A few summers ago, Toni Morrison looked out at the Hudson River from the little pier of her house in Rockland County and discovered that she was feeling dizzy. She had, at the urging of her editor at Knopf, finally quit her job at Random House to concentrate all her energies on writing fiction. And now, lulled by the sight of the water swelling by, she realized that a great burden had been lifted from her. Still, Morrison knows, what weighs you down also anchors you. She was not only lightheaded with relief, she was giddy with fright.

A child of the Great Depression, she had worked since the age of twelve and, in adulthood, had toiled over other people’s manuscripts, taught college classes as well, raised two sons, and stolen time from the night to write fiction. Absent an annuity, a steady wage is as close to security as a single parent can get. Moreover, Morrison is a proud and rather distrustful woman who hates to be, in her word, “beholden.” That condition includes accepting publisher’s advances. Each of her four fine novels of the American black experience, from The Bluest Eye in 1970 to the best-selling Song of Solomon and Tar Baby of recent years, was written without a contract and completed before it was sold.

As Morrison saw it, with her nice sense of irony, “The games that I preferred were always ones where I was the only player.” She liked the idea of competing only with herself; she was certain that she could be more critical and more perceptive about her work than any professional reader, even Robert Gottlieb, a former Knopf editor who published her until he moved recently to The New Yorker. Besides, “to have had a contract before I had done it would have made it a homework assignment.” Having considered and finally vanquished all these doubts, Morrison wrote a formal proposal, took an advance, set to work, and turned out an amazing book, the best of her career.

Beloved, set in post-Civil War Ohio, is Morrison’s first period fiction. Although she insists it is not a novel about living in slavery, it is, among other things, a novel about living in slavery and about remembering it and, finally, through mythic and tribal exorcism, about learning to survive its cruelest wounds. In great part, the book is the story of Sethe, the runaway Kentucky slave woman who cheated her master of his ownership the only way she knew—by destroying his property. The setting is a house first haunted by the “spiteful” spirit of a murdered baby and then possessed by its adult incarnation.

“I wrote like someone with a dirty habit. Secretly, compulsively, slyly.”

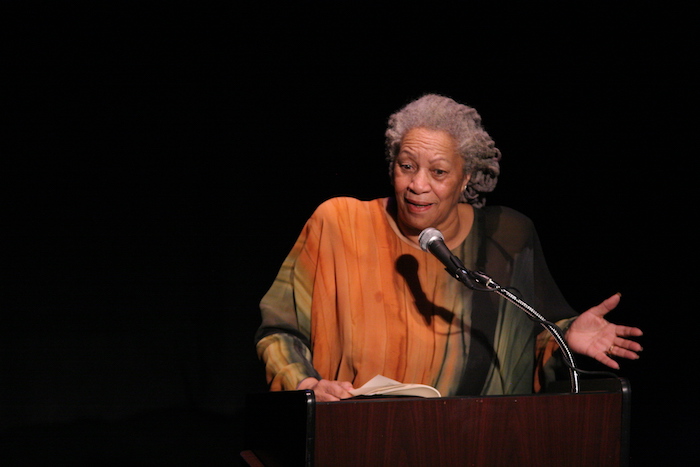

A little while before publication, Morrison, fifty-six, a robust, joyous woman with skin the color of creamy caramel and dark, smart, animated eyes, traveled down from Spring Valley, New York, to Knopf’s offices in Manhattan to talk about her book, an undertaking that had surprised her in several ways. After Tar Baby in 1981, she thought her novel-writing days were probably over. “I would not write another novel to either make a living or because I was able to. If it was not an overwhelming compulsion or I didn’t feel absolutely driven by the ideas that I wanted to explore, I wouldn’t do it. And I was content not to ever be driven that way again.”

So Morrison turned to theater, writing the book and songs for a musical she called New Orleans. Centered on the great flowering of jazz before 1920, it had a workshop production in New York in 1983. By that time, an old memory was pursuing her: At Random House ten years earlier, she had edited The Black Book, a scrapbook of bits and pieces about significant moments in the lives of America’s black people. One item had been an 1855 newspaper account of a runaway Kentucky slave who, about to be recaptured in Ohio, had killed her child rather than return it to a future of servitude.

Never forgotten, the story suddenly seized her imagination, and she found herself thinking about a work that would use the episode to explore the period and the people. Gottlieb liked the idea and at last persuaded her it was time to become a fulltime novelist. This new state, she discovered with delight, allowed her the luxury of an occasional day of “being fallow” instead of rushing around tending to incessant professional and domestic chores.

Midway into the book, she blocked and set the work aside to try her hand at a play for the Writers Institute at the State University in Albany, where she teaches one course a semester as Albert Schweitzer professor of humanities. Her Albany colleagues had asked for something special to mark the creation of Martin Luther King’s birthday as a public holiday. Morrison’s response was Dreaming Emmett, a play about a cause célèbre of the ’50s—the murder of Emmett Till, a Chicago teen-ager who had spoken to a white woman in a store in Mississippi. Eight months later, the play had been done, and Morrison, worn down by the demands of theater, was eager to go back to her novel.

Last fall, she brought Gottlieb what she thought was the first third of a very long book and reported apologetically: “It’s not going very fast.” Gottlieb’s response after reading it was, “Well, Toni, you have a book here.”

She had planned a novel that would carry the descendants of her Kentucky-Ohio people of 1873 into the twentieth century; the middle section would concentrate on one year of the great explosion of the arts in the Harlem of the ’20s and the last would deal with our own time. Now, to her surprise, Morrison has the first volume of what is to be a trilogy.

In a biographical note she wrote for an earlier work, Morrison reported that she first started to set stories down on paper years earlier, when she was teaching at Howard University and her marriage to the father of her two children was breaking up: “I wrote like someone with a dirty habit. Secretly, compulsively, slyly.” Even when she went public it was hard to tell people that, as she put It, writing is central to her life. For a long time, she was “an editor who wrote, a teacher who wrote, a mother who wrote.” It’s a pleasure to report that after five books Toni Morrison finally has given herself permission to acknowledge flat out that she is a writer who writes.

[Photo Credit: Angela Radulescu]