Woefully, I must report that unlike Captain Spaulding, I did not leave drunk and early for Africa. Not that I didn’t try.

The problem was the cost of the package tour for the press, which began at $1,800 and then was reduced to a mere $1,400 pittance. Such a sum was beyond my paper’s comprehension, since they consider Hoboken an overseas assignment.

For a while all was not lost. Indeed, it was touch and go. A couple of my fringe connections (actually two good friends, but the former phrase winks at Blinky Palermo intrigue) lobbied with Video Techniques to send me as a guest. In their eloquence, they argued that I had paid my dues at Sunnyside, the Golden Gloves, and the Garden over the past eight years and my absence would be Africa’s loss. My presence was touted as symbolically essential as the frozen carcass of the Kilimanjaro leopard.

Whatever dubious impression this made on the promoters, it impressed the hell out of me. I began to feel like that notorious deadbeat, the Duke of Windsor. Could it be a party without me?

For two weeks before the original September 25 date of the fight I checked in daily by phone with Video Techniques to see how my stock was rising. At first, I had a “40 per cent chance” of attending; three days later, I crept toward “50,” and the following week (two days before departure) I “took off” to “80.” Any fair barometer would cite Merrill Lynch and me as the only bullish things in America.

But there was an additional problem—my inoculations. The series of shots ideally was to be taken over a period of three weeks, along with a steady intake of quinine pills to ward off malaria The press plane was to leave on a Sunday evening, and here it was Friday and all I had to ward off the dreads of the dark continent were my pre-grade school vaccinations, and they were so feeble they hadn’t fended off the wrath of my first grade teacher, Sister Pascuale. But in fairness to my vaccinations, it must be said that even though the good sister lacked the moves, she had Marciano-like devotion to her mayhem.

So with my china, Tommy Sugar, who serves as my unquestioning Cato for such enterprises, I set out in his car to condense three weeks’ preparation into an afternoon.

It was his contention that the quinine question could be settled peremptorily by warming up on Beefeater-and-tonic. It was a pleasant solution and one that would reduce any apprehension over the series of shots.

After some lusty preliminaries, we arrived at a passport photo shop, and pictures were taken for my visa. The finished product was spectacular. From the look of my eyes, I was sure the authorities would stamp my stateside residence as “Village of the Damned” and list my father as Walter Keane.

All that literary ego and competition down there waiting to be tested, and here for months I had been storing up a footlocker of my most precocious metaphors.

After some more infusions of quinine, we arrived at a posh (30 bucks for 30 seconds) East Side picador’s clinic for my shots. Our last stop was to fill out my visa, a tactical mistake, since by this time my penmanship could only be described as palsied Palmer. But all said and done, this miraculous windsprint coup was pulled off; and I experienced the same heady feeling the Lord must have felt when He brought it in with a day to spare.

Saturday my stock and my ego plummeted—I was informed I was to be a no-show. What a deflation! Only my head and my arm were still bloated. I couldn’t believe I had been hometowned by the philistines.

Oh, how dearly I wanted to go—for myriad reasons. Indeed, I had fantasized about the trip for months. And when the bad news about press censorship and government bullyboying began to emanate from Zaire, it made me more eager than ever. Perhaps if I wrote the most scathing copy on the continent, I would become a political prisoner, a cause célèbre! (l’ve always had a closet desire to have the Berrigans say a hip mass for me.)

Being what he is, Ali is a man who creates seesaw emotions in his chroniclers.

When the word that the press would be billeted together had come, my gray matter turned to gingerbread. Was it not possible the submerged Sgt. Croft in Mailer would surface, and he would run literary police calls every morning on the grounds (“All I want to see are assholes and elbows.”)? And perhaps George Plimpton would be moved to his last outpost as our syntactical surrogate and don Man-Tan to write the fight as seen through the eyes of an African?

All that literary ego and competition down there waiting to be tested, and here for months I had been storing up a footlocker of my most precocious metaphors, a veritable arsenal to be leveled on the Congo—chasing Hem’s prose style across the river and into the trees.

Also, of course, there was Ali. Being what he is, a man who creates seesaw emotions in his chroniclers, he must be clocked at first hand. Sportswriters shuck their judges’ robes when it comes to covering him. He has become so politicized it’s hard to find the athlete underneath. This sin is not peculiar to many of the old line writers, who can’t see him through their strangulated vision of what he “stands for.” It also applied to many of the new liberal breed, who zero in more on his counter-culture than his counter-punching.

To them, he is a great anti-war hero, which simply is not true. In their passion they forget Ali never had a carp against the war while he was safely failing his induction tests. In this, he was similar to many who adopted the dovish position when it became evident a solution was beyond reach. It should be remembered that Ali’s first line of defense against induction was that as a fighter his taxes would enable the government to “buy airplanes,” while as a dogface his earnings would be of popgun proportions.

On the other hand, many of the old school continually conjure phantoms of the past who would demolish him.

Both sides in their lifestyle heat seem to have shunned critical judgment of what Ali does—box. They are like drama critics who ignore the play and concentrate on the private peccadillos of the playwright and the actors. In short, Ali brings out the Rona Barrett in both sides.

On the side of the angels, Ali has single-handedly kept boxing alive.

This is odd, since the new breed was supposed to exorcise their elders’ cotton candy vision from the sports pages. Instead (there are notable exceptions), they have created gods in their own image and likeness (certainly Namath and Derek Sanderson are not culling that ink on one recent performance).

I have always fostered ambivalent feelings toward Ali. I’ve watched him sully his art with sadism against Ernie Terrell and Floyd Patterson and, on national TV, taunt Frazier for his dumbness, while an equally distasteful audience lapped it up. He cruelly mimicked Frazier’s slow speech, which bowed more to a barroom bigot’s version of a “dumb nigger” than it did to wit.

Also, Ali has been a pedestrian fighter of late. His matches with Joe Bugner, “Blue” Lewis, the two bouts with Ken Norton, and even his last bout with Frazier, were devoid of electricity. It can be said that when Louis did his “bum of the month” tour, he at least handled them as such.

But on the side of the angels, Ali has single-handedly kept boxing alive. When he was good, before a kangaroo decision by the boxing commission jobbed him, he was a joy. He wasn’t an experimental fighter for avant-garde reasons but a genius, like Picasso and Joyce, who broke the rules because he thoroughly understood them and they bored him.

The brain was for Foreman, the heart was for Ali. First, for what he means to boxing, and second and more important, because I believe his braggadocio style is a tonic to our times.

And he did for the boxing press conference what Jack Kennedy did for its political counterpart. With brilliant alchemy, he could transform scores of black opponents to white in the public mind (I believe he could make Eldridge Cleaver come off ofay). This time around, his pre-fight prattle was so ingenious Foreman had joined the former residents of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s cabin. It was the Nigger and the Narcissas all over again. Then, when Foreman (who would prove a willing accomplice through this whole affair) arrived in Africa with his German shepherd (among other things, George’s camp were not—students of history), he even lost his Tom status. Enter a colonial albino.

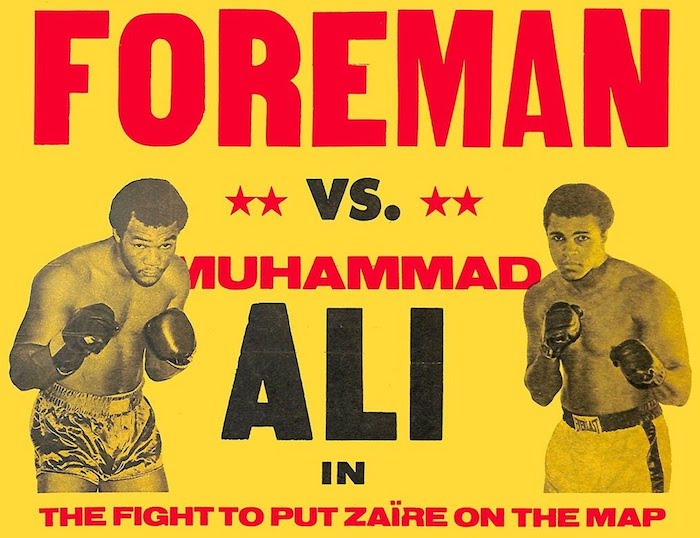

I thought Forman would win, because in his fights with Frazier and Norton he seemed to correct his glaring flaw of throwing punches that would make Ewell Blackwell look like an overhand pitcher. In both fights he punched relatively straight and with devastating power. He did to Frazier and Norton in four rounds what Ali couldn’t do in 54 rounds (Ali split a pair of 15-rounders with Frazier and a pair of 12-rounders with Norton). Though it was tempting to think that Ali had the perfect style to offset Foreman (Styles do win fights—journeyman Tiger Jones gave Sugar Ray Robinson fits.), it was difficult to conceive how Ali would keep Foreman off.

But though the brain was for Foreman, the heart was for Ali. First, for what he means to boxing, and second and more important, because I believe his braggadocio style is a tonic to our times. In this Age of Whine, where the ineffectual schlep has mounted the altar in our politics and arts (check the limp dick school of writing), Ali—like opera—has pretensions of grandeur.

I should have known when I took my seat at the closed circuit showing that Ali would be the winner and that my heady prognosis was faulty. Sitting two rows in front of me was Ralph Branca, whose presence bathed this old Giant fan with reflective warmth. The clue was there. The gods don’t dish out double dip treats in the same evening.

From the beginning it was clear that Ali had abandoned his float and sting strategy. Instead, he wove a web on the ropes. Foreman, smelling swoon, was all over Ali—with the challenger only occasionally coming out of his defense to pepper him. By the time the fourth round ended, Foreman’s corner should have gotten the message—Ali was into strategy, not fear. It was obvious Foreman was not going to knock out Ali in this fashion. Ali took all Foreman offered early (one forgot in his tout how amazingly well Ali takes a punch), and now Foreman was punching ineffectively. His punches reverted to his amateurish method, and their arcs became wider and wider, with Ali scoring between their brackets.

By the end of the fifth it was obvious to everyone but Foreman’s corner that Ali was content to let Foreman punch himself out. Just what the hell was wrong with that trio of smoothies—Dick Sadler, Archie Moore, and Sandy Saddler—in Foreman’s corner still baffles me. Why wasn’t there an abrupt change in strategy? Foreman’s punches are best at long range (as with all huge men), and here his corner had him strait jacketed on the ropes!

And even his rope fighting was dismal. He didn’t lean on Ali or try to abbreviate his punches but stood back from him with many pregnant pauses, winding up these roundhouse, temple-wrecking punches. If fighting is similar to war, Foreman would be a cinch to be an artillery man.

I would be curious to know the ratio of punches Foreman threw in those first five rounds to All’s output. Perhaps Sadler should have employed a pitching coach with a counter. But his corner seemed unaware of his output of energy and, as his corner not tempted to grab Foreman by the trunks and tell him to stand in mid-ring, forcing Ali to come out to him? Indeed, did they ever think of telling Foreman that he was the champ, and Ali had to take the crown from him?

Foreman fought like a desperate challenger who was dropping a clearcut decision to a champion in the last rounds in the champ’s hometown.

Of course, Foreman’s confusion could be attributed to the fact that he acted as Nixon did in his early presidency toward Eisenhower. He felt unworthy of the majesty and paid deference to Ali. Foreman fought like a desperate challenger who was dropping a clearcut decision to a champion in the last rounds in the champ’s hometown.

In the seventh and eighth Foreman had no punch left. He was pushing his right like an arthritic croupier. At the end of the eighth Ali exploded off the ropes with a combination, the last punch a twisting overhand right. It was a good combo, but what made Foreman remain prone was fatigue. For Ali, it was a yawner, an insult. One wouldn’t ask Rommel to master the tactics of ring-o-levio.

The post-fight Ludicrous Award goes to Floyd Patterson, who claimed he is the only man left who “could beat Clay.” That evening might be good for a giggle, if I could bear the Four Aces singing the national anthem.

The fight that has to be made is the rubber match between Ali and Frazier at the Garden, and at its conclusion both men should retire and open up the division to lesser lights. These two great gladiators have glutted us with grand combat, and they should bring the circle home where it began—at the Garden.

Before the fight in Zaire, Archie Moore said that Ali’s act “is now as thin as a Baltimore pimp’s patent leather shoes.” The old man should have stretched his sexual metaphor further. He didn’t take into consideration the hour of the fight—three in the morning.

When it comes down to a confrontation between a big rube kid and a sharpie at that desperate hour, history has it that the ponce hustles.