San Francisco

It is probable that Frederick Exley was the best-known unknown novelist working in America during the seventies. Ever since the publication in the late sixties of A Fan’s Notes he has symbolized the enigmatic position of the serious writer in this country. That book and the publication of the second volume in an autobiographical trilogy, Pages from a Cold Island, did little more than further Exley’s history of living on the economic edge. People in America don’t want to read about poverty and alcoholism and suicide and divorce, which is what Exley writes about. They want to read Jackie Susann paperbacks about Hollywood and cocaine and boys doing erotic things with other boys. The best sellers these days are not written by writers. They are written by shrinks and jocks and sex doctors and escape artists and gangsters and former White House people and other actors.

This is a hell of a time for writers. Billy Faulkner wouldn’t be able to buy the groceries these days unless he found a way for the postmistress in Oxford, Mississippi, to get raped at high noon down at the railroad depot. You have to have sex or white collar crime or an international conspiracy or UFOs or sharks to make it now. John Steinbeck published The Grapes of Wrath forty years ago. It was all about the rich versus the hungry. That, incidentally, is the test of a great novel: Can you sum it up in one sentence, or, better yet, one phrase? They called Steinbeck a communist when the novel came out in 1939 and it was 1962 when he finally won the Nobel Prize in spite of the flak. Good timing, there, John. Today nobody wants to read that crap. Reality, thy name is mud.

Fred Exley is pushing fifty years of age now. His life, once a disaster, is coming back together. He was born and reared in Watertown, New York, where his father was the all-time local football hero. That is what A Fan’s Notes is all about: how the son of the small-time biggie manages not to cope. Ex went through divorce and whiskey and impotence and insanity—he doesn’t bother to change his own name in the “novel”—but now he is making it. He paid his dues. Now he turns out to be something of a pussycat, living four blocks away from his mother in an apartment in Alexandria Bay, New York, where he cooks and cleans and washes for himself and drops into a neighborhood bar to drink with the same guys he once got into trouble with as a kid.

“You Southerners like to talk about roots, like you invented it,” he was saying the other day, “but I got news for y’all. Everybody wants to go back home.”

His books are classics read mainly by critics and other writers and people eager to honor distinguished writers. The last he heard, A Fan’s Notes had sold fewer than eighty-five hundred copies in hardcover (the author sees approximately one dollar per book on a hardcover) and was going into its sixth futile paperback attempt. Pages from a Cold Island, which came out in the late seventies, hasn’t done a bit better. The final autobiographical work of the trilogy—this Exley journey through America—is called Last Notes from Home, and there is little hope that it will do anything at the box office. “What you’ve got to do,” I was telling him yesterday, “is take up with somebody who can handle all of that money from your estate. Writers like you get rich fifty years after they die.”

Ex just left. He spent two nights sleeping on our sofa—all right, one night, taking out for the evening he spent alley-catting—en route to Hawaii. He planned to spend six months or so at Lanai City—on a plantation, with somebody he went to kindergarten with—and to try to finish the third novel. Then he would go back home to upstate New York to do whatever was necessary for survival. A movie was made of A Fan’s Notes—so bad that it never got below Canada—and there are always pieces to be written for the magazines.

Exley, having lived through personal disasters before, has more or less made a separate peace with the world. He is a novelist in the purest sense. He suffers and takes notes and lives to get even with the bastards. He is good and he knows it. He doesn’t cotton to the literati hanging out every night at Elaine’s in Manhattan and the Lion’s Head in Greenwich Village and those pubs on Long Island like Bobby Vann’s. He prefers to live near his mother and the guys he grew up with, up there in an isolated part of the country where it gets deep in snow about this time of year (“Going to Hawaii is a cop-out, like running from a fight, but it’s my cop-out”), and to continue writing about what he has seen and lived through.

So. Ex and I had some fun together. My wife and I threw a party on his first night in town—all writers and editors, although the only guest who had read A Fan’s Notes was a slump-shouldered socialist who once knew Bob Dylan in Minnesota—and Ex lay about the next night because of what transpired earlier that day. I was then the hot new columnist for the San Francisco Examiner and had finally been invited to one of the semifamous Round Table Luncheon gatherings thrown by an upwardly mobile divorcee named—for the present—Pat Montandon. Pat and her rich husband of the moment invite a dozen or so “famous” and “exciting” people, known as “personalities,” to their elegant penthouse atop Nob Hill. Everybody sits around sipping cocktails and being served lunch by a German husband-and-wife team and then discusses important issues like Transcendental Meditation. The luncheons become Radical Chic pretty quickly. Ex and I, at any rate, warmed up at my place with bloody marys and then took a cab.

“You want to frisk me?” Ex said to the guard at the elevator. “All I got is a flask.” We ascended to the penthouse, had some martinis, and then everybody sat around the famous round table. Pat Montandon, as is the custom, went counterclockwise around the table.

Each person was introduced and asked to talk about what he or she was “involved with.” There was Jessica Mitford and the founder of the National Organization of Women and an effeminate liberal clergyman and a token black and I, the displaced Southern of a truck driver, and many others. Ex, this crazed novelist, was ordering more martinis and was wondering how far he would fall if he took a leap through the plate-glass window onto Jones Street.

“Frederick,” Pat Montandon said when it came his turn, “would you tell us about yourself and what you are working on?” There was terror in Exley’s face as he wobbled to his feet, drink in hand, and addressed the assembly. He whispered to the German Hausfrau to sweeten his drink. There was a wheeze and a long pause. “My name,” he told them, “is Fred Ex. I am an alcoholic.” Then he sat down, and Pat Montandon issued orders to serve lunch immediately.

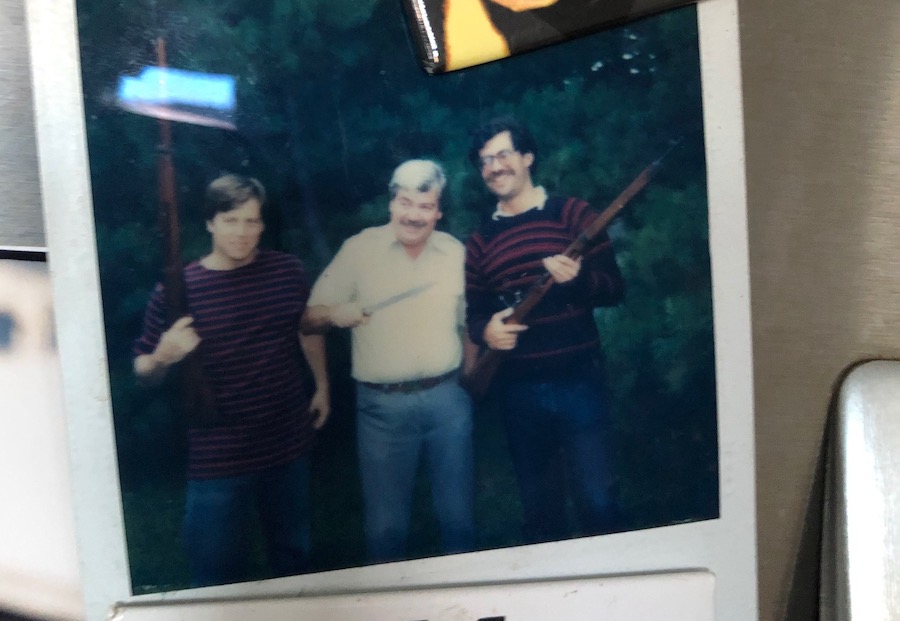

[Photo of Fred Schruers, Frederick Exley, and David Hirshey, courtesy of Hirshey]