Flying west, through Texas, you leave Dallas-Fort Worth behind and look out suddenly onto a rolling, bare-boned, November country that stretches away to the horizon on every side—a vast, landlocked Sargasso Sea of mesquite-dotted emptiness. There are more cattle down there ranging those hazy, distance-colored expanses than people, and in turn, more people than timber topping out at five feet, for this is cowdom’s fabled domain, the short-grass country—yipi-ti-yi-yo, little pardners—the Land of the Chicken-Fried Steak, where if your gravity fails you among the shit-kickers, chili-dippers, and pistoleros, negativity emphatically won’t pull you through.

Below, there are few houses, fewer roads, and scarcely any towns. As the dun landscape slides past under the plane’s port wing, the overwhelming sense of the vista is solitude, and if you happen to hail from that iron killing floor down there, as I do, you begin to feel edgy and defenseless, moving across so much blank space and drenching memory.

The shuttle plane, an eighteen-seater De Haviland-Perrin, seems infernally slow after the rush of the Delta jet from San Francisco; its engines are loud, too, and it bucks around in the brown overcast between Dallas and Wichita Falls like a sunfishing busthead-bronc. Fitfully, I’m riffling through the pages of an underground sheet called Dallas Notes—“Narc Thugs Trash Local White Panthers”—but the lonesome countryside below keeps drawing my mind and eye away from the real-enough agonies of Big D’s would-be dope brotherhood. Somewhere down there slightly to the south, a pioneer Texian named William Medford Lewis—my paternal grandfather—lies buried in the Brushy Cemetery, hard by the fragrant dogwood trails of Montague County where he and I once tramped together in less fitful times. Beside him, that fierce, pussel-bellied old man I remember above all other men, lies his next-to-youngest son, Cecil—a ghostly wraith-memory of childhood, a convicted bank robber and onetime cohort of Bonnie and Clyde who was paroled from the Huntsville pen in 1944 just in time to die fifty-six days later in the invasion of Sicily—and beside Cecil, in turn, lies my grandmother, who once lifted an uncommonly sweet contralto in whatever Pentecostal church lay closest to hand.

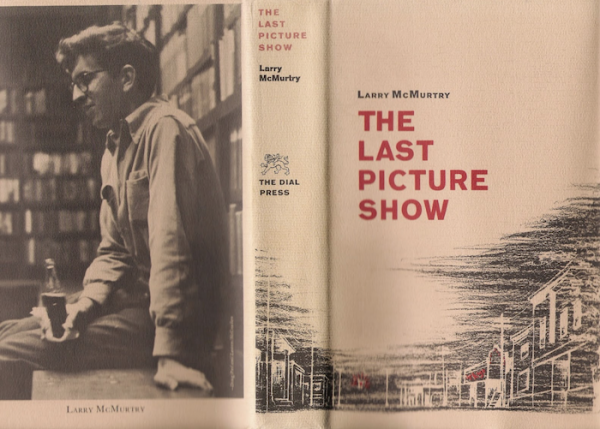

Somewhere down there, too, slightly more to the west, in a decaying little ranching hamlet called Archer City, a protean-talented young Hollywood writer-director named Peter Bogdanovich is filming Larry McMurtry’s novel The Last Picture Show in its true-to-life setting. McMurtry—Archer City’s only illustrious son—previously wrote Horseman, Pass By, from which the film Hud was made. Picture Show—there may be a title change before the film’s release, to avoid confusion with Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie—is to star Ben Johnson, Clu Gulager, Cloris Leachman, Jeff Bridges, and a couple of promising young unknowns, Timothy Bottoms and Cybill Shepherd. And, save us all, I’m to be in it, too, playing a small supporting part.

The Ramada Inn on the Red River Expressway, where the sixty-odd members of the Picture Show troupe are quartered, is big, seedy, and expensive, a quadrant of fake-fronted Colonial barracks overlooking a dead swimming pool and a windswept compound full of saw grass and cockleburs. “Hah yew today?” the desk clerk, a platinum-streaked grandmother in a miniskirt, trills cheerily as I check in at midafternoon.

My room—at least a city block from the lobby as the crow flies—is de rigueur institutional ugly, distinguished only by a tiny graffito penciled beneath the bathroom mirror: People who rely on the crutch of vulgarity are inarticulate motherfuckers. In sluggish slow motion, I stretch out across the bed to doze and await instructions from somebody in Archer City, forty miles to the southwest, where the day’s shooting has been under way since early morning. When the phone jangles a few minutes later, I snap alert, sweating, disoriented. Waking up in Whiskey-taw Falls storms my mind; less than twenty-four hours ago, I was bombed-and-strafed in the no-name bar in Sausalito.

Through a crackling connection and a babble of background din, the film’s production manager is shouting to ask what my clothing sizes are. “Peter wants you out here on the set as soon as possible,” he commands, barking out staccato directions of how I’m to connect with a driver who’ll fetch me to the location site.

Feeling wary and depressed, I wander downstairs and wait in the lobby. Christ, I haven’t done any acting I’d admit to since college, when I was typecast as the psycho killer in Detective Story. Now, I’m supposed to play “Mr. Crawford”—the village junkie-geek of Archer City circa the Korean War era, a character maybe twenty years my senior. More typecasting, I figure sourly.

The driver, a large, loose-limbed black man named James, lifts my spirits on sight. “Fuck them long cuts, ain’t I right, Grovah? l’ma take a short cut and git you to the church on time,” he announces, pumping my hand like a handle and grinning through dazzling silver teeth. On the way out of town in a Hertz station wagon, we pass the M-B Corral, a notorious hillbilly dive where, fourteen or fifteen years ago, Larry McMurtry and I stood among a circle of spectators in the parking lot one drizzly winter night and watched a nameless oilfield roughneck batter and kick Elvis Presley half to death in what was delicately alluded to afterwards as a difference of opinion about the availability of the roughneck’s girlfriend. McMurtry and I were wild-headed young runners-and-seekers back then, looking, I think, for a country of men; what we found, though, together and apart, were wraithlike city women in blowing taffeta dresses. And the shards and traceries of our forebears, of course, trapped in the stop-time aspic of old hillbilly records.

Out on the open highway, James stomps down hard on the accelerator and free-associates about his Army days to pass the time and the miles: “Twenty-two years in all I served in the arm service … I ony been back in Wichita, lessee, oh, about goin’ on three years now … Yeah, I seen action in World War II, in Korea, and in Veet-nam. Never kilt nobody, though, far’s I know, and never got kilt my own self, neither. Hah! … If it’s anything I despise to be in, it’s a conflick….I swear, this ol’ State 79 here, it’s the lonesomest stretch of miles I’ve ever drove, you know it? Sheeit.”

With a practiced snick, James spits out the window and falls silent. Beyond the weed-choked bar ditches paralleling the road, the stringy mattes of mesquite trees and stagnant stock tanks and the Christmas-tree oil rigs flash past at eighty mph under an unutterable immensity of hard blue sky. It is bluer even than I remember it, the sky, and I remember it as being blue to the point of arrogance, a galling reminder that it is harder to live in this hard-scrabble country than tap-dancing on a sofa in a driving rain. Up ahead, a rusty water tank towers over what looks like an untended automobile graveyard, and the .22-pocked city limits sign appears to identify the harsh tableau: ARCHER CITY—Population 1924.

The Spur Hotel, a rattletrap cattlemen’s hostel commandeered by the film troupe as production headquarters, hasn’t seen as much elbow-to-ass commotion since the great trail drives to Kansas in the Eighties. Throngs of stand-ins, crew technicians, bit players, and certified Grade A stupor-stars course in and out of the makeshift office like flocks of unhinged cockatoos. Phones ring incessantly; nobody moves to answer them. The location manager mutters into a walkie-talkie, and the agile-fingered men’s wardrobe master deals out seedy-looking Western outfits to a queue of leathery-faced extras like soiled cards from the bottom of the deck.

Making faces into the mouthpiece, the location manager does a fast fade on the field phone, pours a couple of cups of coffee, and broken-fields across the crowded room to say hello: “You play ‘Mr. Crawford,’ right? Far out, good to meet you….Don’t let this spooky dump spook you, hear? Looks like a rummage sale in a toilet, don’t it? Well, that’s show biz….As of this minute, Anno Domini, the production is—well, we’re behind schedule. Which means that Bert Schneider, the producer—you won’t meet him, he only feels safe back in Lotus Land—Bert’s begun to act very producer-like and chop out scenes. Peter just had to red-pencil the episode where the gang of town boys screws the heifer, and I hated like hell to see it go. That sort of material is disgusting to a lot of people, but, shitfire, man, it’s true-to-life. These hot-peckered kids around here still do that kind of thing as a daily routine. You’ve read McMurtry’s book, haven’t you? Why, Christ, to me, that’s what it’s all about—fertility rites among the unwashed.” Grinning amiably, he lifts his cup in a sardonic toasting gesture: “Well, here’s to darkness and utter chaos, ol’ buddy.”

Bogdanovich, a slight, grave-faced young man wearing horn-rims and rust-colored leather bell-bottoms, shakes hands in greeting, eyes my scruffy getup narrowly, and nods agreement; yes, he likes my ravaged face, too.

Polly Platt materializes out of the crush, her hands in her jean pockets, Bette Davis-style. A poised, fine-boned blonde with sometimes complicated hazel eyes, she is the production designer, as well as Bogdanovich’s wife. After an intense discussion with the wardrobe master about what constitutes a village geek, she coordinates my spiffy “Crawford” ensemble—baggy, faded dungarees, a shirt of a gray mucus color, and a tattered old purple sweater that hangs halfway to my knees.

Humming off-key, Polly waits while I change into my new splendor between the costume racks, and then the two of us stroll across the deserted courthouse square toward the American Legion Hall. She laughs with girlish delight as we pass the long-shuttered Royal Theater—The Last Picture Show in both fact and fantasy—and chats fondly about Ben Johnson, who’s already completed his part in the film and departed:

“He’s the real thing, Ben is—an old-fashioned country gentleman from his hat to his boots. Why, he didn’t even want to say ‘clap’ when it came up in dialogue. Peter and I were both flabbergasted. Later, I asked Ben about the nude bathing scene in The Wild Bunch. It turns out Sam Peckinpah had to get him and Warren Oates both knee-walking drunk to get the shot, which wasn’t in the original script….But Ben and Peter ended up working beautifully together. Wait’ll you see his rushes”—she gives a low whistle of admiration—“Academy stuff all the way, as they oom-pah in the trades.”

Inside the ramshackle Legion Hall—a confusion of packed bodies, snarled cables, huge Panavision cameras, and tangled mike booms and lighting baffles—Polly leads the way to a quiet corner and begins tinting my hair gray with a makeup solvent recommended to Bogdanovich by Orson Welles. In the crowd milling around the center of the hall, I single out Cloris Leachman, whom I’ve just seen in WUSA; Bogdanovich, head bent in intent conversation with cinematographer Bob Surtees, whom I recognize from a press book promoting The Graduate; Clu Gulager, foppish-perfect-pretty in Nudie’s finest ranch drag and manly footwear; and several teasingly familiar faces I can’t quite fit names to. Glancing our way, Bogdanovich smiles and waves to indicate that he’ll drop over to chat when he’s free.

“Orson may turn up down here, you know,” Polly muses as she dabs at my temples with a cotton swab. “The old rogue’s making a picture about a Hollywood director—Jake Hanniford—and as usual he wants to steal scenes from somebody else’s setup, if he can. Orson thinks Peter’s some kind of nutty intellectual, so he’s written him into the script in that sort of burlesque part. Peter says Hanniford’s going to be the dirtiest movie ever made….Whew, you sure get to know people fast, having to fool with their hair. Let’s see what you look like. Oh, fantastic, great! I like your face—it’s so ravaged. With the hair jobbie and those grungy old clothes, you look lunchier than Dennis Weaver in Touch of Evil.” Typecasting, I mumble under my breath.

Bogdanovich, a slight, grave-faced young man wearing horn-rims and rust-colored leather bell-bottoms, shakes hands in greeting, eyes my scruffy getup narrowly, and nods agreement; yes, he likes my ravaged face, too. “Just don’t wander out on the streets without a keeper,” he murmurs, deadpan. “I don’t want you getting arrested.” Motioning for me to follow, he strides briskly across the dense-packed room toward the camera setup, stopping along the way to introduce me to Cloris, Gulager, Surtees, Cybill Shepherd, and because she’s standing nearby, a pale, pretty young bit player from Dallas named Pam Keller. Finally, I make my shy hellos with Tim Bottoms, the tousle-haired, James Dean-ish actor who’s to play my estranged teenaged son in the upcoming scene: “Hi, son.” “Lo, dad.”

Oblivious to the racketing noise and movement around him, Bogdanovich blocks out our paces and patiently coaches Tim and me on our lines. It’s a muted confrontation scene the two of us are involved in, a long, Wellesian dolly shot set against the backdrop of a country-and-western dance. Tim and I rehearse our moves until Surtees signals Bogdanovich that he’s ready to roll; Peter, in turn, motions for Leon Miller’s string band, arrayed on a platform at the head of the dance floor, to strike up “Over the Waves.” The cameras whir; we go through the motions of the complicated shot twice. The second time around, it feels good. “Cut,” Bogdanovich calls. “Print both takes. Good work, everyone. Stel-lar!”

“Academy,” a disembodied voice bawls from behind a bank of glaring klieg lights.

Feeling washed-out and blank, I settle in a folding chair on the sidelines next to Pam Keller, who is “almost twenty” and who plays the part of “Jackie Lee French”—“Clu’s dancing partner,” she explains with a wry laugh, “which makes her a kind of semipro floozy, I guess.” As if on cue, Gulager wanders by with chat-up on his mind; playfully, he makes a feint at Pam’s ribs and bottom. “Oh, don’t be such a wimp,” she protests, frowning. Gulager, who speaks in a deep glottal rattle like Jimmy Stewart, gives her a pained look: “What was that you said, little lady?” “I don’t stutter, buster,” Pam snaps icily.

Dismissing him with a stare, Pam turns to ask what I do besides playing village junkie-geeks. Polly, who’s stood by watching the exchange, grins and flashes Pam the V-sign as Gulager stalks disgustedly away: “Way to go, sweetheart. He’s a real Hollywood showboat, that yo-yo.”

The interminable delays between takes stretch into hours that elide past like greased dreams. Late in the evening, Pam is saying, between polite yawns, that she absolutely adores books, particularly Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, and have I, by any chance, met Eric Hoffer, who she’s heard somewhere also lives in San Francisco?

Around midnight, the tedium shades off into stuporous exhaustion, and abruptly seven or eight of us are headed back to the Ramada Inn in an over-stuffed Buick sedan. Pam falls asleep instantly, looking frail and vulnerable enough to resemble somebody’s sister, maybe my own. To pass the time and the miles, Cloris and Gulager harmonize on old Baptist hymns, then trail off to silence. In the darkness beyond the swath of the headlights, the stringy mattes of mesquite trees and stagnant stock tanks and the Christmas-tree oil rigs flash past at eighty mph. Startled by the sight, I glimpse my bone-white hair and ravaged face in a window as I light a cigarette.

The conversation rises and falls desultorily. “Do we work tomorrow?” Gulager asks Cloris edgily. “Maybe we don’t work, huh? That’d be nice. I’d like to spend the day limbering up at the Y.” Cloris doesn’t know, shrugs fatalistically. “God, I’ve just been thinking about that gross asshole who plays my husband….This is the saddest picture,” she reflects with a wilting sigh.

The next day begins and ends with the ritual viewing of the dailies in the hotel’s cavernous banquet room. Sitting with Bogdanovich, who seems tense and distracted, and Bob Surtees, who is always medium cool, I watch enough footage to confirm Polly’s estimate of Ben Johnson’s performance as “Sam the Lion,” the dying proprietor of the Last Picture Show—he’s magnificent. Academy all the way. Then I hurry off to board the charter bus headed for Archer City.

On the hour-long ride to the set, I share a seat with Bill Thurman, who plays “Coach Popper,” Cloris Leachman’s husband in the film. Thurman, whose meaty, middle-aged face is a perfect relief map of burnt-out lust and last night’s booze, is kibbitzing across the aisle with Mike Hosford, Buddy Wood, and Loyd Catlett—Picture Show’s resident vitelloni. The term springs automatically to mind to describe the three randy young studs because, in essence, they’re playing themselves; on screen and off, they’re the high-strutting young calves of this short-grass country, always on the prod for excitement, and maybe a little strange to boot. Loyd, who is seventeen and something of a self-winding motormouth, is plunking dolefully on a guitar and munching a jawful of Brown Mule. “Terbacker puts fuel in mah airplane,” he explains expansively. “Say, look-a-here, Thurman, you seen our scene the other night—you thank we was any good?”

Thurman puts on a mock scowl and snarls: “Shit naw, kid, I thought y’all sucked—buncha little piss-aint punks.” “Hmph,” Loyd snorts, “that’s what that dollar whiskey’ll do to your brains, Ah guess.” Under his breath, he hisses: “Kiss mah root, you boogerin’ ol’ fart.” Without preamble, he breaks into the Beatles’ song about doing it in the road, and the other boys join in the singing with gusto, if no clear command of harmony.

“Me and Cloris are gettin’ along real good together in our scenes,” Thurman remarks, looking as if he’d give a princely sum to believe it. “I guess the production’s been a little bit disorganized up to now, but all things considered, I b’lieve we got a real grabber on our hands here, don’t you agree?” The vitelloni strike up “A Boy Named Sue,” and Thurman starts reminiscing about the various “stars and gentlemen” he’s had the privilege of working with. “Les Tremayne,” he says. The boys segue into “Don’t Bogart That Joint.” “Bob Middleton … Paul Ford….” Thurman intones reverentially. “They’re—gonna—put—me—in—the—movies,” Loyd is yowling as the bus pulls up at the Spur Hotel.

After changing into our costumes, Loyd and I walk over to the Legion Hall together. He says he wants to be an actor or maybe a stunt man—“for the money and the thrills … There’s flat nothin’ to do around these parts but fistfight and fuck, and Ah ain’t even got a girlfriend,” he laments. “Sometimes Ah feel lower than whaleshit, good buddeh, and that’s on the bottom of the ocean….Drama in high school—that’s the only thang Ah was ever any good at. That and rodeoin’, but mah folks made me give up ridin’ bulls ’cause it’s dangerous and they didn’t like the company Ah was keepin’. Now, though, Ah’ve got mah foot in the door to the movies—shit, son, Ah’m gonna make $1,600 on this picture just by itself—and all Ah gotta do is take the ball and run, don’t you thank?”

On the set, which is being busily readied for another take in the dance sequence, the wardrobe master sits slumped on a camp stool, firmly clutching the prop purse that Cloris Leachman will need in the upcoming scene. Striding past him, the first assistant director fakes an ogling double take: “Somehow, Mick, I don’t think it’s the real you—but would you be my bubeleh tonight?” The wardrobe master grins and lazily flashes him the bird.

“We need a huge container of water, Lou,” Bogdanovich calls out to the second propman. “Waterloo!” the first assistant director crows. “That’s what this whole deal is about, right?” “We hired Rube for his wit, not his talent,” Bogdanovich murmurs as he peers through a viewfinder.

The hall is chill and drafty; the first raw gusts of a blue norther are rattling the windowpanes and doors. I find a chair near a gas heater and sit down to scribble some notes. Nearby, Bill Thurman, Clu Gulager, and several extras are seated around a card table, playing Forty-two. “Pass, fade, or die, you mis’able sonsabitches!” Thurman keeps bawling. Pointedly ignoring him, Gulager asks his partner, a barrel-gutted oil rigger from Olney: “Are you fellows deep-bleed drilling? Are you draining off all the oil over there?” “Sheeit,” the rigger drawls, “I ain’t been dreenin’ off nothin’ lately, what with this recession got me by the short hairs.”

The second assistant director stops to survey the domino game for a minute. “Sweet baby Jesus,” he mutters, “if I ran into this bunch in Tarzana, I’d turn out the lights and call the law.”

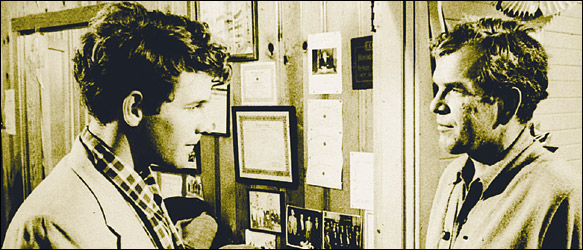

Timothy Bottoms with Grover Lewis.

Speaking of which, there’s Joe Heathcock, the lanky apparition who plays the county sheriff in the film, proudly displaying his prop .38 police special to John Hellerman, who portrays “Mr. Cecil,” a high school English teacher unjustly stigmatized as a homosexual. “My, oh, my,” Hellerman, a dainty-featured little man, keeps murmuring as Heathcock waves the pistol around airily, explaining that Texas lawmen don’t carry .45s much anymore—“That’s just what you might call a lingerin’ myth. They mostly tote these leetle ol’ boogers like this here now….Did I tell you? I just missed gettin’ hijacked to Cuba with ol’ Tex Ritter oncet. He tole me later they treated him like royalty down there—fed him a steak thick as a horse blanket.” “My, oh, my,” Hellerman repeats uneasily, his eyes keeping track of the gun.

Heathcock, I’m not surprised to find out, was famous long ago as “Jody” in Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys (“A-Ha! Come on in, Jody!”), and nowadays gigs around Hollywood, Vegas, and Nashville for an enterprising $2,500 a week. As he talks, his movements and gestures aren’t so much direct thrusts as sidelong indirections—furtive, elliptical—as if he’s swimming through syrup toward some improbable lover. I mark him down on sight as an all-around rara avis, this homely, likable old bird, and move in closer to listen as he launches into a scarifying yarn about getting tossed in jail in Bowie, a shirttail burg not far to the south of Archer City.

“Wellser, I was a drankin’ man back in them days,” he recalls, sucking fire into his pipe and cackling now and then with the force of an exploding boiler. “As I recollect it, I was drivin’ up from San Antone to Tulsa to meet Bob and the boys in the band, and I was about half-drunk—the last half, that is—hah!—so I pulled off the road and was gonna catch a leetle nap of shut-eye. Now, understand, I wasn’t nothin’ but a hahrd hand back then, but I had six-seven hunnerd dollars stuffed in my boot, so when somebody started shakin’ my laig in the middle of the night, why, I just natcherly kicked whoever it was flush in the face. Wellser, be damned if whoever it was didn’t turn out to be a Bowie constable, and he done the same thing right back to me—I left the better half of my teeth strung out along that highway when he brang me in to the lockup. Still and all, it was kiley a Mexican standoff—I shinered both of his eyes and bust his nose, too, before I realized he was a po-lice. Wellser, as it happens, that leetle set-to turned out to be a turnin’ point for me—I ain’t had a drank since, and that was right at twenty years ago. I figgered I’d been down so long it looked like it was all up to me at that point, so I—”

“But what happened?” Hellerman asks, jaw ajar.

“Happened?” Jody blinks. “Why, I awready told you. I quit drankin’.”

“I mean at the jail,” Hellerman persists.

“Oh, that.” Jody relights his pipe with the timing of a paid assassin. “Well, I got out with a leetle hep from some friends.”

Taking a few minutes’ breather, I sit down on the sidelines, idly thumbing through the pages of a paperback copy of the novel version of Picture Show (Dell, 75¢, out of print). Set in a grim, mythical backwater called Thalia in 1951 (and “lovingly dedicated” to Larry McMurtry’s hometown), the story focuses on a loose-knit clique of teenagers who have ultimately nowhere to go except to bed with each other, and to war in Korea.

The adults who alternately guide and misguide their young—even Sam the Lion, the salty old patriarch who rules over the town’s lone movie theater—are no less disaffected by the numbing mise-en-scène of Thalia; in Dorothy Parker’s phrase, they are all trapped like a trap in a trap.

The tenor of life in Thalia is described this way by a wayward mother to her soon-to-be-wayward daughter:

“The only really important thing I [wanted] to tell you was that life here is very monotonous. Things happen the same way over and over again. I think it’s more monotonous in this part of the country than it is in other places, but I don’t really know that—it may be monotonous everywhere. I’m sick of it, myself.”

As far removed from grace or salvation as the Deity is reputed to be distant from sin, the town boys haunt the picture show, where they’re permitted a few hours of “above the waist” passion with their girls on Saturday nights. Inexorably, boys and girls together careen into out-of-control adulthood in the Age of the Cold Warrior. But as they do, the symbols and landmarks of their childhood become lost to them, and in the end, even the picture show is gone.

Weighing the book in my hand, I try to weigh it in my mind as well—objectively, if possible. The narrative is sometimes crude, more often tasteless, and always bitter as distilled gall. But it is true—true to the bone-and-gristle life in this stricken, sepia-colored tag-end of nowhere. So it goes in the short-grass country. It’s hardly a thought to warm your hands over, but it occurs to me that I’ve been in Archer City only a scant few hours, and like that daughter’s mother in Thalia, I’m already a little sick of it, my own self.

“What previous movie work have you done, little lady?” Gulager asks Pam as they idle at their toe marks for the still-stalled dance sequence. Pam darts him a quizzical glance, decides his tone is neutral if not exactly friendly, and says that she was Charlotte Rampling’s nude stand-in in an unreleased picture shot in Dallas called Going All Out. “Charlotte who? Never heard of her,” Gulager shoots back, not neutral after all as he bends over to dust off his hand-tooled boots with a handkerchief. “Oh, you know—that girl in The Damned,” Pam stammers, looking flushed. “You saw The Damned, didn’t you?….I remember seeing you in The Killers with Lee Marvin. I thought you were—really quite good in it.”

Gulager smiles crookedly and tucks the handkerchief back in his pocket: “Everybody thought I was good in that one, including me, honey. It was made for TV, and I expected to win an Emmy nomination for it. Turned out, the picture was too violent for family viewing and none of the networks would touch it….” Gulager pauses, then spits out coldly: “I hate acting, anyway—despise it. San Francisco International on NBC this season—you seen it yet? Don’t bother. It’s a piece of fuckin’ trash. I’m only working on that series and this picture for the money. My main drive from now on is to become a filmmaker. Control—that’s the only thing worth having in this business.”

Unsure what to reply, Pam clears her throat and delicately observes that Gulager sounds a lot like Jimmy Stewart at certain odd moments. Gulager laughs shortly: “I wish I had Stewart’s money.” “Oh, money’s not everything—” she starts to scold. Gulager cuts her off: “I can’t think of anything I want to do that money can’t buy. Money buys talent. Talent makes movies. I want to make movies. It’s that simple.”

Up on the rostrum, Leon Miller’s string band—two guitars, a bass, and a fiddle—saws away wearily on “Put Your Little Foot” as the two assistant directors supervise endless dance rehearsals. A grip threads his way across the dance floor, bawling, “Hot stuff—comin’ through.” The box he’s carrying is marked: DON’T TOUCH—PROOFS TO TUESDAY’S SHOOTING. As they advance one-two and return three-four, Gulager and Pam continue their muted bickering until finally he flares up and calls her a “know-it-all little shit.” Eyes snapping, Pam tartly informs him that you have to be a little shit before you can be a big one—“Ness pah, Big Shit?” Out on the floor, one of the extras faints, and there’s another long delay. Pam wanders over to the sidelines, looking flustered. Jody, strumming Jeff Bridges’ gleaming D-28 Martin, serenades her, Jimmie Rodgers-style:

If I can’t be yo’ shotgun, mama

I sho ain’t gonna be yo’ shell

Pam blushes pleased pink and mercurially changes moods. Maneuvering around to catch a glimpse of my notes, she puts on an impish smile and cajoles in an orphan-of-the-storm falsetto: “Oh, make me famous, will you, please? Are you famous by any chance? Clu Gulager is famous, you bet. He’s famous-er than anybody, in fact. Just ask the rat bastard.”

Near one of the too-few heaters scattered around the hall, Bob Glenn, who plays a nouveau-dumb oil baron in the film, is remarking that he appreciates the unstructured makeup of the location company—“No snotty star types, all the lead actors mingling with everybody else.” Fred Jackson bobs his head in agreement: one of the stand-ins, he’s a tall drink of water from over Throckmorton way who looks uncannily like Buck Owens. “Hail yes, Bawb,” he says. “So far, ever’body high and low’s just acted like we’us all in this thang together, you know what I mean? Dju meet ol’ Ben Johnson while he’us down here? Shit, he’s just folks, that ol’ boy. He’s sposed to come back one a these times and go huntin’ with me. You ever do any huntin’?”

Looking sulky and bored, Loyd Catlett saunters past and overhears Jackson’s question. “You damn betchy Ah go huntin’,” he grumps, “but that don’t mean Ah never ketch nothin’. Same thang with this picture—Ah missed out on all the good parts. Ah never git no pussy, and Ah don’t git in no fights. Ah’m just a kind of sidekick for Jeff and Tim, Ah guess.” “Well, I reckon you just got to keep on keepin’ on, boy,” Jackson says affably. Loyd can’t maintain his pout for long. Soon, he’s grinning toothily despite himself: “Aw, slap hands with me, you sorry hillbilly dip-shit. Rat-on!”

Over an electric bullhorn, the first assistant director booms out: “All right, everybody be of good cheer. All together now, let’s have some SMILES!” “Let’s have some liquor,” somebody groans in reply. Scowling distractedly, Bogdanovich kicks at a thick hummock of recording cable. “Let’s have some lunch,” he sighs quietly.

Cybill blows the take by missing her mark parking the convertible. When she stammers out an apology, the sound mixer stage-whispers gruffly: “Sympathy can be found in the dictionary between shit and syphilis, sister.”

With manic zest, Gulager titillates the townspeople dining at the Golden Rooster, Archer City’s lone indoor eatery, by pasting pats of butter on his cheeks and forehead. “It wouldn’t melt in your mouth, honey,” Cloris observes acidly. Cybill Shepherd, who plays “Lacy,” the film’s teenaged sexpot, looks pained at the buzzing commotion Gulager is causing among the diners; wordlessly, she picks up her book—Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain—and leaves before the meal is served. It’s an interesting choice of reading and an interesting reaction; I determine to try to talk to her if a chance arises.

A local filling station owner approaches the table and shyly asks Gulager for his autograph; the big, sunburned man pretends not to notice the trickle of butter oozing down the actor’s jaw. Not to be overlooked in the crowd, Cloris launches into a rambling singsong recitative about George Hamilton taking a sleeping-pill suppository during a cab ride in Paris. She projects the maybe-apocryphal story just like an actress, but she breaks just like a little girl when nobody but Jeff Bridges laughs at the punch line. Gratefully, she tousles his hair: “Give my love to your daddy, Jeff-boy. Is he still all water-puckered from Sea Hunt?” Jeff grins bashfully and mumbles something into his plate.

Gulager, milking the butter schtick to the last drip, scrapes the runny yellow goo off his face and spreads it on a slice of bread, then wolfs it down with extravagant gusto. To a man, the diners across the crowded room crane around to watch his every move, but nobody quite applauds.

Pam, who’s sat rigid with distaste throughout the meal, looks pensive during the two-block walk back to the Legion Hall. “Clu Gulager,” she announces at last in a tiny, constricted voice, “is just another pretty face. All smeary with butter, at that. Blechh!” She reminds me of someone, Pam does. Like Loyd, in his way, and Jody, too, she reminds me of everybody decent I ever knew in this empty, perishing, hard-scrabble country.

Back on the set, the crew members are beginning to trundle the monstro Panavision equipment out into the parking lot where the night’s shooting is to take place. By this time, it’s 6:30, dark as the grave, and biting cold. Jody is warming his hands over a feebly flickering heater. “You awder this bad weather, darlin’?” he teases Pam. The prop master wanders among the clusters of actors and extras huddled around the stoves, asking, “Has anybody seen a can of snow?” General laughter trails him around the room. The chief camera operator is telling a spectacular-breasted teen queen from the neighboring town of Electra about working on Drive, He Said. “Well, it was a weird experience, I tell you that, sugar. Jack Nicholson’s what they call far out, you know? Dope and rebellion, all that shit. Me, I’m more or less a law-and-order person myself, so I told him after we saw the rough cut: ‘Jack, it’s a cute picture, but it’s not anything I’d want to take my wife and kids to see.’ Listen, uh… Dottie….I’ll probably have to work here until pretty late, but, uh … what’re you going to be up to around midnight?”

Loyd Catlett rushes in with the news that the generator truck has caught on fire. “The lost picture show,” Mae Woods, Bogdanovich’s secretary, groans, dashing outside to take a look. Fred Jackson grasps Loyd’s elbow and probes for his funnybone: “You hear about that ol’ hippie kid, he got the first asshole transplant?” Loyd shakes his head: “Naw—ouch, you sombitch!” “It re-jected him,” Fred guffaws. On a rump-sprung sofa near a fireplace that doesn’t work, Jody strums patient accompaniment while Cybill Shepherd and Jeff Bridges try to remember the words to “Back in the Saddle.” A rash of new domino games breaks out around the fires.

Outside, towering floodlights illumine the ’52-vintage cars ringing the entrance to the hall. The minor generator blaze has already been dispatched by the Archer City Volunteer Fire Department, some of whose members remain behind, striking stalwart poses. As usual, the shot Bogdanovich plans is diabolically complicated:

(1) Cybill, as “Jacy,” is to park her ’48 Ford convertible near the hall’s entrance, get out of the car, and be greeted by Randy Quaid, who plays “Lester,” a goofy-looking idle-rich suitor. They’re to exchange a page or so of dialogue before (2) Jeff and Tim Bottoms, as “Duane” and “Sonny,” respectively, barrel into the parking lot in a battered Dodge pickup against a moving frieze of extras shown in deep focus getting out of cars, walking across the lot toward the hall’s side entrance, etc. Tim exits from the truck toward the rear door while Jeff advances to embrace Cybill. During the clinch and subsequent dialogue, the camera pans around to show (3) Clu Gulager, as “Abilene,” escorting Pam Keller—“Jackie Lee French”—through the front door.

“All of that in one so-called fluid take,” the dolly operator groans piteously. “Hell, Peter, it’s not only difficult, it’s impossible.” “With patience and saliva,” an electrician pronounces sagely, “the elephant balleth the ant.”

“Peter, can we shoot this shit?” the boomman screams out from overhead. “Or not?” “Strictly speaking, Dean,” Bogdanovich mumbles, squinting at the setup, “possibly.” He motions toward the first assistant director: “Meester Rubin I theenk it iss time ve vill take a live vun.” “Damn, Peter,” the second assistant director snorts, “you’re getting to sound just like Otto. That prick.” “Ready when you are, C. B.,” shouts the first assistant director.

In a sudden hush, the cameras begin to roll, but Cybill blows the take by missing her mark parking the convertible. When she stammers out an apology, the sound mixer stage-whispers gruffly: “Sympathy can be found in the dictionary between shit and syphilis, sister.”

After the eighth consecutive take has gone down the tube—this time because Jeff has rammed the pickup into the side of the building—Bogdanovich murmurs though blue lips, “Well, back to the old drawing board.” “We’re as shit out of luck tonight as a barber in Berkeley,” the key grip grumbles. Polly Platt wanders around looking worried-in-general; Fred Jackson pats her on the shoulder in paternal commiseration. “Ain’t a horse that can’t be rode,” he philosophizes solemnly, “and ain’t a cowboy that can’t be throwed.” “Our l-left foot doesn’t seem to know what our other left f-foot is d-doing tonight,” Polly complains through chattering teeth.

Down on the shoulder of the highway, where despite the cold a sizeable crowd has gathered to watch the filming, a bandy-legged cowboy and his woman—both drunk—are quarreling bitterly about money. “Aw, hush up about it, honey,” she snaps, reaching for his arm. “C’mon—less you and me vamanos a casa. Piss on a buncha movie stars, anyhow.” “Naw, goddamnit!” he cries in a strangled fury, bristling away from her and fishing feverishly through his pockets. “I ain’t about to haul-ass home till we get this thang settled, oncet and for all! Here, goddamn your bitchin’ eyes—here’s 99 cents in change. Put a fuckin’ penny with that and you can buy a dollar anywheres!” Starting to sob, the woman slaps the change out of his hand and stumbles off into the darkness. After a minute, the cowboy spits toward the coins scattered in the gravel and sways off after her, howling: “Hey Trudy! Wait up a goddamn minute! I’m comin’, darlin’!”

It’s a wrap at last on what must be the eleventh or twelfth take. The actors and crew look numb and gray-faced with exhaustion; Pam looks distressed, as well. Her face is wind-chapped, she has a big red bump swelling on her forehead, and she’s worried sick that she may lose her receptionist’s day-job at the Royal Coach Inn in Dallas because Bogdanovich says he needs her for an additional day’s shooting. “I didn’t count on this movie changing my whole darn life!”

The troupe works till the midnight hour, then falls apart like some hydra-headed beast sawed off at the knees. In a station wagon speeding back to Wichita Falls, Gulager asks Jody how he happened to get involved with Picture Show.

“Wellser, ol’ Reba Hancock, Johnny Cash’s baby sister, she recommended me for the part,” Jody answers, tamping his pipe. “She’s a darlin’ woman, Reba is. You know her by any chance?”

Gulager leans forward, interested: “No, but I’ve met John. Worked on a benefit with him once: Has he cleaned up his act, like they say? Is he walkin’ the line these days?”

Jody grins broadly: “Aw, you bet yore sweet ass he is. Ol’ John’s livin’ real good now, real straight. I recollect he tole me oncet that he used to take up to a hunnerd pills a day—you know, what they call them, uppers? But that’s all spilt milk under the bridge now….Yep, John’s just bought hisself a nice home over at Nashville from Roy Osborne—and, a course, he’s got June, too, which that leetle ol’ girl has just done wonders for his health and his life.” “Is that where you make your home—Nashville?” Gulager asks.

“Yesser,” Jody nods, “and mah own self, I couldn’t be happier noplace else in the world. Shoot, I got more work comin’ in anymore than I can get around to, seems like. I’m a reg’lar member of the Grand Ole Opry, I work on Gunsmoke three-four times a year. The Mills Brothers just recorded a leetle ol’ song that I wrote—‘It Ain’t No Big Thang’—and I seen just the other day in Cashbox, I b’lieve it was, where that sucker’s awready in the Top One-Hunnerd.

“Hell’s bells, I had to flat up and quit Hee-Haw—it’us too corny for my sights, you know what I mean? Buncha sorry, white-trash mow-rons settin’ around on the floor cuttin’ up like fools. Then, too, Junior Samples, he’s got a terrible drankin’ problem, and not much sense to start with, and I got sick and tahrd of readin’ his idiot cards for him….But, y’know, that eggsuckin’ show shot up to 15 in the Nielsens last week, and John Cash’s fell off to 65. Somebody’s givin’ John some bum goudge on per-duction, seems like to me….

“Yesser, I lead an awful full and happy life these days. Play goff every chancet I get. I shot a few rounds with Dean Martin not long back. You know Dino, by any chancet? Well, Iemme tell you, he’s a fine ol’ boy—he wants to record in Nashville sometime soon. And Frank, y’know, he’s awready got studio time booked over there.”

Gulager coughs delicately: “That’s… uh, Sinatra you mean?”

“Yesser,” Jody nods, sucking serenely on his pipe, “that’s the one.”

During the postmidnight screening of some late-arriving rushes in the hotel’s banquet room, Bogdanovich, Polly, Bob Surtees, and six or seven other production aides drowse through some routine interior establishing shots, then snap alert at a brace of electrifying takes showing Gulager, as “Abilene,” seducing “Jacy”—Cybill Shepherd—in a deserted pool hall. Even in its unedited form, the scene has a raw and awesome power; at one point, Golager’s right eye, slightly cocked, gleams out of the eerily lit frame like a malevolent laser beam. “Academy,” the first assistant director murmurs reverently in Surtees’ direction. “Wow—Clu looks positively ogreish,” the second assistant director crows in delight. A brittle female voice pipes out of the dark at the back of the room: “Nothing that mental and spiritual plastic surgery couldn’t cure, honey.”

I spend the better part of an hour the next morning reviewing the reactions of some of the local gentry to the filming of Picture Show on their home turf, as expressed in letters to the editor of the weekly Archer County News. These are heartfelt communications, I’m given to understand by a hard-drinking production secretary, from “Baptists and worse.”

From the paper’s October 22, 1970, edition:

… I understand that (Larry McMurtry’s) book, if it can be called that, is to be translated into a movie and that portions are to be filmed in Archer City with the support and approval of the Citizenry. No doubt, a certain glamor and glitter is to be anticipated from having a few Hollywood types in the city during the filming, and perhaps some economic benefit may ensue, but if the City Dads and the School Board Members have taken the precaution to read the book, then no question can prevail as to the type of movie that will result. I, for one, feel that Archer City will come out of this with a sickness in its stomach and a certain misgiving about the support the City is lending to the further degradation and decay of the morals and attitudes we foist upon our youth in this Country…

Where are the voices that should be raised in opposition to this travesty?

Wake up, Small Town America. You are all that is left of decency and dignity in this country…

Yours truly, Noel W Petre

In the November 5 edition, the publisher, Joe Stults, mills about smartly over the issue in a signed column called “Joe’s Jots”:

Let me be fast to point out that I do not endorse or purchase dirty or obscene books, nor do I attend or endorse dirty movies. Neither do I consider myself a literary or movie critic. I must admit I have read only a few excerpts from the book and from what I read the book “stinks.” However, on the other hand, a Wichita Falls school teacher (woman) told me that she has read all of McMurtry’s books and thought they were tops…

I definitely cannot see where Archer City will suffer a “black eye” for permitting the movie to be filmed here. It has already proved to be an educational experience for many and if our morals are affected by this book or movie then maybe we need to cultivate a little deeper.

Later in the morning on the set in Archer City, the cast assembles and waits fretfully for the final hours of shooting on the dance sequence to begin. Polly Platt, renewing the tint job on my hair, is saying from behind her enormous blue oval shades: I was a Boston deb—can you believe it?—so I had a different notion about dances when I first got here….Now, I’m miserable and deliriously happy at the same time. I miss my baby girls to the point of pain—they’re with Peter’s family out in Phoenix—but I’m elated about the way the movie’s coming along….Of course, part of the agony is that Peter is no longer my friend or lover or companion; Peter is making a movie….He has a terrific nostalgia for his teenage years in the Fifties—Holden Caulfield ice-skating at Rockefeller Plaza with wholesome young girls in knee socks, like that…. Somehow, he’s managed to transfer those feelings about his own adolescence to the totally different experience of the kids in the film….Have you noticed? He’s very tender with the young actors…. So, I ended up ‘doing’ Cybill—her overall appearance as ‘Jacy’—to lock into those longing fantasies of Peter’s. In reality, I created a rival for myself, I guess….Well, anything for art, huh? There, now—you look properly geekish again. Get out there and wow ’em, kid: Win this one for the Gipper.”

“Who’s the Gipper, coach?” Cloris inquires brightly, making room for me in the shivering circle massed around a heater. Nearby, one of the never-ending Forty-two games is in progress, generating more heat than the stove. John Hellerman is dourly predicting that Mae Woods, Bogdanovich’s secretary, will turn pro and start hustling in the L.A. domino parlors when she gets back home. “Forty-two again!” Mae squeals, flashing Hellerman a deep-dish grin. Chording Jeff’s guitar from his perch on a prop crate, Jody serenades Ellen Burstyn, who plays “Lois,” a cynical, bed-hopping socialite in the film:

Sick, sober and sorry,

Broke, disgusted, and blue.

When I jumped on that ol’ Greyhound,

How come I set down by you?

By the fake fireplace, Bob Glenn is recalling the years he spent working in a repertory group in a remote area of Canada: “Only the National Geographic reviewed us,” he concludes ruefully. When I laugh, he sidles nearer and asks out of the lower half of his mouth if I’m holding anything “interesting to smoke from Frisco.” I give him a puzzled look; he looks at me as if I’m peculiar, too, then turns away to listen to Bill Thurman, who’s describing his lady agent in Dallas: “Gawddamn, boy, her fuckin’ laigs look like a sackful of doorknobs, and they run clear up to right under her tits. Shit, I can’t figger out atall how her ol’ man ever gets any.” Later in the day, I do a double take when Bogdanovich, who’s been standing within earshot, incorporates the remarks almost verbatim in a colloquy between the character “Coach Popper” and his beer-guzzling cronies.

“Domino contingent,” the first assistant director rasps over a bullhorn, “please hold it down to a roar. We’re having a rehearsal.” Warmed up by now, I stroll around for a while among the extras. Most of the men are unsmiling, stiff-starched, gleaming with brilliantine. The women, as a hard rule, are pinch-faced, mean-spirited cunts who make me wonder how I managed to couple with their spitting images so long without turning raving queer. Near the coffee urn, Gulager, his concho-studded hat tilted forward rakishly, is chousing a couple of the younger, prettier ones: “You got a boyfriend, do you, sugar? And you, too, hon? Back in Alvarado? Wahl, what do those two lucky ol’ boys think about you pretty little things bein’ way up here all by your lonesome makin’ a moom pitcher? Wahl, wahl, wahl….”

Over by the bandstand, where Leon Miller and his boys sit slumped like zombies after having played “Put Your Little Foot” for approximately the 527th time, Loyd is dogging the heels of the casting director. “Ah heard they gonna aw-dition three nekkid girls from Dallas today,” he whispers to me with a wink, “so Ah’m ona see if ol’ Chason’ll let me sneak a little peek.”

It’s a moment of truth for Pam, too, who’s just had a long, nerve-rattling talk on the phone with her boss in Dallas. While Bogdanovich blocks out the paces of her final scene with Gulager, Thurman moseys by, notices her woebegone expression, and asks, not unkindly: “Whatsa matter, sugar? You look like somebody cut yore piggen strang.” Pam makes a fetchingly grotesque face at him, but doesn’t answer. “Yeah, Pam, what’s up?” Bogdanovich prods with fond amusement. “You gonna get fired or what?” “I don’t know!” she bursts out, an oyster’s tear away from real tears. “A fat lot you care, anyway, Mr. Bigtime Director—you’re making a movie, right? The show must go on, right?” “Right,” Bogdanovich says evenly, turning away. Polly, who’s been following the conversation, bites her lip but says nothing.

“Hell, Pam, you think you got problems,” Thurman interjects gloomily. “Today’s mah birthday—I’m fifty years old. Syrup just went up to a goddamn dollar a goddamn sop.” “That so?” Gulager asks, flicking imaginary specks of dust off his glove-tight trousers. “I’ll be forty-two this month myself. But that’s all right, I guess—Antonioni was thirty-eight before he directed his first feature.” Polly makes a deep, gagging sound in her throat that Gulager pretends not to notice.

Out on the dance floor, Bogdanovich has a setup at last. When the actors are all in position, he sings out: “This is a take, folks. Movies are better than ever! Roll ’em!”

“Mark it,” the sound mixer growls.

“Five-nine-charlie-apple—take one,” a grip intones, clapping a slapstick.

“And … dancing!” the first assistant director booms out.

It’s a wrap in one so-called fluid take, and the crew lustily yodels its approval: “Way to go, Pam baby!” “Academy!” “Nice work, Clu.”

Over on the sidelines, where Pam goes to fretfully await transportation to the airport in Wichita Falls, a spry old lady from Vernon in a bird-nest hat is reminiscing about her honeymoon on the Goodnight Ranch in 1923; wearing a new fur coat, she tells Pam with a wan smile, she lost her footing crossing a fence stile and sank neck-deep in a snowdrift. “My swan,” she marvels in remembrance, “it took four big drovers to pull me a-loose. Of course, it got much colder in those days than it does now—”

Straight-arming her way up close, a blue-haired matron of fifty-odd in a psychedelic-splotched pantsuit interrupts to ask Pam: “Hay yew today?” “Just fine, thank you.” “Listen, can I git your autograph, dumplin’? You do play ‘Jacy,’ don’t you?” “No, ma’am, I play ‘Jackie Lee French’—” “Aw, well,” the woman sniffs, “that’s about as good, I gay-ess.” Looking stricken, Pam signs a paper napkin, then quickly scratches off her home phone number on a sliver of envelope and hands it to me. “If you happen to see the rushes I’m in,” she blurts, “call and let me know what you think, would you? I’m not sure I ever want to be in any more movies, but I’d like to know if I did good or not in this one.” Hugging Polly good-bye, she hurries off after a driver who’ll take her the first leg of the way back to Dallas.

Loyd watches Pam leave, then turns to Polly: “She say she don’t wannabe in no more movies? Is that what she said? Sheeit, boy, Ah do! Ah’d lahk to be in about a million of ’em.”

“Hush, Loyd,” Polly says in an absent tone.

Feeling twitchy and fogged-out, I cash in my costume early and hitch a ride back to the Ramada Inn in Bill Thurman’s blue Lincoln. Bob Glenn takes the wheel next to Gulager, while Thurman stretches out over most of the backseat, drinking what he calls “toddy for the body”—Old Taylor out of the bottle.

Between jolts, Thurman is gossiping about a Dallas-based sci-fi film impresario for whom he’s worked in a total of thirteen Grade Z pictures: “Ol’ Larry’s a good ol’ boy, you understand, but he cain’t keep his peeker out of his pocketbook.” Pause for a deep swallow. “’Course now, Mr. Bogdanovich … you know, Peter … he’s somethin’ else altogether, cain’t you agree, Clu?” Every time Thurman addresses Gulager, he calls him “Clu”; sometimes at both ends of the sentence.

Gulager, slumped in the front passenger’s seat, doesn’t deign to answer at once. Thurman goes on: “I mean, to me, I thank he’s got the makin’s of, uh, well … a great artist, maybe.” “Meb-be,” Gulager concedes, sounding unconvinced: “Personally, I don’t like the script cuts he’s making, but I guess he doesn’t have much choice about it. I’m gonna fight for that scene of yours in the gym, Bill—you know, where you tell the boys they’re too ugly to be girls and too short-peckered to be men.”

“Clu, would you do that, Clu?” Thurman entreats softly. “Gowddamnit, ol’ buddy, I shore would appreciate it, Clu.”

“Well, I don’t have any real power to do anything,” Gulager snaps irritably. “I’m just another Okie from Muskogee, myself—just another hired hand working for day wages—”

Bob Glenn cuts his eyes off the road an instant: “You really from Muskogee?”

“Tahlequah,” Gulager says, “twenty-nine miles outside…. But shit, look, Thurman, that’s the only reason I took my role—which is a fat zero of a nothing part—because there was a lot of other good stuff in the script. It read good to me, it read honest. As to whether Mr. Bogdanovich makes it or not, that pretty much depends on how this picture comes out. Both of you guys work mainly out of Dallas, right? Well, I make my living in Hollywood, and they write you off quick if you fail in my city.” The cutting edge of finality in his voice is chilling. Glenn suddenly brakes the car up short; a herd of high-stepping whiteface cattle stream across the highway. Thurman tips up his bottle for a long instant. Abruptly, it is spectral dark, and the night’s chill is on us all.

San Francisco International is on TV that night. I watch part of it in my room, then drift off to the hotel bar to belt back a few healing brandies. Gulager was square on the money in his estimate of the show; with lines like “A killer in an airport full of emotional people is a bad situation,” it’s a disaster area looking for a landing site. Half-tight, I vow soberly never to broach the topic to him. Later, on my way to bed, there’s a phone message for me at the desk from the Yankee Lady out in California: Sleep warm. After a bit, I do just that, dreaming at some surreal point that I’m Dennis Weaver in Touch of Evil, only Touch of Evil has somehow become a Saturday-afternoon Western playing at the Last Picture Show in Archer City—the old shuttered Royal Theater—and my grandfather and I are sitting in the hushed dark alongside—who’re those two ol’ boys in the seats next to us?—Larry McMurtry and Elvis?—yes—and suddenly my own ravaged face swims into focus on the silvery screen, bigger than life, and the camera pulls back to show me tap-dancing on a sofa in a driving rain while Bill Thurman, Bob Glenn, and Clu Gulager ping away at my feet with six-shooters. My grandfather leans forward as the scene unreels, lifts one liver-speckled old man’s hand as if to greet his own surprise, and says with an expiring sigh: “Academy, boy. Academy all the way!”

The next day’s call sheet lists the setting to be used as EXT GRAVEYARD, and summons all the principals of the cast and crew, plus “20 atmos. mourners,” a location van, the generator truck, a bus, two station wagons, the director’s car, and one (1) Ritter wind machine to the Spur Hotel at 9:30 sharp. From there, the assembled caravan will converge on the Archer City Community Cemetery, where the funeral of “Sam the Lion” is to be shot.

The Archer City cemetery, a barren but neatly tended tract with a few knobby trees jutting up here and there, forms a strong, stark tableau, so devoid of ornament that each stone and plant and ruptured fissure of the land plays an intense part in the composition, subtly forcing the eye out to the horizon and up to the sky. The weather, fortunately for Bogdanovich and us all, has turned mild, almost balmy, and the wind from the sea of mesquites to the west soughs along the yellow, grassy swell that ascend in all due homage to the burial ground’s only imposing structure—the Widow Thylor’s marble-columned crypt, with twin potted cactus plants flanking the door like spikey tribunes. As the actors file off the bus and mill curiously about a freshly dug grave to be used in the scene, the first assistant director unslings his ever-present bullhorn and intones solemnly: “Let us now praise famous men, ladies and gents. Welcome to Lenny Bruce’s cafeteria.”

Bogdanovich sets up the master shot of the funeral scene with uncommon speed, but close-ups and dialogue fakes last well into the morning. In off minutes, the vitelloni caper among the gravestones. “It’s Boot Hill, son,” Kenny Wood squalls in the distance, “the last roundup, motherfuckers.”

Jeff, who’s by now as hooked on dominoes as Bogdanovich’s secretary, starts up a game a few paces away from Larry McMurtry’s family burial plot. The markers for McMurtry’s paternal grandparents read:

Louisa F William J.

and

1859–1946 1858–1940

The sight of the stones sets up an aching urge in me to be away from the place; I’ve been to too many of these country boneyards for real, listening to shiny-suited shamans with faces like sprung mousetraps gibber piously over old men and women who were, somehow, in their lifetimes, a little better than they ought to have been anyway, given the time and place.

Over by the wind machine, Bill Thurman is sounding off to Bob Glenn about how loaded he’d gotten the night before: “I was so pissed outa mah mind, boy, I couldn’t have drove mah dick in a can of lard. You orta been there.” Glenn surveys the empty horizon and spits: “Everybody from here to the damn Atlantic Ocean is three drinks and two fucks behind, you ask me.” Nearby, Clu Gulager is chatting up a pretty young hot dog from Anson: “You got a boyfriend up there, do you? What’s he think about you comin’ down here to make a moom pitcher? Wahl, wahl, wahl….”

A grizzled old extra in a string tie and Mexican-tooled boots squints disapprovingly at Tim Bottoms, who’s lying face down on a grassy slope beyond the last row of gravestones. “Wouldn’t know a gol-danged rattler if one taken a gal-danged bite out of him,” he sneers, pouring together the makings out of a Prince Albert can.

Downwind from the action, Jody strums quietly on a guitar. “Oh, I had a friend named Ramblin’ Bob,” he sings, then looks up and notices Bare Doyle, who plays a Baptist preacher’s son in the film. “Yore daddy shore dresses you tacky, boy,” he cackles. Unlucky at dominoes, Jeff sprawls out in the grass to drowse in the sun, his head cushioned on a pile of jackets. John Hellerman stumbles through the maze of film equipment strewn about on the ground, looking viscerally shaken by the barrenness of the land. “Texas is almost all depleted now,” Gulager tells him with a brooding scowl. “It’s 20 million square acres of fucked-up land, that’s it.”

After a while, when the cameras move elsewhere, I go look into the open grave wherein Ben Johnson—“Sam the Lion”—is supposed to be laid. The brand name on the casket-lowering device says FRIGID, and you’d better believe it, little pardners.

Everything about him is gigantic, this sixty-odd-year-old cowboy spook who braces me later that day outside the Spur—his immense hands dangling out of the kind of gangrene-colored Western tent-suit you can buy at Leddy Bros. in Fort Worth for around $400, his watermelon-sized skull bulging out of a spotless XXXXX Stetson beaver, even his blinding-white dentures glistening like a wholesaler’s display of cue balls out of a massive, rutted face that looks to have been marinated a winter or two in creosote and brine. He’s M. B. Garrett, as it turns out, from over in Prairie Grove—lived over there all his life, he says, has a little spread over there, in fact, just a few thousand acres, the place mostly takes care of itself these days, even though his boys have up and moved off to Dallas on him, so he’s chancing a one-day flyer in this crackerjack movie-extra game…—and say, look-a-here, do I mind some company over to the commissary for a leetle snack to eat? He’s heard the food over there is right tolerable today—steak, fresh greens, and biscuits—and, anyway, he’s curious about that little spiral notebook he’s noticed me scratching in all day.

Sure, be glad to have you, I say, shaking hands and moving off in the direction of the dining hall. But he detains me with a polite thumb and forefinger encircling my upper arm: “You don’t wanna walk over there, do you?” he asks anxiously. Why not? I shrug, it’s only a block or two—“Because my whiskey is under the seat in the truck,” he explains patiently, pointing to a dusty Ford pickup at the curb with a bumper sticker that reads: When guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns. Oh, I hear myself saying in a faraway voice.

This M. B. Garrett from over there in Prairie Grove turns out to be a self-cooled, rapid-firing, semi-automatic sagebrush yenta as he fishes a fifth-sized bottle in a brown paper bag from the accumulated detritus on the floorboard and guides the Ford at a creep across the square and into a mire of unpaved streets. Between bowel-stinging jolts from the bottle, which we pass gingerly back and forth like the hot stuff it is, he geysers out jocular gossip about the McMurtry clan, past and present, and says as we pass a local doctor’s pretty daughter: “Married twicet, divorced twicet. She’s been warmed-over for the next feller in line twicet-over, you might say.” He brakes to peer up a side road: “Might as well take the long way around. Give us another excuse to take a leetle snort.”

When we pull up at the dining hall several excuses later, Garrett puts on a long, sorrowing face and announces that he has a “confession” to make—“That toddy you been drankin’? Well, I’m obliged to tell ye it was half vodka and half Old Crow. I didn’t have no full dram of neither when I set out this mornin’, so I just taken and mixed ’em both up in the same bottle. Hah! Bet you never knowed it, am I right? That’s a good one on ye, ain’t it?” Garrett is still guffawing when we unload our lunch trays at a table where the location manager is poking apprehensively at his greens and reading a paperback copy of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

At the sight of the book’s title, Garrett imitates a little boy reciting a nursery rhyme for the PTA:

Wire, briar, limber-lock,

Three geese in a flock.

One flew east, one flew west,

One flew over the cuckoo’s nest…

“And shit a big gob,” he concludes in the little-boy falsetto, clicking his dentures to underscore his wickedness. Wolfing his food so he can get home and hay his stock before nightfall, Garrett slyly intimates that he himself has been interested in books for quite a spell now—for years, in fact. Yesser, why, he himself even buys a book now and again from what they call—what is it now?—aunty-quarian book dealers? Up there in New Yowrk and so on? Yesser, he himself, in matter of active fact, concentrates mainly on collecting rare editions of Texans. In matter of goddamn active fact, he owns one of the only complete collections of J. Frank Dobie in existence, and he reckons it’s worth a right smart of money—at least, that’s what those aunty-quarian whoosits up there in New Yowrk claim, if you can take such people at their word, sight unseen and all. Sight unseen, because he doesn’t get up to New Yowrk much anymore—his wife’s health ain’t all that it might be now, and she never did cotton much to missing Sunday services over there in Prairie Grove, anyhow. But if my friend there and me are interested in such truck—J. Frank Dobie and all such as that—and we ever happen to get over there to Prairie Grove, why, you know, just look him up, everybody knows where his place is at…

After the old man takes his leave, the location manager shakes his head in wonderment. “What in the name of God’s body,” he whispers, “was that?” Somebody who’s been trying to kill me all my life, I tell him as a joke. Only, judging from the way he cranes around to peer at me, it doesn’t quite come out that way.

Getting dressed to go back to Wichita Falls that night, Loyd Catlett calls out to Jeff Bridges with studied nonchalance: “Whyn’t you’n me run over by the high school tonight, Jeff—you know, fool around some?” Jeff explains that he isn’t feeling well; when he gets back to the hotel, he says, he’s going to bed and stay there for the evening. “Aw, sheeit,” Loyd grumbles, crestfallen.

My part in the picture is finished by now—Academy all the way, William Medford Lewis—so I’m essentially hanging out the next day when the shooting commences with a brief picnic sequence in Hamilton Park—the Beverly Hills of Wichita Falls, kind of—then shifts to the Cactus Motel on Old Iowa Park Road for the exteriors of a tryst scene involving Cybill and Tim.

Every hole-in-the-road town in the short-grass country has its version of the Cactus, a sagging row of plaster-and-lath cabins beneath an eternally winking “Vacancy” sign. Next door is a franchise tamale joint, and beyond that lies a solid mile of truck stop cafes, liquor stores, used car lots, filling stations that solicit all known varieties of credit cards, and about a hundred or so of the baddest beer bars in the Western world.

As the troupe disgorges from the bus, the sun beats down, fleets of semi trucks roar by on the highway, and a gaggle of townspeople gather to gawk and shyly shake hands with the actors they recognize. “It’s so inneresting,” a rabbit-toothed woman in pedal pushers exclaims. “Look,” somebody hisses softly, pointing at Jeff, who’s hunkering down alongside Loyd on a plot of dead grass beside the generator truck, “there’s Beau Bridges.” “Who?” “Lloyd Bridges’ kid.” “Oh.”

While the propmen are dressing the scene, Bogdanovich lounges against the hood of a car, doing a fair-to-middling imitation of Peter Lorre. As all good secretaries do on such occasions, Mae Woods registers 100 on the laugh-meter. Cybill sits off to one side, intently squinting into the pica-choked pages of Crime and Punishment. Nearby, one of the grips is trying to shmarm over a tushy piece of the local Freez-Kreem talent: “What we’re doing, see, is making a lap-style horror flick—It Came to Eat the Freeways, you dig. Stars eight thousand Datsuns and a beat-up old VW bus. There’re still a few bit parts open, though. Sa-ay, do you think you could play a topless sheriff at a Mississippi kill-in? I’ll speak to the director about it myself. Like, gimme your phone number and I’ll get on the horn to you first thing tonight…”

Slack-jawed but firm-butted, the girl dutifully pokes through her bag for something to write on. There isn’t even the faintest quiver of comprehension in her face.

Meanwhile, on their tiny plot of dead grass, Jeff and Loyd are embarked on an extraordinary exchange of their own. Jeff is saying in a casual, offhand way that he knows Loyd doesn’t do much reading, but anyway, he’s got this spare copy of a book called Steppenwolf in his room at the hotel, and he wants to lay it on him … you know, whatever … just in case Loyd ever gets the urge to read something in an off minute.

“Steppenwolf. Is that that rock group?” Loyd asks. “Shit, boy, Ah lahk rock—it puts fuel in mah airplane.”

“You might even find out you don’t want to be a movie star … You might find you want to be something altogether different, you know? The thing everybody has got to learn is—channel that energy.”

No, Jeff explains—still ever so offhandedly, casually—the rock group in all likelihood took its name from the book, which is about—well, about this dude named Steppenwolf, Loyd’ll just have to read about it for himself to understand….But if there’s an overall message to the book … you know … well, maybe it’s something like—Keep movin’….Or, whatever….It’s only a book after all, but still and all, Loyd might get something out of it that might, you know … change his way of thinking, his values, stuff like that—

“Ah ain’t good at books—Ah don’t have to tell you that—but Ah lahk that message, whatever you call it,” Loyd says, worrying at his teeth with a stem of grass. “Keep movin’—shit, that’s mah meat, awright. Listen, Jeff—you reckon Ah’d make a fair Western star? Ah’m savin’ mah money so’s Ah can go out to California when this outfit’s done shootin’ here, but what happens then? How do Ah go about gettin’ in the union, do you know? The Screen Actors Guild? Mr. Surtees said he wants to do some stills of me if Ah ever make it out to Hollywood. And John Hellerman—you know, he’s an awful fahn little man—he gimme a mixed drank last night up in his room at the ho-tel and tole me Ah could bunk at his place when Ah git out there. Well, shit fahr and save matches, maybe ever’thang’s gonna turn out awright, you thank so?”

Jeff, no longer offhand or casual, hunches his shoulders forward intensely and gestures in an agitated circle: “I don’t know, Loyd. Nobody knows anything for sure, so nobody can tell you anything for sure. If some dude says he can, then he’s bullshitting you. That’s why it’s important to keep moving—keep tryin’ to understand yourself better in the world, the real world of true recognitions.

“OK, so Surtees and Hellerman say they’ll try to help you. Well, I’ll try, too—I’ll give you my L.A. address, to start with. But I don’t want you to get your hopes pumped up too high, because you might not make it. Probably won’t, in fact. Hell, you might even find out you don’t want to be a movie star, blah-blah-blah. Follow me? You might find you want to be something altogether different, you know? The thing everybody has got to learn is—channel that energy. I mean, like in your case, don’t fight with your fists anymore, all that jiveass shit you’ve told me about. Fuck, or eat, or climb a mountain, or do something useful instead.”

Unused to such talk, Loyd passes a troubled hand across his face, then blurts impassionedly: “Gawddamn it to hell, Jeff, it’s hard for me to keep thoughts lahk that in mah head, but Ah’ll try, and you got mah word of it, buddeh! Hell, Ah wanna know about all that stuff you mean—values and thankin’ and all that shit. You just way out ahead a me, is all, and it’s hard as hell to catch up. Ah guess just bein’ in this movie, gettin’ to know a guy like you and all—that’s changin’ mah lahf, ain’t it?….

“Ah was thankin’ the other night at the house—you know, just settin’ around thankin’, lahk a guy’ll do—and all of a sudden, Ah was on the subject of God. Jesus Christ, Ah says to mahself, what’s goin’ on here? Ah never did figger it all out to suit me, but anyways, what Ah was thankin’ was you limit yourself to God, but He don’t limit Hisself to you, does He? Ah mean God can be whatever he takes a notion to be—a tree or a rock or whatever the fuck….But a guy cain’t be nothin’ but a human man, see what Ah’m gittin’ at? And you know what? Alla that made me feel-lonesome, somehow. Ah don’t know how to explain it, but Ah guess you cain’t hep but feel lonesome sometimes, can ye?”

Later, leaving to go back to the hotel, I draw Loyd to one side and thank him for being in my movie. He looks surprised for a minute, then gives me a gentle poke on the arm. “You’re kiddin’ me, ain’t ye, doctor,” he says pleasantly.

The next afternoon, under a lowering sky, Cybill puts aside her books and sets out with a male companion for a meandering stroll to the Wichita Cattle Company auction barn, located about a mile from the hotel across the kind of middle-class black ghetto that would have been unthinkable anywhere in Texas a decade ago. Along the way, she languidly waves at children playing in the scrupulously clipped yards and ticks off the key events of her vita brevis with the heatless detachment of a NASA lifer selecting trinkets for inclusion in a time capsule:

A wealthy “philistine” upbringing in Memphis … growing up absurd, all that … winning a “Model of the Year” contest … moving to Barrow Street in the Village … meeting an “older man,” a Manhattan restaurateur, who introduced her to the Truly Important Things—music, the theater, abstract expressionism, the European literary heavies….“I never learned how to make friends,” she reflects moodily, peering down into the dung-pungent shadows of the deserted auction arena. “But … I learned early how to fill needs.”

Prowling around the barn’s maze of tunnels and chutes, she wanders out on a raised plank walkway overlooking pens of cattle being fattened for sale. “What do cows do mostly?” she asks abruptly. The usual things animals do, she is told. “Eat, you mean? Sleep? Make love? I think I might like to be a cow.”

On the way back to the Ramada, she chews on a piece of straw and confides that the illusionary business of making a movie is troubling her. “It’s like living in a hall of mirrors,” she says, smiling a fragile, very private smile. “It’s like being dumb but reading Kafka, anyway.”

The Picture Show cast begins to scatter in all directions like M. B. Garrett’s limber-lock geese; by now, Bob Glenn has returned to the sci-fi mother ship in Dallas, Cloris Leachman and Clu Gulager have departed on separate flights back to L.A., and I’m scheduled on a San Francisco flight out early the next morning. While I’m packing, it occurs to me that I’ve missed seeing Pam Keller’s rushes. Debating whether or not to call her, anyway, and try to bluff it through—Terrific, Pam baby. Academy all the way—I head down to the hotel restaurant and join Jody Heathcock and Eileen Brennan for coffee.

Eileen, who plays a salty-tongued barmaid in the film, has just boosted a pair of 89¢ sewing scissors from a five-and-dime store, and she crows about her petty thievery elatedly as she knits and purls on something gruesome and fuzzy spilling out of her lap. Jody is slyly jiving the waitresses, Carole and Winnie, as he’s done with their sisters-in-aprons a thousand times before, playing one-night stands from Yazoo City to Weed. The two girls are loving it; they can’t, in fact, get enough of that cool, adenoidal a-ha, because this guy is Jody Heathcock, after all, who used to be a famous big shot with Bob Wills, that famous old-timey bandleader their folks used to rave about after drunken Saturday night stomps at the M-B Corral. Besides, Jody knows—is friends with plays golf with—all the famous big shots in the world—Faron Young, Roy Acuff, Dean Martin, Marvin Rainwater, Sonny James, Frank Sinatra, Stringbean, Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Glen Campbell, Jim Nabors, Engelbert Humperdink, Cowboy Copas, Johnny Cash—the list is endless….Hot damn!

Winnie, arms akimbo on the counter, initiates the flirty ritual as Carole serves Jody an open-faced sandwich: “Well, hah yew today, Mr. Heachacallit?”

“Aw, I’m sick in the bed, honey. Say, look-a-here, when’re you’n me gain’ down the road for a leetle piece, you sweet thang?”

“Don’t you take me for granite, Jody,” she sniffs. “Besides, you’ll have to ast my ol’ man about that.”

Jody winks at her and turns to Carole: “What kinda sangwich is this you brang me, anyways, dear heart?”

“Freench dip. What you awdered, ain’t it?”

“Well, bless mah heart, Ah must have. Listen, set down here beside me and Freench mah dip agin, darlin’.”

Carole cracks her gum and pretends not to know what he means: “Naw. I’ve awready eat.”

“Anybody Ah know?”

“Oh, you. You’re the filthiest-mouthed thang I’ve ever saw!”

“Me? Why, you’re shore one to talk. Least Ah don’t let mah meat loaf, lahk you do. What’s a sorry, mattress-assed ol’ gal lahk you doin’ in a nice place lahk this, anyways?”

“Hmnph—you’re gonna be the sorry one, you ol’ letch. You’ll never know what sweet lovin’ you missed, neither.”

Jody looks her up and down for a minute, from bouffant topknot to rubber soles: “Bah damn, Ah bet if you ever got to sunfishin’, you’d break a man’s back. What time you git off tonight? I’ll be Don Ameche in a taxi, honey—all you got to do is bend over and I’ll drive you home.”

“Well… I don’t know about that. I’m not even sure I lahk you anymore.”

Jody drowns a final hunk of bread in his gravy boat, then rises and hitches up his trousers: “Well, that’s purely up to you, dumplin’. ’Cause Ah’m likable.”

Late that night, there’s a small birthday gathering for me in Jeff’s room; from Mae Woods or somebody, word has gotten around that my ravaged face is a year older. Cybill Shepherd shows up, and so do Eileen Brennan and Jody, Loyd, Tim Bottoms, and the location manager. Soon, some imported Mexican hors d’oeuvres are making the rounds, and Jagger is bleating “Sympathy for the Devil” on a tinny cassette machine. Jody, sucking contentedly on a pipeful of something pungently contraband-smelling, buttonholes me to ask, “Say, look-a-here Grober, you got anythang sharp and shiny to carry in yore pocket?” As a present, he gives me his bone-handle whittling knife. As my last sober act of the evening, I hand him back a penny, because when a man gives you a knife in the short-grass country, you can’t accept it without giving a gift in return for fear of severing your friendship.

Loyd, his hat shoved back at an angle on his dark hair, is sitting in the middle of the floor, taking the first toke of his life in the real world of true recognitions. He sputters and coughs and grins lopsidedly: “Sheeit, that stuff makes ye feel boneless, don’t it?” Before the Stones have given way to Elton John, he’s sprawled out full-length, asleep. The music and the Mexican imports burn on. Sure, you can go home again, I hear myself telling someone much later, if you’re making a movie.

This story is collected in Splendor in the Short Grass. Head on over the Criterion Collection for more on The Last Picture Show.