If fate ever condemns you to suffer through a really bad movie, pray that some quirk of same puts you in a seat next to Pauline Kael. She cannot make what is happening up there on the screen go away, but she can jolt you into a kind of super-awareness of why what you’re looking at doesn’t succeed. That is the experience she recreates so tellingly week after week in her reviews for The New Yorker. It is a combination of the visceral and the cerebral, and it succeeds in making you care, in making you realize, for example, why you want to machine-gun the screen after seeing something unusually ghastly. “Soldiers have done that during wartime,” Miss Kael recalls matter-of-factly. “They’ve shot up the screen. They did it during World War II, at a movie called Four Jacks and a Jill. And they did it at other pictures, too. They shot up the condescending, patronizing, patriotic pictures.”

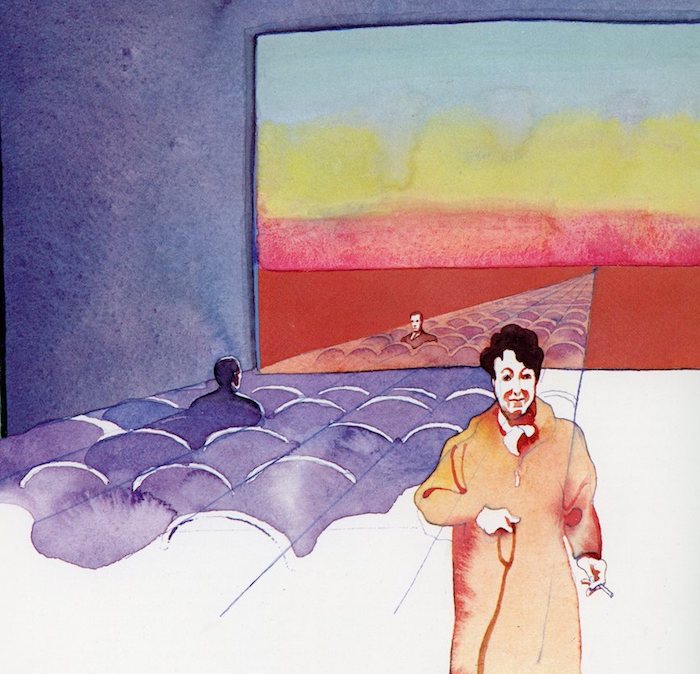

Miss Kael imparts her special presence no matter where she sees a movie, in a crowded commercial theater or in a by-invitation-only screening room. Take one particular screening: It is maybe half-an-hour into the movie, people around you are starting to mumble things like, “Oh, Jesus,” in that disgusted tone of voice that says they are really tired of being used, again, and next to you Pauline Kael, a small lady who has to move from one seat to another when anyone at all big-shouldered sits in front of her, sinks even lower in her seat and, eyes still glued faithfully to the screen as for the fourth time now a hypodermic needle slides lubriciously into the veins of a compliant actor willing to portray the agonies of addiction, says with more weariness than annoyance, “Oh, my God….”

A heavy, at times emotional sigher, Miss Kael is not the critic who talks most relentlessly during movies. “A lot of them talk,” says Charlie Powell, former National Publicity Manager for Columbia Pictures. “The classic is John Simon. He mumbles to himself in German through the whole film.” Miss Kael is not quite like that. But when she has really had it with a picture she lets you know. Watching a particular drawn-out scene in which nothing at all is happening, she sits up and whispers, really only to herself. “They’re dishrags up there.” And then at a certain moment, weary of talking either to herself or the movie, she whips out a small pad and a pencil and begins taking notes furiously: short notes scribbled hastily, eyes never leaving the screen, hand working across the tiny piece of paper, finger flipping to the next page, hand writing on and on, eyes on that giant screen, head dropping for one moment only to see if, by chance, she has written right off the edge of the pad and onto the purse and raincoat lying on her lap.

This lack of reserve prompted Cinerama Releasing Corporation not too long ago to initiate a policy of individual screenings for each critic because her remarks were affecting her fellow critics. As one of New York’s top independent film publicists, who prefers to remain anonymous, says, “They [her fellow critics] like Pauline a lot and they respect her a great deal, and when Pauline says, ‘Oh, my God, what a load of crap!’ and they know that that’s going to be in an anthology in six months”—he has to laugh at this point—“I think it affects them.”

Out on the street after the screening, Miss Kael asks, “Can you imagine somebody taking someone to a movie like that!” She doesn’t wait for an answer but muses about what can possibly be gained from seeing the movie she has just seen. Yes, drugs are death, and addicts lifeless, she says, but the movie has been so relentlessly, so monotonously depressed and undeveloped. “They are killing the audience!” And Pauline Kael desperately wants people to go to the movies.

There is a kind of ferocious tenacity about the way she acts on this conviction, a fanaticism about what a film is capable of being, that makes movie executives cringe in the privacy of their corporate sanctuaries and publicists worry about who she’s going to rend asunder next. They seem to think of her as a nagging terrier who, jaws locked and hold secure, hangs on until the lumbering Hollywood-made behemoth is brought, whimpering, to its knees. But rather than admit this they speak of her with an odd blend of pragmatism and circumspection because, as former Newsweek film critic Joe Morgenstern puts it, “They’ll need her on their next movie, and they know it.” They say things like, “When she likes one of your films you’re very happy about it, when she doesn’t you’re very unhappy about it. At times she’s infuriating, at times she’s quite lovable, depending upon what she’s saying about your picture.”

Miss Kael is aware of the power of her position. “With a new movie,” she says, “if you point out too many of the things that are the matter with it, people will use that as an excuse not to go. If you get anything out of a movie, I mean if there’s anything there to be gotten, help people to get it. Never give them the excuse to stay home if there’s anything there on the screen. There are so few movies that really offer you anything that’s fresh, that’s different, that’s exciting. And there are so few movies where the life and death of that director makes a difference in the history of the art.”

A few weeks later the conviction is put to the test. The father of her twenty-two-year-old daughter, Gina, is in New York—Miss Kael is divorced, three times according to some published sources, four according to others who refuse to be identified—and invites Miss Kael to some kind of a film-people dinner in Chinatown. At the last minute she calls and begs off because she feels it is much more important to go back and see Robert Altman’s newest film, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which she has already seen once, and has written about at great length and with thoughtful enthusiasm. She wants to see the movie again to be sure her sensibilities haven’t failed her, that some unrecognized state of mind hasn’t influenced her unduly. She is, she admits readily, worried about the movie’s future and feels her review is important to its survival. She is seeing it again so she can say, as unequivocally as possible that, yes, she is absolutely sure it is damn close to being a masterpiece. Going into the screening room she says, “I’ve rarely wanted a movie to succeed as much as this one.” So Gina’s father is left to go to the dinner alone and Pauline Kael is in the screening room waiting to find out if she was right.

If seeing a bad movie with her is a small adventure of survival, seeing a good one is no less illuminating, even though she says not a single word and jots down only four words of notes during the entire showing. Her enthusiasm for what the director has put onto the screen produces in her a radiating silence and incredible attention. There is also a certain anxiety, since she feels she’s still alone in her affections. When the picture ends she has confirmed all of her excitement, and now, standing up to leave, senses the indecisive optimism hanging in the air. People are saying things like “Interesting,” and “I really think it’s going to do well,” with about as much conviction as a skier with a double spiral fracture who keeps telling everybody he’s going to be back on the old boards in no time. She excuses herself to walk over and say a few words to Robert Altman, telling him once again how much she loves the film. They talk quietly for a moment or two and he seems to appreciate her words. He must know she’s not lying because she didn’t hesitate to tell the world how little she thought of his previous film, Brewster McCloud. As Miss Kael leaves the screening room the talk is definitely not about big box-office; nobody is willing to declare, for the record, that this one’s going to be a hit. But by returning to see it a second time, Pauline Kael has honored both Bob Altman and his achievement.

Miss Kael’s faith in movies does not mean she is beyond throwing in the towel when a particular picture turns her off completely. “I walk out all the time,” she admits candidly. “I walked out on Quo Vadis, for example. But l’d never walk out on a movie and then review it without indicating that I’d walked out; I mean, I wouldn’t pretend, because suppose the last ten minutes was brilliant and I didn’t see it? Which, you know, is conceivable, although rare. Generally speaking, if it’s so bad I walk out, I don’t mention it. That generally means it’s going to flop anyway. There’s no reason to kick a guy when he’s down.”

Miss Kael goes to the movies constantly, even during those six months each year when Penelope Gilliatt replaces her as film critic for The New Yorker. During her own six months she is under constant pressure. “Say my deadline is Tuesday, which it is,” she explains, her voice barely suggesting the urgency which pursues her from screening to screening. “If I go to the movies all week I may not see the movie I want to cover till Monday night. So then I stay up Monday night and get the review in on Tuesday. I may see it Sunday afternoon; I may see it Saturday. I see a lot of movies for every one or two I write up; or the two or three. Very often I make notes during a movie, but I don’t remember to look at them when I write the review. You want to be sure you won’t forget something, but then who has time to look at his own notes? You write fast if you’re a critic.”

“William Shawn is a great editor. He really is what a writer looks for; it’s what you never think you’II find: an editor who gives you space, who doesn’t let anybody pressure you and who pays you.”

She writes all of her reviews in longhand, sitting on a straight-backed chair on the seat of which is a doubled-over bed pillow. Her desk is a large drafting table with a gawky-looking elbow-lamp attached to one corner. Scattered over the table’s broad surface are various small rocks, sea shells, and an antique double-welled inkstand with both wells filled to overflowing with paper clips; there are scraps of paper with scribbled notes, a diary, jars of pencils, and a large electric pencil sharpener. A copy of the Random House Dictionary sits on a four-sided book hutch next to the drafting table. When the phone rings, she answers it almost immediately, even when working. She laughs or commiserates readily with whoever is calling about whatever it is that is going to happen or was meant to happen, keeping the conversation headed steadily toward termination. She will, if disappointed by some bit of news, utter a very ladylike and precisely enunciated “Oh, shit,” managing, unlike that famous Radcliffe girl who died at the tender age of twenty-five, to lend the expression genuine personal charm.

It often takes her most of the night to finish a review. Behind her, through the double doors leading into her bedroom, Bushy, the surviving male of a much-loved pair of wizened-face basenjis, burrows among the blankets on her bed and keeps her faithfully silent company. When she has finally finished, she leaves the review for Gina to type up in the morning. By the time Miss Kael awakens, the typescript is finished and she checks it over, adding phrases here or there if she decides she hasn’t made a point with sufficient emphasis or grace. This meticulous attention to both detail and style is the reason so many people read her not only to find out what she thinks of a movie, but because she’s a genuine writer. As one former senior studio executive didn’t hesitate to say: “I think it’s generally accepted that Pauline is one of the finest writers and critics working today.” Former Columbia Pictures executive Charlie Powell says, “I think Pauline is one hell of a writer; I think she’s as good a film writer as there is.”

When she has finished her corrections, Gina retypes the review. Then, toward six in the evening, a messenger from The New Yorker appears to pick it up and take it directly to the home of William Shawn, the magazine’s editor-in-chief. “Shawn has to go through it and take out any dirty words,” Miss Kael says merrily, as if enchanted to acknowledge her respected editor’s fame as a somewhat conservative man. Two hours after he has received her review he calls, usually to say no more than that he has received it and everything is fine. He may go so far as to say, “It’s a good piece,” which for Pauline Kael means, as she admits, “a good night’s sleep.” She explains, “Shawn is a great editor. He really is what a writer looks for; it’s what you never think you’II find: an editor who gives you space, who doesn’t let anybody pressure you and who pays you. You know: space, freedom, and pay … God.”

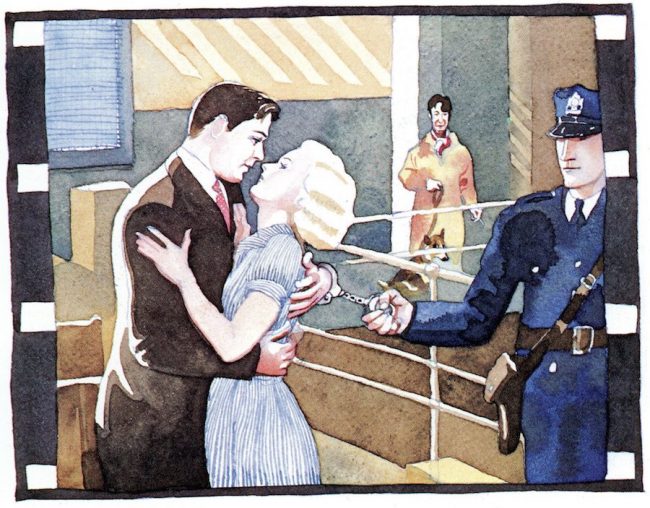

That softly uttered God is not to be taken lightly. Pauline Kael has been hassled one way or another ever since the day people in the movie industry realized this disarming-looking, small-featured and bespectacled woman who had spent twenty-five years fighting to write about movies the way she wanted to write about them, was here to stay. When Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge is being screened in New York for critics and that ephemeral crowd known as the taste-makers, she finds herself being kept out of all the screenings. Though this occurs during her six months off the magazine, she has agreed to do the week’s review because it is fairly common knowledge around the film industry that Nichols and Miss Kael’s fellow New Yorker film critic Penelope Gilliatt had been close friends at one time, and The New Yorker does not want to be suspected of printing either a very good or a very bad review of Carnal Knowledge for reasons that have nothing to do with the film’s excellence. So Pauline Kael calls the distributor every day for almost a week, asking when she can come and see the picture. There is always a reason why she can’t, and she’s wearily accustomed to all the ploys. “They no longer say ‘We won’t let you in,’” she says. “Now, they often don’t ask me until the last minute. Or they somehow manage to overlook me so that I won’t make my deadline. They just maneuver so somehow they forget to ask me, and if l phone, and say ‘I really need to see it,’ they say ‘Oh, we’re sorry. We’re not holding any more screenings. It was an oversight we didn’t ask you.’ All that kind of stuff.” She shakes her head in disgust, then, looking as if she’s about to burst out laughing: “My daughter’s been invited by friends to see movies that the studio men told me they hadn’t screened yet! The fact is, they know I can see it on opening day and still get the review into The New Yorker, but what they’re afraid of is that newspaper critics in other parts of the country may be paying a little attention to me. If possible, they like me to be late, that’s all.”

Eventually, because she must see Carnal Knowledge, she calls John Springer, press representative for Mike Nichols. Springer is genuinely upset at what is happening and assures her she will be on the following evening’s list. When she arrives, her name is not on the list and the functionary at the door refuses her entry. She patiently explains that John Springer has arranged for her name to be on the list, constantly interrupting her quiet argument to turn and greet people she knows as they file past her into the screening room. When Springer himself appears, she appeals to him. Springer takes the guard aside and they converse for several moments in hushed voices. “They cater to the press they know they can count on,” Miss Kael observes with intentionally serene indifference. “They prefer people they can trust; they know there are certain people they can influence, you know, indirectly, nicely. Nothing overt.” Springer comes back, apologizes for the misunderstanding, and motions her into the now packed screening room. She watches Carnal Knowledge sitting on a folding chair in one of the aisles.

A few days later, looking back on the whole silly business, she says, “They’re such poor judges, they never know what I’ll like or what I won’t like.” A former studio executive agrees, “You can’t really find why she didn’t like one picture when she did like one like it a short time ago.” Then, perhaps because this sounds as if he thinks Miss Kael irrational, he feels compelled to add: “I guess everybody’s human.”

Particularly human are those film industry executives who continually find ways of hedging their reservations about the actual extent of her power. Says a vice president of one of the major studios, “I don’t know that she makes or breaks movies.” Says Charlie Powell, now assistant to Hollywood producer Mike Frankovich: “Most movie people honestly feel that with the exception of two or three critics around the world, criticism doesn’t hurt or help most films, that there’s only a certain type of film that a review such as Kael’s will affect. That goes for all average Hollywood films, with the exception of a four-star review in The Daily News—Wanda Hale’s review is a goddamn sight more important than all the other reviews put together. We’re not for a specialized audience; the mass audience never even heard of Pauline Kael. l also contend that a lot of people who read her aren’t moviegoers anyway, they’re just readers, clever readers who see two pictures a year. She doesn’t affect us one way or the other. I don’t say it arrogantly, I say it realistically.”

A New York publicist disagrees: “You read Pauline everywhere, and you see Pauline everywhere, and she goes on television shows, and she goes on Barry Gray (a popular radio talk show in New York City) and the other critics regard her with a good deal of awe, and if the executives had any brains—and they don’t—they would recognize that if you go around the country and talk to most of the young critics, you’ll find they became interested in film because of Pauline Kael. You talk to Gary Arnold, in Washington, or Roger Ebert, in Chicago; I mean they are Pauline Kael’s children, whether she knows it or not. She’s had an enormous influence on the business when you have someone who’s as iconoclastic as Arnold reviewing in a city like Washington where the other critics write like idiots. Her influence on that level has become enormous. And she also sort of made film criticism a legitimate concern for literate young men. Not only because she’s a good writer, but also because she wrote about film as if she liked it. People sort of assume the lasting review will be Pauline’s. That’s the enduring review, that’s the one that’s going to be collected.” The man pauses, and then, experienced enough to be a realist, adds, “I like Pauline a lot though I don’t like to see her walk into my screenings. Under any circumstances.”

Certainly the most famous Pauline Kael cause-célèbre involved her review of The Sound of Music, which appeared in McCall’s in 1966, during the few months she was its reviewer. “The audience for a movie of this kind,” she had written, “becomes the lowest common denominator of feeling: a sponge.” When, soon thereafter, she was fired from the magazine, a lot of people were convinced it was because that particular review had produced enormous pressure from Twentieth Century Fox. A film industry executive close to the episode at that time denies it: “I can say that it’s absolutely untrue, that no one involved with the studio raised a finger. I ran into her at that time at a meeting that was hosted by the Motion Picture Association for Jack Valenti, and she had just been fired a week or so before, and she and I suddenly found ourselves in the center of a ring of people expecting a big brawl. l think she was very bitter and was under the impression—or chose to believe—that we had gotten her fired. I told her then that this was not true, that we hadn’t done it. The picture had mixed reviews—I mean it wasn’t all pans—but I would say the serious critics tended to pan it, and by that time we knew we had a hit of phenomenal proportions; another highbrow blast would not affect business.”

“I suppose it made a good story that a big, sloppy mass magazine like McCall’s wasn’t going to let anybody criticize a big treacly movie like The Sound of Music. It wasn’t about that at all.”

Miss Kael herself has never insisted she was fired just because of her Sound of Music review. “It was because of a lot of movies,” she says. “There was a definite change of policy on the magazine and I was part of the policy they dropped.”

Bob Stein, who was editor of McCall’s at that time and who, with the change of policy, was moved upstairs to the position of senior vice president, agrees only too happily that it was much more than The Sound of Music that got her fired. “It was really more complicated than that,” he says. “We had signed her as a reviewer on a six months’ basis. It was admittedly an experiment, because she wasn’t by any stretch of the imagination a natural choice for a mass magazine reviewer. But we were trying to do better things in a lot of areas in the magazine and we thought we would try her. What happened over a period of some months—and I should say that I was a great admirer of hers before I hired her and l’m a great admirer of hers still; I read her reviews religiously—but what created a problem for us, was that she was doing short reviews of a lot of movies, which is not her best running time.”

Miss Kael remembers wanting to prove that the generalizations made about the fifteen million women who bought and read McCall’s were wrong, that they had views of their own and were open to fresh opinions. She failed.

“When you’re editing a large magazine,” Stein explains, “it’s very hard to isolate your responses on any single thing because you’re dealing with so damn many at the same time, and God knows I may have transferred my problems about other things to Pauline, but I did get the progressive feeling that there was a nasty edge to some of the things she was doing, and what sticks in my mind is when it just got personal. For example, she would criticize Lana Turner for getting old, and she would criticize producers for what their previous occupations were—things like that—which seemed to me not in line with the kind of reviewing of hers that I admired. I don’t know what particularly brought it on. My own guess is that reviewing for a mass magazine, she seemed to have some need to make it clear how independent she was. She would say: ‘Doesn’t Paul Newman have anything better to do than make a picture like Harper?’ Okay, she’s the reviewer and I’m not. She can say Harper is a bad picture from here to doomsday and deal with the picture, but I did find that she would continue to sort of gratuitously attack people ad hominem for their motives, their backgrounds—God knows, poor Lana Turner for her age—and I really objected to that. That’s a luxury I didn’t allow anybody else who was writing for the magazine. It’s not too characteristic of her, and may very well have been a symptom of her unease, that she was in a cramped position somehow writing for the magazine. I tried, even at the time, to make it clear that I wasn’t mad at her, that it wasn’t The Sound of Music.” Stein stops abruptly. “First of all,” he says quickly, “the movie people don’t have any hold on mass magazines. They never did. They used to advertise. They haven’t advertised for years. So even if you tried to picture the situation at its most venal, what force could their complaints have had? Probably, perversely, we would have gotten tougher about backing her up if they had put some pressure on us. No, it’s just that I got uncomfortable with what was doing and I didn’t think it was right, and I’m sorry, and even looking back at it from this distance, it’s one of those things I don’t know about. I may have overreacted.”

“As a matter of fact,” Stein goes on, “that piece on The Sound of Music was one of the ones I liked best. I was quite pleased with it because that seemed to me to be a very proper thing to be doing in a mass magazine, to deflate something that was that popular, that many of the readers either had seen or might see. So l had really no objections to that and I don’t know how the story ever got started that it was about The Sound of Music, except that I suppose it made a good story that a big, sloppy mass magazine like McCall’s wasn’t going to let anybody criticize a big treacly movie like The Sound of Music. It wasn’t about that at all.”

An executive who was involved with the episode from the studio’s side says, “It’s possible she was fired because the editors concluded that she was out of touch with the readership that they were catering to. And their view of criticism was of something to be a guide—what to see, what not to see—rather than what to think about.”

In any case, the major studios were delighted to see her go. “If I hadn’t gotten the job at The New Yorker,” Miss Kael says bluntly, “I’m not sure that I’d still be a movie critic. There was a period there when I wasn’t allowed into screenings, when four of the majors were keeping me out, and they effectively drove me out of the monthlies.” (Most people seem to have forgotten that she used to contribute to quarterlies such as Sight & Sound and Film Quarterly, and monthly magazines such as Harper’s, The Atlantic, Holiday, Mademoiselle, and Vogue.) “You can’t write for a monthly magazine,” she explains, “unless you see the movie when they first screen it. You can write for a weekly, but they kept me out of the big important monthlies.”

The animosity expressed toward her seems to have been grounded in more than her outspoken criticism. As the New York publicist explains, “Pauline doesn’t play any of the games. She doesn’t dress New York, she isn’t polite and social—none of those things. I remember when she first came to New York, which would’ve been six or seven years ago. She showed up at something wearing a dress with a hole in it, under her arm, and it was really The Scandal. I remember her showing up that way, and everybody being just totally horrified, just really horrified that she would do this. You look at the other female critics and by and large they’re a fairly chic, social group of ladies who play the success game very hard, and on one level or another are susceptible to all sorts of inducements. Sometimes just attention does it: sending a car.”

“I don’t fraternize in general,” Pauline Kael says, less as a statement of principle than of fact. “I don’t do interviews, and I try to avoid most actors and actresses. They don’t understand what criticism is about: they think it’s all just personal bitchery.”

“Pauline,” says the publicist, “plays none of those games at all. There’s just no way anybody can get to Pauline, they’ve got nothing to offer her; because she isn’t interested in the movie business, she’s interested in the movies.”

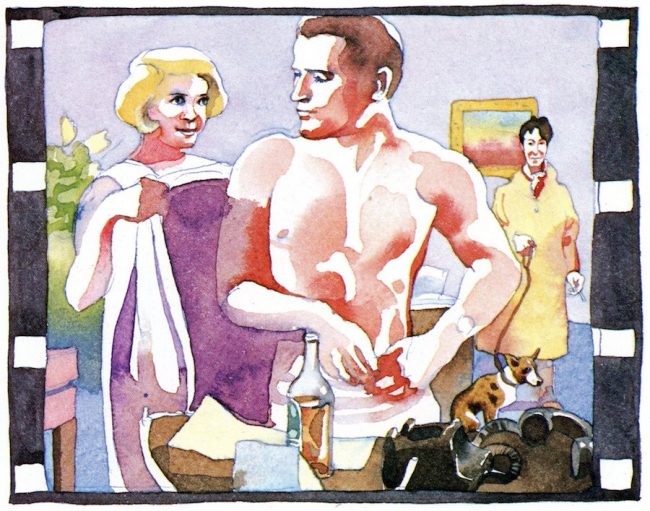

“The most common way that movie critics are bought,” she says late one evening, “and I mean bought in the specific sense, is that the producers hire them to write a movie script. The movie script is never made. It’s put on the shelf. But they give them eight thousand dollars, or ten thousand dollars, or fifteen thousand dollars for it, and, that man is able to buy a house in the country, or a farm, or something. He’s got a little bit of property, and he’s perpetually beholden to those producers, and those companies, because they’ve given him that little bit of dough. Once you work for them, you are theirs. It’s one of the reasons for not writing movie scripts. Chances are the movie’ll never get made, or will be rewritten. I mean, the chances of their using your script are rather slim. It’s one thing if as a critic you get to know a director and you know what he wants and you write a script for him. But if you deal with the producer, or a company, to write a script for them, they’re simply buying you. Chances are it’s twenty-five thousand dollars in the bank and that’s the end of the transaction. But you are their man. And l will not be their woman.”

“She’s had offers,” says Bob Mills, Miss Kael’s literary agent. “I don’t know about writing, so much, but as an assistant director, a ‘technical advisor.’ There have been a number of inquiries of that general nature.”

Those who go for it don’t surprise or upset her. “Most of the critics who do that are not good critics,” she says simply. “The good critics who are writers in any sense—Gavin Lambert, for example—some of their work gets made. I mean Agee’s work, some of it at least got made and the rest got published. Penelope Gilliatt, her film (Sunday Bloody Sunday) is made. But the critics who get ‘bought’ by the studios are not surprised when the films are not made. There are many, many, many who have done this. And I think they deceive themselves.”

It is, as even Faulkner and Fitzgerald have been ready to admit, the money. “I am staggered,” she says, “by the fact that a mediocre writer, who gets one movie on the screen, can then command a price of a hundred, or a hundred and fifty thousand, to adapt a novel. He doesn’t even have to write, he just has to do reconstruction. You know how hard other people work for money. I mean, no one else sees that kind of money. It’s only in show business—or now in music—that people make amounts like that. It’s totally irrational. But these second-rate, fourth-rate writers, who’ve never written anything or published anything under their own name—maybe a couple of television adaptations or television originals—six months of their work, constructing a screenplay out of a novel, are apparently worth a hundred thousand dollars to somebody. But that is incredible in terms of the salaries in this country, and how other writers live. I mean, most good writers never come near money like that!” Then she adds, with a tiny note of unexpected regret. “And it took me so long even to make a living as a writer at all.”

Her resentment, what there is of it, is directed not so much at the years she struggled to achieve her present eminence, but at the energy it all consumed. “I’ve made about twelve starts,” she says. “The awful thing is that they consume your best years. They took away the energy I need now.”

In order to survive over the years she was a cook and a seamstress—“God, two years as a seamstress! Do you know what that does to you? You know, not only your eyes?”—and she wrote advertising copy, first for Houghton Mifflin and then for American Book. She sold baby photographs and insurance over the phone from home for seventy-five cents an hour, and she gave music lessons, and tutored people in what she remembers as “weird fields I don’t know anything about, like anthropology.” She sold books—“what writer hasn’t?”—and ghosted books, preferring to forget their titles because, this said with a quick laugh, “there’s ethics in crime.”

Pauline Kael was the youngest member of a large family and lived on a farm thirty miles north of San Francisco. “I remember my father,” she wrote toward the end of a long review of Hud, a review directed in part at those critics who found the character of Hud to be that of a dangerous social predator because of his indulgences: “I remember my father taking me along when he visited our local widow: I played in the new barn which was being constructed by workmen who seemed to take their orders from my father. At six or seven, l was very proud of my father for being a protector of widows….My father, who was adulterous, and a Republican who, like Hud, was opposed to any government interference, was in no sense and in no one’s eyes a social predator. He was generous and kind, and democratic in the western way that Easterners still don’t understand….” Miss Kael has never written so boldly of her mother because she feels to have been much closer to her mother than she was to her father. But it was an inner closeness rather than the remove from which she knew her father. He was more considerable as a subject for her opinions; her mother was … her mother.

When she was eight, the family moved into San Francisco. She read voraciously all through high school and college. At college, she majored in philosophy of history, but most of her friends were English majors and she remembers arguing with them endlessly about Ezra Pound and James Joyce. She was first drawn to film criticism when she worked with such underground filmmakers as James Broughton. Her creatively formative years were centered at Berkeley, where, in the late 1950’s, she successfully managed twin art-movie houses: the “first twin art-movie houses in the country,” she says with pride. She was married, not very happily, and living in a home where the prized possession was a gigantic 35mm projector sitting in the middle of the living room. It was, as one person remembers it, a monster of a machine, with a throw that “went right through the living room, the dining room, into the kitchen.”

“Why when someone works for a long time to become a good critic is it necessary to say, ‘Why don’t you become a screenwriter? Why don’t you become a director?’ Do you know how hard it is to be a good critic?”

Less palmy days are remembered in unusual terms. “I never saw The Greatest Story Ever Told,” she says unexpectedly, as if to tell herself it really happened once upon a time, “simply because it was rather expensive to see. At this point it seems rather beside the point. But I was embarrassed one day when I had lunch with the director, George Stevens, and he wanted to know what I thought of it.”

She clearly remembers her success as an advertising copy writer because she gave it all up so suddenly.

“The day they were putting up the partition and putting my name on the door I went in and quit in tears because I suddenly saw myself behind that partition for years. And I didn’t want that, I wanted to write.” The moment seems oppressively vivid, and she shakes it off. “The main thing is fighting off the successes that trap you. That’s the really weird part of it.”

Late one afternoon she finds herself trying to explain why she hasn’t considered imitating her French counterparts, critics like Truffaut and Louis Malle, and become a director. “I wanted to do those things thirty years ago,” she says patiently. “Now, it would be very stupid—” She catches herself in mid-sentence, and then, angry now at having to answer this unpleasantly familiar question. “Why aren’t people satisfied with the fact that I try very hard to be a good critic. Why when someone works for a long time to become a good critic is it necessary to say, ‘Why don’t you become a screenwriter? Why don’t you become a director?’ Do you know how hard it is to be a good critic? The whole thing that sustains me in writing is to tackle new ideas, new subject matter, new areas: but the whole thing of changing myself and becoming something else….”

She slows, and explains further. “As you grow older, you have to accept the fact that the steps you’ve taken have turned you into a certain kind of person. When I ran theaters, I had the kind of business sense to deal with the film companies. I no longer have the kind of disposition I’d need to deal with the unions, and all of the tough men, and the crews I’d have to deal with if I became a director. If I went into directing, or into something actively involved in making movies, I’d have to go back into business.” She understands what it takes to be a director in this country. “He has to be, a good part of him, a businessman. Or work, as a team, with a producer, who keeps the business pressures off him. It’s what’s killed most American directors. They don’t have anyone to take off the business pressures; they spend all their time setting up the deals, rather than making the movie. If Sam Peckinpah had someone to handle the business he could be a truly great director.”

She laughs suddenly, reminded of something. “By the way. I have this thing which I point out to Gina: when directors come to see me, and very often they do—often I’ve never met them before—they always come into the apartment and sit down in a certain chair.” She points to it, a simple straight-backed chair, one of four around a table. Sitting in that chair you get a breathtaking view of Central Park, including the entire breadth of the reservoir which, toward dusk on almost any day, takes on a mellow, almost somber, tone, with to or three seagulls floating placidly on its surface. Beyond the reservoir, resting among the trees like some concrete conical hat, is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum. And around it all is the anomalous serenity of the park as seen from this distance. “The first time Peckinpah ever visited here he came in the room and sat down in that chair. And it’s not because I was sitting opposite. Often directors sit down before I do.” She laughs again, pleased by how she noticed this absolutely lovely thing, pleased to know how right a touch it is. “I think,” she says, “it’s so they can command the vista. Peckinpah sat in that chair, Kershner sat in that chair, Wyler sat in that chair, Mazursky sat in that chair, Altman sat in that chair. They have never sat in another chair in the house. Recently, a director—and it made me very nervous—came in, and sat in that chair—” she points to another chair, more of an easy chair with arms, which faces in a different direction, “—and I thought to myself, ‘He’s going to have a flop.’ It really made me nervous.”

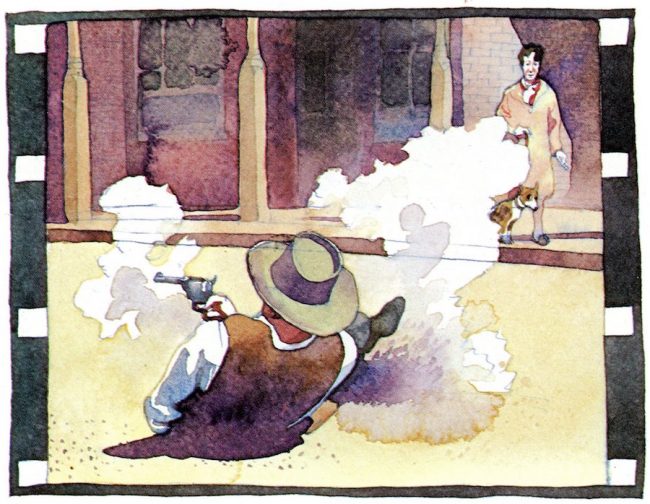

She talks as directly as she writes and while being all sweetness and light about Sam Peckinpah—“I voted for him as the best director of the year that year”—suddenly, veers like a car in which the driver has floored the gas pedal for no apparent reason, and says, in answer to an innocuous comment about Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers: “You really feel you should drive a stake through the heart of the man who made it. I mean it is so vile. It is so horrible. I know all sorts of people who didn’t believe my review, went to see it, and phoned and said, ‘You didn’t make it bad enough. It’s the most horrible thing I’ve ever seen!’”

Pauline Kael has never retreated from a printed review—she stands by what is published—but she is willing to admit a factual error on those rare occasions when she makes one. She is so seldom wrong because, as Joseph Morgenstern points out, “Her knowledge of movies is encyclopedic.” But she has been wrong, and when the writer or director whom she has slighted has written to explain the mistake, she usually responds immediately and openly. Novelist James Salter, who is also a screenwriter and director, wrote her after she had criticized something in his screenplay for Downhill Racer. He explained that the passage she had singled out was not his and hadn’t been in the original screenplay. Several mornings later, at Salter recalls, his phone rang at his home in Aspen, Colorado, and a cheerful voice said, “Hi, it’s Pauline Kael.” She wanted him to know she appreciated his letter, and was sorry she had misattributed the passage in question. “It’s pretty tough,” she explained, “but you have to go by the credits on the screen.”

What does she think of her colleagues? “I think there are three or four pretty good ones,” she says. “I think at the moment Gary Arnold is good. I think Canby (Vincent Canby of the New York Times) has been perceptive. I think Andy Sarris (Andrew Sarris of The Village Voice) has some marvelous perceptions from time to time. I disagree with his theory about films as aesthetics, but he has interesting things to say.”

Sarris, unfortunately, does not return the compliment. Vincent Canby admires her, and Joseph Morgenstern, former film reviewer for Newsweek, says: “She opens up questions that nobody else opens up.” Life’s Richard Schickel recently wrote a very long piece for Harper’s in which he expressed his admiration for her enthusiastic devotion to films. But when The New Yorker published her two-part article on Citizen Kane which now serves as the introduction to the published original screenplay, Andrew Sarris answered it with a long diatribe designed both to criticize her for what she had set out to do, and to set things straight as regards Citizen Kane and what really happened. At one point, embroiled in demonstrating why she was being “maliciously misleading” in denying Orson Welles the full director’s credit—author of it all, creator of the look and style, which can be taken as a simplistic definition of the author theory—he wrote: “What I find peculiar … is the malignant anti-auteurism in the writings of Kael … as if auteurism were an established religion that had carried the day.”

When that appeared in The Village Voice, a friend called Miss Kael and read it to her over the phone. She listened, her mouth moving in a familiar half-smile, broadening and narrowing as if words and half-formed phrases were crowding her mind. When the caller had finished she sighed and said, “I wonder what’s wrong with him?” She added a small shrug, a grace note of regret, and said, “I hope everything’s all right at home.”

It is a dig, yes, inspired in part by two embarrassingly self-revelatory articles written by Sarris and his wife for Vogue. While Miss Kael herself can be relentlessly confessional when arguing a point about a certain film, she loathes that special contemporary glorification of personal data bared solely for the purpose of advancing celebrity. (Still, what could be more personal than the following from a Pauline Kael review: “When Shoeshine opened in 1947, I went to see it alone after one of those terrible lovers’ quarrels that leave one in a state of incomprehensible despair. I came out of the theater, tears streaming, and overheard the petulant voice of a college girl complaining to her boyfriend, ‘Well, I don’t see what was so special about that movie.’ I walked up the street, crying blindly, no longer certain whether my tears were for the tragedy on the screen, the hopelessness I felt for myself, or the alienation I felt from those who could not experience the radiance of Shoeshine. For if people cannot feel Shoeshine what can they feel?”)

One comes to realize, finally, that for Pauline Kael, writing film criticism is not only a chance to write about the way we live in this country at this particular moment. It is also, very often, a necessary act of protection. “You have to recognize what is important for the art of the movies,” she says. “The movies that have the big publicity budgets and the advertising, they will take care of themselves. I mean, the critic is the answer to advertising, mostly because the advertising protects. The critic is the only protection for the art of the film for which there isn’t a big budget and a lot of advertising. A movie like The Conformist is exactly the kind where you’ve got to help that director [Bernardo Bertolucci] keep working because he is a major talent. It was the same with Godard’s early films, or Bonnie and Clyde, or China Is Near, or Bob Altman—when Fox didn’t know what they had in M*A*S*H—or Fred Wiseman’s documentaries. If there’s a chance that you can help, you do. And so the deficiencies you minimize, I mean just instinctively. If you’re sane you just have to.”

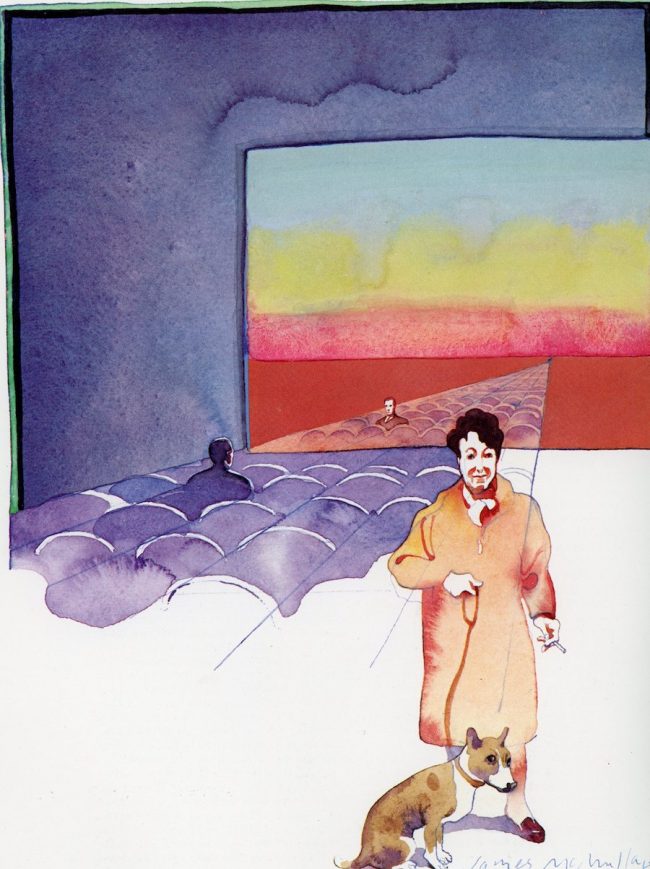

[Illustrations by James McMullan]