Shelley Winters has written the story of her life. Anyone who has followed her flourishing career on the talk show circuit will be pardoned for asking what she possibly has left to tell. The TV addict who really keeps track of these matters may wonder why the book comes to us at least seven years after we first heard about it. If you pay attention and don’t interrupt, she will try to explain.

“Lippincott gave me an advance, and I had just done my play off-Broadway, One Night Stands of a Noisy Passenger. They thought it was very autobiographical, and I said, ‘Of course it is, but the men are me and the women are me.’ I mean, everybody writes autobiographically. But unfortunately my life has been an open book, as it were, through all the columnists.

“Would you believe that I lose things I write? I wrote a book called Hansel and Gretel in the Oven. At the Actors Studio I wrote a thing called Albergo Primavera, which was sort of about the Hotel de Ia Ville in Rome in this horrendous period when I was staying there and Vittorio Gassman and I were getting divorced, and I can’t find them.

“So after the play, which was in 1971, I signed a contract with Lippincott to do an autobiography. And I made an outline. And I couldn’t write part one. I don’t know why. Writing about my mother and father, it just depressed me terribly. Oh, I have a trunkful of tapes that I did. Now I write in pencil and then can’t read it. I have to write in pencil. And I can type. I developed a system where I got a wonderful fast secretary, and she would come in at noon because I found that the best time for me to write is at one o’clock after Johnny Carson is over, to stay up all night when it is quiet and the phones are off. I cannot bear not to answer a phone. I always think somebody is committing suicide.

“Lippincott didn’t give me much money. I don’t know what I was going to do. I wanted to go to a spa. So they gave me $10,000. I have a bouncing-ball weight problem. It’s harder to lose as I get older. They gave me an outline. That was their mistake. I used to stare at it. Childhood. Early Childhood, two chapters. Mother. Grandparents. You know?

“I can’t follow an outline. It fouls me up. I think it was my agent who took the book idea to this publisher, Morrow. You know I wrote 1,200 pages? Ellis Amburn, my editor, worked out a system for me. He got it down to 450 pages, and they gotta sell the book for $15 and that’s just up to 1955. I have no idea how to deal with the rest. Anthony Franciosa [the last of her three husbands] would not sue me, he would kill me. I said to Ellis, ‘Why didn’t you tell me when you saw I was writing 1,200 pages?’

“I wanted to call it Mainstreams and Tributaries. You know, when I first wrote it Ellis said, ‘This is all tributaries and no mainstream.’ I start out telling a story and then something reminds me of something else and something else reminds me of something else. And I say, ‘Wait a minute. Where was I?’ ”

She was, at the moment of this ramble, stretched out on a couch in her New York apartment, doing battle with a stubborn case of flu and searching for a mislaid train of thought. Titles, titles. Oh, yes, titles. Winters also wanted to call her book The Myth and the Mensch, but Morrow resisted the Yiddishism out of the probably erroneous belief that there still a few people around who don’t know that mensch describes a large-hearted, mature, responsible, upstanding, thoroughly terrific sort of person.

In a profession that thrives on image-making, Winters doesn’t seem to know how.

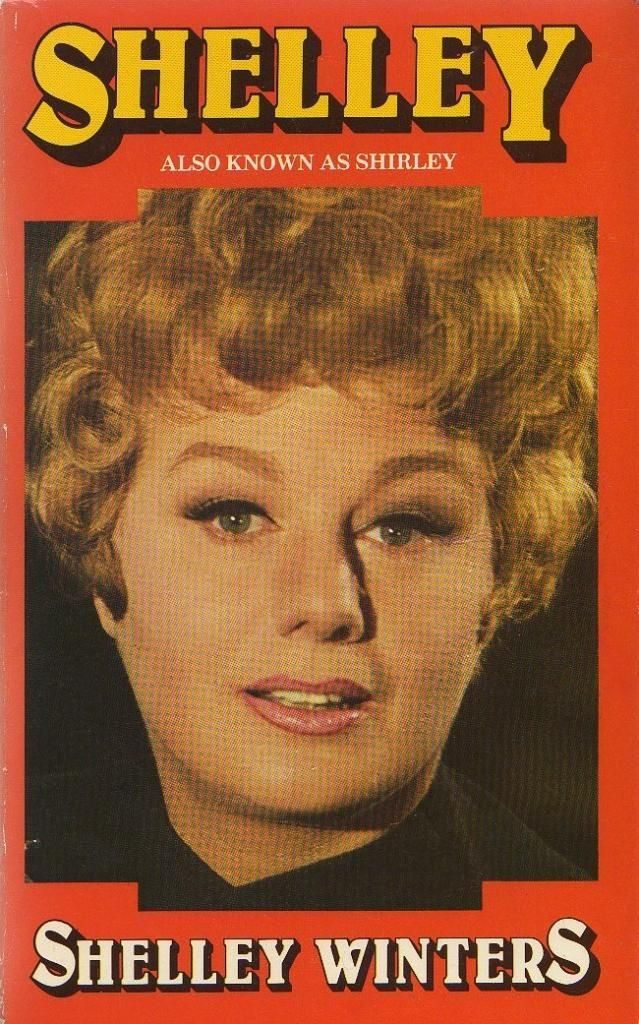

So the book comes to us as Shelley, Also Known as Shirley, which turns out to be a pretty good fit. Although she has answered to Shelley since she began haunting Broadway casting offices in her teens, she thinks of herself as Shirley. In Beverly Hills, Shelley Winters drives a white Cadillac; it’s a movie star car, and she’s owned a succession of models since the day she saw Elizabeth Taylor arrive at the studio in her white Caddy in 1949. In New York, on the other hand, the former Shirley Shrift, her eyes rheumy with fever, races to the budget department store Alexander’s on a Sunday to take advantage of the specially-priced opossum-lined trench coats marked down from $199 to $150 for one day only. Shelley owns three houses in California. Shirley, child of the Depression, still has the two sofas she bought at the Merchandise Mart in Chicago in 1941 while touring with a show. They have been reupholstered, of course. Several times.

Details of her parsimony were offered with faint self-mockery. What keeps her durable and bearable is a total lack of facade. In a profession that thrives on image-making, Winters doesn’t seem to know how. Like her book, she is noisy, gossipy, hearty, shrewd, funny, vulgar, blunt and engaging. In the absence of a camera, her round, smooth face had been left innocent of makeup and her streaky yellowish hair looked as if it had once known a comb but not intimately. Under a bright blue blanket, her feet were bare, her body encased in a tentlike black print garment. She was quite fat, but in preparation for her book tour, Winters was planning a sojourn at one of those go-hungry spas where Mallomars are interdicted. In a corner opposite her couch stood the real villain in her war on weight, a huge TV set. “It brings out the munchies in me,” she said, and then, in a seizure of self-analysis, mused, “Maybe it starves me artistically so I wanna eat.”

In this context, it is useful to know that Shelley Winters has probably been in therapy even longer than Woody Allen. Since their psychiatrists maintain offices in the same building, she runs into Allen sometimes on her way to a session. In all likelihood, their problems are dissimilar. Hers has been narrowed to one. “If I lose thirty pounds,” Winters said, “I graduate.”

Winters’s New York place is a modest apartment in a modem, high-rise building on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, behind a door with three locks. The rooms are furnished in a style best described as Early Clutter. There are family pictures everywhere. Chinese carpets, gloomy looking cabinets, acting awards, tired plants, and, on the walls, a lot of art, some good.

Yet Hollywood reposes one room away in the person of a woman called Mary; general factotums from movieland rarely have last names. Mary is secretary, chauffeur, companion, nanny and, today, it turned out, even cook. An afternoon with Winters is punctuated by sudden shrieks of MA-REE-EE-EEE, which brings the young woman calmly gliding into the parlor. Winters is accustomed to service. Important things must be remembered, important calls made.

Winters is also accustomed to having her way. Although she claims to have allowed her talent for combat to wither, she can still raise a memorable fuss. Final editing on her book took place at the Morrow offices, where Winters challenged every alteration in full voice. “What’s this? What’s this?” she demanded upon finding out that Amburn had changed “came out” to “emerged” because the former phrase appeared too often on a page. “ ‘Emerged?’ That’s not a Shelley Winters word.”

“I don’t understand the new generation of actors. They sit by the telephone and wait for the agent to call. If you sit around and turn down pictures, you don’t work.”

Amburn seems to have enjoyed every minute of the relationship. He made Winters an author by figuring out how to harness her disorganized vitality. “I sat and wrote on yellow pads,” Winters says, “a sort of stream-of-consciousness thing with no punctuation and never mind the spelling. Then the secretary would come and type it on pink paper, and I would take it back the next night and fix it and rewrite it with a lot of different pencils. Then the next day she would put it on orange paper, and I’d go over it again, and she’d retype it again.”

Is it any surprise that she produced such a colorful book? Winters got to Hollywood on a Columbia contract in the early ’40s when the studio system still held sway, and her account of the time is interesting and spirited. She was a fun-loving girl, appealing, zaftig and breathtakingly susceptible. Without notes, it is possible to lose count of her romantic adventures.

A veteran at the interview game, Winters expected to be asked whether she had any qualms about setting it all down and was ready for the question. “You know,” she said, “I don’t feel that when people pay $5 for a movie ticket, all they’re entitled to is what I give them on the screen.” As Winters sees it, Hollywood feeds America’s fantasy life in much the same way that the royal family feeds England’s, and the paying customer has a right to know what Robert Redford eats for breakfast and how Shelley passes the time of night.

To be sure, it hasn’t all been eggs Benedict and satin sheets. The book conveys real poignancy over the failure of her first two marriages. To her surprise, she found herself most upset and weeping as she summoned up the first, a wartime union with a Midwestern businessman who gets a pseudonym in the narrative “because he has grown children.” They married in 1942 when she was still a struggling Broadway performer; by the time he came back from the war four years later, she was a Hollywood starlet parading through a succession of “blonde-bombshell” parts and campaigning for more serious roles. On her right hand, she still wears his engagement ring, a 2.9-carat diamond. Of three former husbands, “he was the nicest,” she said. “He just didn’t want to be the husband of a movie star.”

She married Vittorio Gassman when she was a movie star as a result of A Place in the Sun and when he was one of the premier figures of the Italian theater. The union endured for about three years and produced her only child, Vittoria, now twenty-six and about to enter medical school. It ended in 1955 in a public rain of recrimination that established some kind of record for tastelessness. Vittorio had been playing around. But what really did them in were two acting careers separated by a continent and an ocean. They are good friends now, and have been since her divorce from Tony Franciosa, whom she came to know during the Broadway run of A Hatful of Rain. “A real rebound marriage,” she recalled. “I was so mad at Vittorio.” The wedding took place in 1957 and surprised everyone, including the bride.

Through good times and bad, Winters kept right on working. When film roles thinned out, she did summer stock. One season, she banked $3,000 a week traveling with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Another year, she toured with Born Yesterday, bringing it into Appalachia coal country for a dollar a ticket. She stopped counting when the number of her pictures passed 100. She still appears in more movies than many actresses of her generation—the record books say she was born in 1922—and credit, she feels, belongs to decades with “the shrink.” Some stars never adjust to third or fourth billing behind the latest fresh-faced twenty-three-year-old wonder.

Given her size and style, Winters winds up playing a lot of blowsy, sluttish matrons, sometimes forgettably in what amounts to frantic self-parody. But along the way, there have been some swell performances, among them as the mother in Lolita, the mother in A Patch of Blue, which brought her a second Oscar in 1965 (her first was for supporting actress in The Diary of Anne Frank in 1959), and the quintessential Jewish mother in Last Stop, Greenwich Village. As she memorably trumpeted in Wild in the Streets, while being carted off to concentration camp at the direction of her son. the twenty-two-year-old rock-star president, “I’m the biggest mother of them all.” This summer, working for Blake Edwards in S.O.B., she gets to impersonate a brash, beefy Hollywood agent who somewhat resembles the real-life agent Sue Mengers.

“My mother,” Winters reminisces, “used to say that if I didn’t have a job, I would rent a corner store and do a play in it. It’s true. I don’t understand the new generation of actors. They sit by the telephone and wait for the agent to call. I think you take the first offer. I really believe it. If you sit around and turn down pictures, you don’t work.”

Of course, there are things she will not do. “I do not do nude scenes. I’m very old-fashioned about this. Maybe if I were twenty-two with a great body and the script absolutely called for it, if I felt it lent something important. But I feel it shocks the audience. What was the play about horses? Equus. Why did they suddenly take their clothes off? It knocked you right out of the play. And I didn’t like what the play said—that people create through neuroses and if you’re healthy, you can’t be a creative artist.

“I’ve done a variety of things. Like I did a picture in England called Who Slew Auntie Roo. Everybody said, ‘What do you want to do this for?’ I did it because Ralph Richardson was in it. That picture now plays every Halloween. A whole generation of kids know me as Auntie Roo.

“I’ve made serious mistakes. I turned down $2,500 a week and two and a half percent of Hair, the off-Broadway production. They bowed nude at the end, and I didn’t agree with everything it said. Did you see Seven Beauties? Lina Wertmuller wanted me to play the part played by Shirley Stoler, the concentration-camp role. I would have done it better and different. I had two tickets to the last sailing of the Michelangelo for my daughter and myself, and then I got this script and I said, ‘I can’t spend eight weeks in a concentration camp. I’ll end up in the hospital.’ I’ve had wonderful scripts that came out terrible. Like I did The Magician. It had a wonderful cast. Alan Arkin, who’s a wonderful comedian, somehow decided to play this absolutely straight. I couldn’t believe it. I mean, the director should have been fired.

“The book is so juicy and funny. He had scenes where he talks to God, which were unbelievable. Can you imagine him refusing to do that? Refused. Wouldn’t do the scene. I told the director, Menahem Golan, this Israeli guy, I said, ‘You don’t direct any more.’ I said, ‘You’re a wonderful producer, but you do not know how to handle actors.’ He isn’t directing any more.”

But Shelley Winters is. When all else fails and she can’t find a corner store, there is always the Actors Studio, with which she has been associated for much of her adult life. A while ago. she directed a Studio production of the Edward Albee play, Everything in the Garden, and this past winter she was seriously talking about a low-budget Hollywood deal that would put her in charge of her first movie.

She is not, however, about to cease performing. In mid-flu, Winters was daily stubbornly rehearsing a studio exercise of Brecht’s Mother Courage, which nourished both her artistic needs and her finely-honed sense of outrage. Once famously active on behalf of some Democratic candidates, she finds politics “very confusing these days.” A trifle solemnly, she reports, “It’s one of the reasons I’m doing Mother Courage. Her philosophy is Take Care of Number One. That was in the Hundred Years War, you know. What happens when you take care of number one is that your own children can’t be safe if other children are starving and dying.”

At this stage of her life, one of Winters’s pressing problems is avoiding her old movies. Asked if she ever sees them, she fairly shouts, “Never!” Then she remembers that last year she was a reluctant guest of honor at a Shelley Winters retrospective, one of a series of film weekends held in Tarrytown by Judith Crist, the critic. “I had to sit there, like three times a day,” she wails, “and I had to watch myself get older and older and fat. It was terrible. I thought, ‘Oh, God, I’ll never do this one again.’ ”

Prodded, she will grant that it was a celebration of some things well done and that even she could muster a swell of pride at her professional past. But, snuggling under the blanket, momentarily forgetting that she is the author of a large, expensive volume of reminiscences, she confided that it was important to realize one thing: “When you come right down to it, my mind doesn’t go to the past at all.”