us one line. I threw the script in the director’s face and said, ‘Take this and wipe your ass with it.’ And we made ’em back down. We wrote a whole scene for ourselves, as washerwomen, and after we shot it, everyone said it was the best thing in the picture. The crew stood up and applauded! Jack Carter says they oughta call the film ‘The Ritz Brothers in Won Ton Ton.’”

He sinks into his chair and mutters, “They can’t treat us that way!”

“Tell about the commercial,” prompts Naomi.

Harry straightens back up. “That’s right. One of the things we did in Won Ton Ton was our famous ‘Don’t holler’ bit. Jimmy starts screaming at me and I say—” he scrooches down, assumes the look of a miserably whipped cur and starts to whine—“‘Don’t holler. Please don’t holler.’ When the picture conies out, maybe we’ll get an Alka-Seltzer commercial out of it. Someone will say, ‘I told you not to eat so much and drink so much!’ and I’ll say, ‘Don’t holler.’”

Harry’s chances of doing the commercial will almost certainly be hurt by his insistence that his brother Jimmy be included in the package. During the course of his career, Harry has had literally hundreds of offers to perform as a single—Darryl Zanuck, for one, wanted to star him, minus Jimmy and Al, in films—and the consensus in the business is that had he gone that route he might have been the number-one comic in the country. But Harry wouldn’t hear of it. Even now he signs his autograph, “Harry Ritz (of the Ritz Bros).” “Listen,” he declares simply, “where I go, my brother goes.”

As it happens, one of the few Hollywood people of whom Harry speaks with less than wholehearted enthusiasm is Groucho Marx. “I like him,” he says a bit uneasily, “but you gotta catch him at the right moment.”

“C’mon,” urges Naomi, “there was no loyalty in that family.”

Harry smiles wanly. “Groucho was … I don’t know. Chico was a sweet guy, but he lost all his money gambling. Well, I just say if a brother’s down-and-out, you take care of him once in a while. Groucho made a lot of money—he’s still making money with that damn TV show of his with the duck—but he never helped. He ran around with a different crowd from his brothers. We guys did everything together. We were best friends.”

“That’s right,” says Naomi. “When we had the house in Beverly Hills, Jimmy was over five nights a week.”

“Of course,” adds Harry a moment later, “if the right part comes along, I suppose I would consider doing a picture alone. I mean, I read for the George Burns part in The Sunshine Boys. And for the Meyer Lansky role in Godfather II. That would’ve been fun to do. I know Meyer like a brother. He’s a very nice guy. Bugsy Siegel was also a great guy. Loved to have fun.”

“Hey gambardi,” he exclaims, “che serichi? La superletto vichi en perdo. Vuvo ma fellicia della getti.”

“Tell about the show you did for Capone,” says Naomi.

“Yeah,” says Harry, “we once did a show for Capone. We were playing the Oriental in Chicago, and one night after the show two of his boys, built like trucks, came over to us. Now we were pretty tough ourselves, from the roughest part of Brooklyn. I carried a switchblade with me everywhere until fifteen years ago. But these guys—” he waves his hand in a gesture of helplessness—“forget it. They said, ‘You meeta us outside at eleven-fifteen. We goa to Cicero to doa a show for Al.’ At eleven-fifteen they show up with two armored cars with machine guns everywhere. Jessel and Jolson were there that night, too. Nice guys, but they were sweating it out that night. You never saw such an audience. Capone applauded, they applauded. He laughed, they laughed. They didn’t know what we were doing, our material was so far above them.”

Harry smiles at the memory. “Hey,” he announces suddenly, “I haven’t done my Italian double-talk for a while!” With that, he is off, miraculously gibbering in Italian, though, in fact, he doesn’t speak a word of the language. “Hey gambardi,” he exclaims, “che serichi? La superletto vichi en perdo. Vuvo ma fellicia della getti.”

A moment later, without warning, he shifts gears and starts spouting phony French. “S’il vous plait,” he says, Gallic to the core, “senser le deuil. La patte pampee brise le mont, sans sasser la guasset. Fleur bébé de l’épace. La presse du belouse est sans tard.”

Naomi is rocking back and forth with laughter, and Harry is pleased as he can be with himself. “Sentré de l’imelle,” he exclaims, leaping to his feet. “Did you ever notice the way waiters used to walk at Lindy’s?” And there, in the lounge at Caesars Palace, he does his Lindy’s Waiters’ Walk, a flat-footed, bent-kneed, little-old-man’s shuffle. It is hilarious, perfect, and he knows it. He presses exuberantly on. In succession, Harry, agile as any twenty-year-old and as graceful as a prima ballerina, executes a series of dazzling comic walks and runs; he walks, leaning sharply forward as if into a stiff wind; he leans backward and kicks his legs straight out like a toy soldier; he walks jauntily ahead, abruptly stopping when he collides with an invisible wall ; he strides brusquely, determinedly forward, though his head is turned incongruously to the left and he cannot possibly have any idea where he is going; he runs with such frenetic vigor that he makes no forward progress whatsoever, managing only to kick himself repeatedly in the ass.

“Hey,” he asks, breathless, “you ever see a guy with seven afflictions walking down the street?” Without waiting for an answer, he launches into his pièce de résistance, a character beset by every imaginable physical embarrassment: he walks stiffly forward, his movements herky-jerky like some Rube Goldberg contraption, simultaneously limping, farting, tilting dangerously to one side, burping, twitching, wheezing and involuntarily shooting out an arm to the side. “Count ’em,” he says when he is through, “seven!”

But a moment later he is back in his chair; his joy has vanished as suddenly as it had arrived minutes earlier. “I’ve done most of those bits for forty years,” he says softly, “but there isn’t much call for them anymore.”

Naomi picks up his hand and kisses it. “The seven afflictions is my favorite,” she says.

“Yeah,” says Harry, “it’s a funny bit, isn’t it? But there’s no place to do that stuff anymore. I went back to the old studio when we were shooting Won Ton Ton, but it was all cut up. The beautiful streets were gone. It’s all television now. I couldn’t even get my bearings. And clubs!” He shrugs. “They’re almost all gone, even in New York. The Copa’s finished. Ben Marden’s Riviera in Jersey—they’ve made a road through it.”

He stands up to leave. “Ah, what are you gonna do? It’s a whole new business.”

At seven p.m. the next evening, in what is evidently a sharp break with custom, the Ritzes find themselves in a fashionable downtown restaurant in the Union Plaza Hotel. Harry, duded up in a blue corduroy suit, has sat quietly talking about old times with his host, a local show-business columnist and television-talk-show host named Forrest Duke, who has lately assumed the role of official greeter at the restaurant.

“You know how we got started in this town?” Harry asks now. “Moe Dalitz helped us. He’s the one who advised Bugsy Siegel to take us.”

“Let me tell you something,” says Duke, a stoop-shouldered, owlish man who calls himself the Duke of Las Vegas, “people have said a lot of bad things about Moe, but he was one of our top citizens.”

“He helped build the synagogue,” interjects Naomi.

“That’s right,” says Harry. “I wish those guys would come back. The town hasn’t been the same since they left. These days things are so expensive, you gotta pay every time you wanna take a pee.”

There is a long pause. “Harry,” says Naomi, “tell about the time you peed in Adolphe Menjou’s hat.”

“I didn’t do it on purpose,” replies Harry. “I thought it was Merman’s.” He grins and nuzzles against Naomi. “But,” he says, turning back to Duke, “I do have this one bit about a man peeing at various stages in his life. I can’t do it here—I gotta spit water out of my mouth to do it right—but I’ll show it to you sometime. You know, when he’s eight years old, the water spills all over the place; when he’s twenty-seven, it’s in a fairly straight line, well aimed; by the time he gets to be an old man, it’s gushing out in all directions. It’s a funny bit.”

During Harry’s story the maître d’, a distinguished-looking gentleman with an Eastern European accent, has arrived and is hovering over the table. “Pardon me,” he says to Duke, “I want to tell you. I just got a registered letter—Elisabeth, my daughter, just graduated as a neurosurgeon in Germany.”

“That’s wonderful,” says Duke.

“Beautiful,” agrees Harry, to whom the maître d’ immediately hands a photo of his daughter. “Beautiful,” says Harry, studying it, “a beautiful girl.” He hands back the photo. “We never played Europe in our lives. They loved our films there—in Paris, in Romania—but we never had time to go. It’s a shame.”

“Hey Harry!”

He swings around to find comedian Milt Kamen, the star of the play being presented in the Union Plaza showroom, standing with outstretched arms. “My favorite,” adds Kamen. They embrace.

“You look great,” says Kamen, a sweet guy with a Cheshire-cat grin and a perpetual squint. He pulls up a chair to the table. “You know, Pauline Kael was in town, interviewing everyone who ever knew you. I hear she wants to write a big story about you.”

Harry nods. “Yeah, she loves me.”

“Harry’s writing his autobiography,” says Naomi.

“That’s right,” says Harry proudly. “I’m calling it From Rags to Ritzes. It’ll have a lot of great stuff about our career in it. Not like Berle’s book, where all he did was talk about how many girls he screwed.”

“It’s true,” agrees Kamen. “After all this man has done, he dedicated a book to his penis.”

“We used to have a long-schlongs club,” says Harry. “Berle, John Ireland, Gary Morton, me and Forrest Tucker. Oh, boy, Tucker was tough to beat.”

Kamen grins.

“Hey,” continues Harry, turning to Naomi and Duke, “did you hear the one about the ninety-four-year-old man who goes to the whorehouse? He says, ‘I want a girl.’ The madam looks at him and asks, ‘How old are you? You look like you’ve had it.’ The old man reaches into his pocket. ‘Really?’ he says. ‘How much do I owe you?’”

Harry throws back his head and laughs loudly, joined by the others at the table. “Better not tell that to Berle,” says Kamen. “I once told him a very sad story about my life, and the next day he was telling it at a party as if it had happened to him. The man stole my life.” He pauses. “But why am I telling you?” he adds. “He’s probably taken more from you than anyone else has. Like all the gay bits, all the stuff in dresses.”

“We were doing faygeleh stuff forty years ago,” Harry acknowledges. “We killed ’em with that at the Palace.” He shrugs. “Hey, you wanna see a fag with an inferiority complex?” He purses his lips, covers his face with a dainty hand, flits his eyes nervously about.

Kamen nods vigorously. “That’s what I mean,” he proclaims to no one in particular. “Without Harry there would be no Berle, no Danny Kaye, no Sid Caesar, no Jerry Lewis! So many concepts and attitudes originated with Harry. Who ever heard of parodying opera before Harry? Myself, I’m a highly distilled Harry Ritz.”

“All true,” agrees Duke.

“Harry,” says Kamen, turning to him, “you’re the best. I’d give anything to watch you work tonight.”

Harry glances at Naomi. “Yeah,” he says, “but she don’t like me to do clubs here. It’s no use knocking my brains out.”

She nods. “He works so hard in the act his shirt is soaking wet.”

“Anyway,” adds Harry softly, “the business isn’t fun like it used to be.”

Kamen understands. “It’s a simple statement, but it’s true. They’re like computers now. They’re heartless bastards.”

A silence falls over the table. “You wanna hear something really sinful?” Everyone turns toward Naomi. “At Grauman’s Chinese Theater they’re tearing out the stars from the Twenties and putting in today’s little TV stars.”

“No,” exclaims Kamen, genuinely shocked.

She nods. “Thank God they haven’t gotten around to the Thirties yet.”

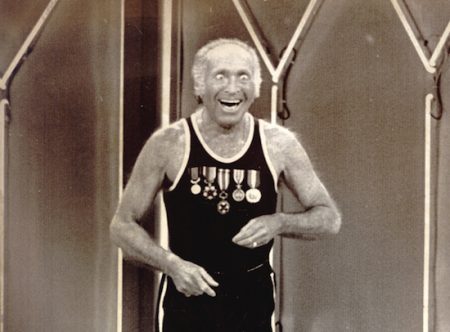

Harry has a ball at Kamen’s show, a comedy called Norman, Is That You?, about a father discovering his son is homosexual. But what he enjoys even more is a little speech Kamen delivers after the curtain falls: “Ladies and gentlemen, we have with us tonight one of the greatest comedians who ever lived—and this is from a time when ‘great’ meant something—Harry Ritz.”

Harry stands in response to the applause and gives a jaunty little wave. “Look at that,” he remarks, beaming. “This always happens when we go out.”

But Harry’s night is not over. Striding through the Union Plaza lounge on his way out of the building, he is accosted by the cocktail pianist, a peppy middle-aged guy with a goatee, named Page Cavanaugh. “Harry Ritz,” exults Cavanaugh, “my favorite comedian in the world!” He gives him a hearty slap on the back.

“Thank you,” says Harry, delighted. “It’s a pleasure seeing you again.”

Cavanaugh turns to Naomi. “This man gave me the greatest laugh I ever had in my life. At a party for Gloria De Haven. He did this imitation of Pegleg Bates and I cried.” He starts chuckling at the very thought of it.

“Oh, yeah,” says Harry. “Pegleg Bates was that colored dancer with one wooden leg.” Without missing a beat, he starts tap-dancing joyously—with an enormous, toothy grin on his face—but with one leg stiff as a board. It is a tap-hobble, actually, and it is incredible. Page Cavanaugh cannot help himself; he doubles over and almost sinks to the floor. “More, more,” is all he can manage.

“Ever see John Barrymore do the Charleston?” asks Harry. He launches into a haughtily disdainful rendition of that chaotic dance, taking enormous care to keep his profile—nose tilted slightly upward—in full view at all times.

“Don’t stop,” begs Cavanaugh, his eyes full of tears.

“Remember Deadlegs,” shouts Harry, “the Lon Chaney character with two bum legs? Ever see him do the Charleston?” He sets his face in a menacing scowl and swings into a tortured Charleston, picking up one lifeless leg and then the other with his hands.

Cavanaugh, who by this time is clutching a chair to keep from collapsing, can no longer speak, and Harry decides to make his exit. He takes Naomi by the arm and starts ushering her from the room. Then he stops. “Charles Laughton didn’t do the Charleston,” he calls back, “but he liked to watch it.” He puffs out his belly and lets his face go slack. “Mr. Christian,” he demands, in perfect imitation of Laughton in Mutiny on the Bounty, “come on deck and do the Charleston for me.” He strides out the door as Cavanaugh staggers back toward his piano.

Outside, in the neon glare of the Union Plaza entrance, Harry is positively glowing. He cannot stop himself now and he doesn’t even try. He spots a pair of tourists a few yards away waiting for an attendant to deliver their car. The tourists are leaning against each other, obviously exhausted from a long night at the gaming tables.

Harry dashes up to within a yard of where they stand and goes into his version of a man with a double hernia doing a jig. He jumps around frantically, clutching his crotch, all the while maintaining a kind of rhythm.

The couple stare at him in bewilderment. Harry laughs and runs over to Naomi. “Look at that,” he says, “they think I’m crazy out of my mind. Look at them watching me.” He shakes his head. “Crazy Harry Ritz, that’s what they’ve been calling me for forty years. No one can say I’m not as crazy as ever.”

[All Photos c/o Melinda Ritz]