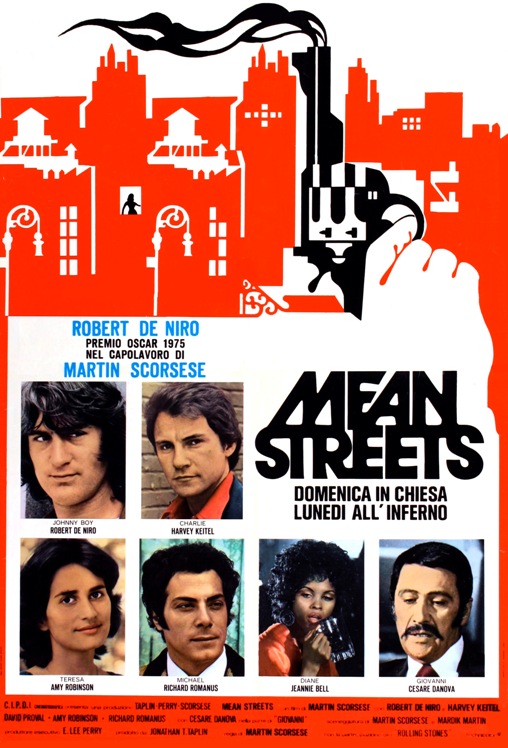

When I met George Malko a few years ago he told me about his friendship with Pauline Kael which began after he profiled her for Audience magazine in 1972. Kael was the one who invited George to a press screening of Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets the next fall before it was shown at the 1973 New York Film Festival. George saw the movie, contacted Scorsese’s publicist Marion Billings, and proposed a profile for Harper’s Magazine. Then he pitched it to the late Robert Kotlowitz, managing editor of Harper’s. Kotlowitz approved it and George went to Boston where he spent three days mainly with or close to Scorsese.

George wrote and submitted the piece, and it was rejected; there seemed to be some uncertainty about Scorsese’s future, how important he would prove to be. Journalism is always a calculated gamble and you can’t blame an editor for whiffing on occasion; in this case, of course, Scorsese went on to become one of the great directors of our time, Mean Streets his first masterpiece.—A.B.

Martin Scorsese is upset. His friend, Jay Cocks, film reviewer for Time magazine, has just called him here in Boston with bad news. “He said, ‘Marty, you should hear bad news from a friend.’” For a film director, particularly a relatively young one whose latest movie, Mean Streets, already looks like one of those successes that’s going to establish its maker as an important new and original voice, these can only be one kind of bad news: a destructive review.

Mean Streets inspires a particularly strong critical and audience reaction. A vision of life as it’s pursued by four young men as an elegy to Scorsese’s own youth, a time of grabass recklessness, messing around with broads (as opposed to girls), and terrifying violence which, as soon as it’s over, never seems as destructive as it looks, even when someone gets riddled with bullets; it is a reminiscence oozing exhilaration and doom.

Scorsese’s semi-autobiographical point of view is Charlie’s (Harvey Keitel), a young man who is almost enthusiastic about accepting the idea of his damnation and the reality around him; he secretly flirts with the possibility of some kind of temporal sainthood. The fires of hell, he thinks to himself as he periodically puts a finger or hand into a fire to see exactly how much pain he can stand, must also offer some kind of passion, there own eternal redemption. His loyalty to one of his friends, the almost suicidally irresponsible Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), is the cross Charlie bears. The money Johnny Boy owes the coolly ambitious Michael (Richard Romanus), is the plot-line on which Charlie hangs everything: he will make sure Johnny Boy meets his payment schedule, he will prevent Michael from leaning on Johnny Boy every time he blatantly ignores his “responsibilities.”

Aided and abetted by a musical score which cuts into scenes to make itself felt the way a character makes himself seen, Scorsese allows Charlie’s fragile intentions to collapse because, finally, this is a movie about a young man in terrible conflict with himself.

“What is it?” Marty’s girlfriend, Sandy Weintraub, asks. “What happened?”

Marty looks around for a moment, knowing his listeners are imagining for themselves the possible varieties of bad news he’s suddenly been hit with. “Jay said, ‘Highams interviewed Brian for tomorrow’s New York Times’”—with Jay Cocks, director Brian de Palma is one of Marty’s best friends—“‘and they did the interview in the apartment, and the apartment got a bad review.’ He said, ‘He called your apartment a dungeon.’” Marty starts to laugh, a full rich series of delighted bellows.

“What is real a saint?” he asks rhetorically. “Saints aren’t always crackpots…”

“Oh, my God, Scorsese, you’re kidding!” Sandy exclaims. She turns and says, “Brian’s living there, and all the windows are boarded up because they’re doing earthquake repairs.” She turns back to Marty. “They panned the apartment.”

Marty nods and begins to walk back and forth in the large drawing room of the hotel suite, which overlooks the Charles River. The day is overcast. A few sailboats are out on the river. Marty’s had two hours of sleep after arriving on the overnight flight from San Francisco where he spent two days during which Mean Streets was shown at the San Francisco Film Festival. He had spent a week in New York while the film was previewed, screened at the New York Film Festival, and then opened commercially to rave reviews; on a World Series/Pro Football Sunday it played to packed houses all day. Now it’s Boston: a Press luncheon, four interviews, and some people who just want to meet him.

Those who make the over-night coast-to-coast flights with any regularity have dubbed them the Red-Eyes, and Marty’s are scarlet. He rubs the exhaustion out of them and gets set for the long day: the juices are flowing and there’s challenge in the air. Small-statured, solidly-built, Scorsese is a thirty-year-old matador out of New York’s little Italy; with a strong nose and brow, and a prominent forehead, his profile is out of a Paolo Uccello.

“We ready?” he asks, looking around. He’s directed three shorts, supervised the editing on Woodstock, edited Medicine Ball Caravan, and directed three features, each demonstrating astonishing progress and a dazzling ability to seize material and make it his. Mean Streets has inserted his achievement of consequences: his next movie, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, is already in pre-production. He is the reason everyone’s gathered in this suite on the 27th floor of the Sheraton Towers.

When he asks, “We ready?” everyone is ready.

The Press luncheon is being held in the Adam’s Room of Boston’s august Ritz Hotel. Marty strides in to face the reviewers, journalists, and exhibitors who have come to meet him. He moves around the room shaking hands, his manner confident, at ease, considerate of any and every question or compliment.

Sandy Weintraub stands to one side, watching. She is in her early twenties, the daughter of Fred Weintraub, one-time owner-entrepreneur of New York’s Bitter End cafe an now a successful producer for Warner Brothers. A child of divorce and remarriages and the casual dislocations of our times, she is wise and self-assured in the way the very young that has survived. “Don’t give Marty a drink,” she says to Don Simpson, the personable young Warner Brothers press representative who flew out from Hollywood. “He can’t drink. He gets sick.”

Don’s reaction is quick. “He shouldn’t drink?” he asks warily, ready, preparing himself for A Problem.

“No,” Sandy says simply. “He just gets sick.”

Marty sits down at a table with five women and one man, and the lunch and interviews begin. His answers are informed and lively and candid and everyone visibly warms to him. As he talks, his physical persona changes, shifts slightly, and achieves its Latinate image. His hands come into play Sicilian-style, joined in prayer whenever he tries—begs—to make someone understand the point he’s trying to make. The journalists take turns dominating a moment, all save the red-faced doyenne of the Boston film corps, a woman who spent fifty-two years writing for The Globe and has now become sharply aware that she’s both “colorful” and “a character.” Looking at times like an angry onion, she asks all the traditional questions and jots down Marty’s sincere answers with the same attention she would give divine revelation.

“You don’t make up for your sins in Church; you do it at home, you do it in the streets. The rest is bullshit and you know it.”

“How does it feel to be a success?”

“I eat more oysters.”

A pause at the table; the women look at each other.

Marty watches them. He nods. “Really, I eat more oysters. And I put horseradish on things. More hot spices than I used to.”

The doyenne scribbles energetically. “Oh, Christ,” a pretty young woman at the table mutters to herself. She wants to know about The Movie. Is that Marty in the main character of Charlie, played by Harvey Keitel, and what about Johnny Boy? And the violence, which seems to rip into a scene the way some demented art fiend would slice into a benign cityscape from behind the canvas.

“Did your parents see the movie?” one of the women asks.

“Oh, sure. Sure,” Marty says.

“What did they think of it?”

“They liked it.” There is a pause as Marty looks around at everyone at the table, knowing after so many interviews that people wonder if he felt any hesitation about letting his mother see what he had wrought. “My mother said, ‘The language is a little too much.’” There’s a sigh of understanding from the reporter. “Both my parents felt a little upset about the language, and they felt I didn’t need the nude scene; could’ve done that scene without showing the girl. They liked the rest of it.” Someone starts to ask another question when Marty adds, “oh, a little too slow; my mother specifically pointed out the scene where Charlie gets drunk and the cameras on his face for a very long time. A little slow for her.” The reporters laugh at this pleasant incongruity: a director’s mom telling him his pacing is a trifle off.

“Did the guys you grew up with like it?”

“Oh, yeah. Not because it’s them, they’re highly disguised. They liked it because they remembered. The feeling of it was real, it’s exactly what we used to do, and it made everybody kind of homesick, because it’s all over. I mean, as far as we’re concerned it’s all over. But, there are other members of the neighborhood who got offended by it, because I guess they didn’t like the representation of the way they were, although they had nothing to do with the actual events in the picture. I clearly told these people, I told them, ‘This is a film about myself and Joey, and Robert, and Sally Gagá, and a few other guys, and that’s it.’”

“Do you see yourself as being Charlie?” someone asks.

“I do and I don’t,” Marty says. “My first picture, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Harvey played J.R., and that was sort of me, too.”

“Did you mean for Charlie to be a kind of Saint?” (“Charlie,” Pauline Kael wrote in a long appreciation of Mean Streets, “isn’t a relaxed sinner; he torments himself, like a fanatic seminarian.”)

Marty considers the questions. His face momentarily registers something, a temptation, possibly, to ring in a snappy answer, which would take care of the saint and sainthood once and for all. But Marty, who grew up on Elizabeth Street in New York, desperately wanted to be a priest when he was a child. “I felt I had a true vocation,” he admitted to one interviewer. If he’s made any kind of peace with his determination to be agnostic, zinging The Church is out. “What is real a saint?” he asks rhetorically. “Saints aren’t always crackpots…”

Everyone writes this down.

Someone asks what he’d like to see while he’s in Boston. Marty says it’s his first visit, but he would like to see something, maybe those eerie neighborhoods celebrated in the unsettling stories of H.P. Lovecraft.

“See Beacon Hill,” somebody observes half-cynically.

“What’s Beacon Hill?” Marty asks.

“Beacon Hill is a goddam interesting place,” the doyenne growls. “I live there. I know.”

The pretty young woman turns away, palpable nausea in her expression.

“Well,” the doyenne says some moments later and gets up. “I’ve got my lead.” She congratulates Marty again on his movie. He stands up to say goodbye. Some of the others rise and leave, too. All congratulate him.

Driving over to an interview on a radio station, Carl Fasick, the Boston publicist who has arranged everything for Marty’s visit, says, “I think it went well.”

“You think so?” Marty asks. From the moment it looked as if the movie was going to be both a critical and commercial hit, he has been totally accessible to help push it along. His short films and his first two features received lots of interesting reviews, but the clout to spring free and make the movies you want to make comes when the reviews make people go out and pay money to see your movie.

The radio interview goes smoothly and Marty enjoys the fact that the interviewer knows movies well enough to ask questions which link Marty’s personal heritage as a film buff to the realities of making a movie.

By 4:00 PM Marty is back in his hotel suite, doing yet another interview. He mentions that Andre Wajda’s film, Ashes & Diamonds, influenced Mean Streets. The interviewer doesn’t respond. He seems more interested in challenging Marty’s contention that even as a boy growing up on the lower East Side he was aware that certain movies had been made by certain directors.

“That’s true,” Marty insists. “We saw that John Wayne and John Ford, they went together, and we started to go see most of the Ford films because his name was on it. Howard Hawks, the same thing. Roger Corman.”

“Oh, well, yes,” the interviewer says, and cites directors he feels achieved their own uniqueness. This unreeling of the names of various directors and their movies seems designed to produce some sort of magical amalgam: it is the stuff of nostalgia and trivia. Marty listens and patiently responds with nods and small injections. Sandy sits at the card table, doing her nails, mildly bored. Out on the Charles River six sculls glad smoothly by, the tiny figures bending in unison.

“What are you going to make next?” the interviewer asks.

“It’s called Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” Marty says. “Ellen Burstyn’s in it. The title’s going to be changed, I hope.”

The interviewer nods and begins to discuss various ways directors take over movies. Marty agrees. “Alice is a perfect example,” he says. “If somebody else was making it, they could turn it into a Doris Day movie. But I’m directing, and it’s not going to be a Doris Day movie. It’s going to be mine.”

When the question of the irrational violence that explodes in Mean Streets comes up, Marty is eager to talk about it because critics and audiences have reacted visibly to the film’s craziness, the seemingly gratuitous brutality we seldom anticipate, even though his characters seem at times to radiate a kind of doom-expectation. It is an acceptance of an unpleasant, punishing inevitable rooted in both Catholicism and that old national hysteria which had New York’s Governor Rockefeller advising the citizenry to dig bomb shelters in their backyards. At Cathedral High School, a preparatory Seminary in New York, Marty remembers that at any hour of the day a Priest’s voice used to come booming over the school’s loudspeaker system: “Attention Please. Take Cover! Take Cover!” Marty repeats it now, imitating the voice, and laughs. “That’s what we grew up on,” he says and laughs again, incredulity in his voice because retelling it too coldly may suggest to his listener that was all normal.

“That was part of the fear thing,” Sandy says, looking up.

“Fear,” Marty acknowledges with a nod, “and guilt and craziness.”

But the interviewer is really on a different tack. He is remembering the violence of another New York. His New York. He is working hard to fuse his personal reminiscences of that city with Marty’s. It is as if successful fusion will make the stuff of his roots become what Marty’s have become: a Movie, the All-American Reality.

It is after five when he finally leaves. Marty gets up and stretches. “I’ll call your mother,” Sandy says, “and tell her we’re coming tomorrow.”

“Okay,” Marty says. “Who’s coming next?” he asks Don Simpson.

“Jon Landau,” Don says. Landau writes for Rolling Stone and gave a long and enthusiastic review. “His wife is coming, too. She was at the lunch before. Janet Maslin. She reviews movies for The Phoenix. And she writes for New Times.”

“What’s New Times?” Marty asks.

“A new magazine,” Don says. “She reviews music.”

“Great, great,” Marty says. He glances out of the window and sees the small sculls in the distance. “Hey, look.”

The Landaus arrive and are barely settled in when Sandy comes out of the bedroom, laughing. “Goldstein’s sent you a present for mentioning them,” she says. “A tie.”

Marty looks at her and his face glows. “Sy Goldstein,” he says with a mixture of genuine awe and mock respect, “haberdasher to The Underworld.” He laughs, but he is genuinely touched by the gesture. “I gave them a plug, you know,” he explains. He looks back at Sandy. “The sent me a tie. Monday, you know what I’m going to do, I’m going down and get one of those shirts, one of those white on white on white shirts.” He laughs again, savoring the irony and the flattery. “Goldstein’s.”

Feeling relaxed once more—the last interview was too much like an exam he was working hard to pass—Marty collapses on the couch. For the next hour he and Landau and Maslin talk about movies. Marty laughs a lot. He has a quick humor and now, tired, responds to the more ridiculous observations people make. His moods are infectious, and I feel both his exhilaration and exhaustion. Because Landau has come more to talk than to collect data for an interview, everyone is much more at ease.

“What was the name of that place Carl sad we should go to eat?” Marty asks Don.

“Jimmy’s,” Sandy says as Don nods.

“Come on with us,” Marty says to Jon and Janet. “I’ll change.”

When he comes back from the bedroom he has put on a clean white shirt and jacket. No tie. His black hair is combed down almost flat and as he slips into a double-breasted dark-blue overcoat he suddenly looks like the satirically confident button-man he portrayed in Mean Streets (Marty plays the hood who, in his own movie, shoots both Johnny Boy and Charlie, his surrogate-self). When he flexes his shoulders to settle the overcoat more firmly, the image is both reaffirmed and disturbed. There’s too much humor in the man. He knows there’s something incongruous about his looking like some ambitious pezzonovante. Exhausted and hungry, he’s ready to laugh at anything, including himself.

“You get the thing?” he asks Sandy as they step out the door.

Sandy nods and opens her purse to show him the small inhalator she always carries with her in case he might need it. As a child, Marty was asthmatic. It was the reason he began going to movies: he couldn’t play games with the other kids so his father took him to the movies whenever he could. As an adult he’s had several severe attacks, one almost fatal. I remember he’d told someone that the near-fatal attack was one of the things which finally convinced him to go into analysis. “The doctor thought I would die,” he’d said. “He felt I really wanted to, and my friends insisted that it was time I saw a psychiatrist. I resisted. I was afraid I’d lose my neuroses. I thought I needed them in my work; all the old fears superstitions, and what would I have if I lost them? It took me a whole to realize that you’d forget those feelings but can stop being plagued by them and become really free to use them.”

On the fast ride down Marty holds out his hand and Sandy give him the inhalator. He holds it for a moment, then takes a deep, comfortable breath and, as we touch the ground flood and the doors open, hands it back to her without using it.

In the taxi on the way to the restaurant, Marty’s exhaustion becomes more profound and we talk through and around him as he sits in the corner staring out at the dark streets. He seems uninvolved, barely there.

“I woke up this morning,” he says during a long silence, “and didn’t know if I was in the middle of the picture, about to start it or finished with it. I didn’t know where I was. I didn’t know what city I was in.”

The next day Marty sleeps late. When I get to the hotel around noon Sandy calls Carl Fasick, who recommends a restaurant for lunch. He plans to meet us there later and take Marty on a small tour of Boston.

“How do you feel?” I ask Marty when he appears.

“Okay,” he says and looks out of the windows. It is a clear, crisp day. “Great.”

At lunch he orders oysters. “Have to be consistent,” he says and laughs. “But it’s true, though. So is putting spices on things. Horseradish.”

“You’re just turning Jewish,” Sandy says.

“With help,” Marty says.

“You cook at home?” I ask him.

“Sometimes,” he says.

“Almost never,” Sandy says.”

“I do the dishes,” Marty says.

The oysters come and we start to eat. Then I say, “I was amazed when you said you’d shot Mean Streets in twenty seven days.”

Marty nods. “It’s true. Christ, I never want to do a picture with that kind of schedule again.”

“But the urgency comes through as energy,” I say. “Desperation, and kind of sheer, brute energy.”

“You think so?” asks, eyes alive, considering the possibilities, fascinated.

A taxi takes us to the Boston Common where we get out and walk around to see some of the historical landmarks. Carl Fasick supplies us with simple descriptions of the things we see as we walk. Marty is attentive, and seems to appreciate the chance to take time off to be a tourist. We drive to the Old North Church and then up to see Paul Revere’s house on Beacon Hill. When we come out the sun is still shining brightly, but a cold wind has come up and Carl suggest it might be a good time to pick up the rental car we’ll be driving to New York.

At the hotel, Marty goes up to the suite to get his bags organized while Sandy stops at the cigar counter and buys cigarettes. She sees a copy of New Times and buys it. Marty has everything ready for a bellboy to take down when she arrives at the suite, New Times open to a review of Mean Streets. All of the Boston papers have been very enthusiastic. Marty drops into a chair and reads what New Times has to say.

The reviewer has almost everything wrong. He calls characters by their wrong names, attributes incidents to the wrong people, and goes so far as to invent a scene which never takes place. Marty doesn’t know what to say. Whatever mood he was enjoying after his small tour of the city is destroyed. He gets up and walks around the suite. The bellboy arrives and asks if the bags by the door are the ones going downstairs. No one answers him. He repeats the question. Sandy goes over and tells him which bags to take down. “Amazing,” Marty says quietly as he paces up and down, his voice full of disbelief. “Amazing.”

Out in the hall, waiting for the elevator, Sandy hands Marty the inhalator and he uses it.

When everything is in the car, Carl Fasick makes his farewells and Marty gets behind the wheel; and we drive off. He stares straight ahead, saying nothing.

An hour and a half later, as the sun begins to set and make the autumn foliage burn with a hard-edged brilliance, Marty takes a deep breath. “It was like this when we shot some of Bertha. Remember?” he says, turning to Sandy. He is referring to his second feature, Boxcar Bertha, a critical well-received film that achieved secondary notoriety because its star, David Carradine and Barbara Hershey (Seagull), reveled that during the film’s love scenes they had actually had intercourse.

“How long did that take to shoot?” I ask.

“Twenty four days,” Marty says, “It was good discipline. It was important for me to see if I could do a picture under those conditions.”

“I know there really was someone called ‘Boxcar Bertha,’” I say, “but what about everything else: Big Bill Shelly and the unions and his being crucified at the end. Was that true?”

“You can’t get a reality on film. It just isn’t real. Even documentaries, it just isn’t there.”

“None of it. They came to me with a script, and the stars, and asked if I wanted to do it. Many critics said it was an accurate recreation of the ’30s.” Marty laughs. “For me, it was, very clearly, an accurate recreation of the movies of the ’30s, because I wasn’t around in the ’30s. I just know the ’30s from the movies that they made; that’s why the movies opens with a color sequence, which is a pain in the ass, the traditional scene of the girl’s father dying — you always have to have that at the opening I figure, right? You gotta have, ‘Oh, daddy!’ and the girl runs screaming, right? You got to have that. Well, then it goes into a black and white sequence which is a complete old-fashioned time-passage montage and travel, with railroad wheels, you know, railroad tracks, feet walking along them—and, it was just incredible—and then it also introduces the characters again with ‘Barbara Hershey as…’ and there’s a shot of her from the movie later on with the lips moving, talking—made sure I got everybody talking—and of course there’s no sound coming out, literally like the old films. It was the key, to say, ‘Well, look: what you’re watching here for the next 85 minutes is going to be one big homage to the old films of the ’30s and I just hope I can live up to it, to what they meant to me.’ And in some places it does, in some places it doesn’t. It gets very 1970-ish at the very end. Except the last shot is very much a King Vidor, without realizing it.”

The last shot of Boxcar Bertha shows David Carradine crucified on the side of a boxcar. Barbara Hershey stands below, on the ground, staring up at him. The camera is shooting down from above Carradine’s head. The freight train starts to move. Barbara Hershey walks along with it, reaching up to touch Carradine’s feet. The train moves faster and faster. Barbara Hershey is now running along, trying to keep as the body of the man she loves is being taken away from her. “Very beautiful” Marty says, recalling the shot. “I like King Vidor.”

Marty’s deft grip of film as history and craft makes me wonder if his sensibilities have shifted so radically that he doesn’t get the same kick out of movies he used to as a kid.

“Oh,” he says. “I’ll go see something like Legend of Hell House, get very frightened, and enjoy it. And yet I’ll know exactly how they did everything. I can even get wrapped up in Mean Streets in certain parts, even though I know how I cut it. I can actually watch the film and in certain parts get wrapped up and say, ‘I really believe that.’”

He’s taken one hand off the wheel to gesture as he speaks. For a moment the hand hangs in the air, and then drops back onto the wheel as he resumes speaking.

“There was a period when I thought a philosophy, or people with ideas on ways of life, were only in thick books that you could never get through, and I remember a Priest, an old friend of ours, discussing a play in terms of the playwright’s philosophy. And I said, ‘You mean he’s a philosopher?’ and he said, ‘Oh, yeah, yeah. More or less everybody has a philosophy in terms of the way they live, the way they try to figure things out; you find that if a play says something, it’s his philosophy.’ So I began to say, ‘Well, then some of the films I’m watching must have a certain philosophy.’ That’s when I began to realize it just isn’t junk, it’s a matter of what they say to you.”

“Maybe that’s what happened to a lot of the people from your old neighborhood who didn’t like Mean Streets,” I suggest. “Maybe they don’t like what you’re saying.”

Marty shrugs. “I don’t know. A lot of the incidents, a lot of the shootings and things, were similar to things I guess may have really happened. I recall them in different areas, as different things, but they, maybe it’s their paranoia or their own guilt—I don’t know what—they felt that it was a little too close to home.”

“But going home, I mean really going home to tell this story, must’ve been a way for you to get rid of things inside yourself you wanted to exorcise.”

“Oh, yeah,” Marty admits. “Sure, sure. Basically when I went back to start shooting the film. I didn’t want to really see all of my old friends, and all that sort of thing, and then as I started shooting, I got really into it. I realized that we’re much the same people.”

“The whole thing must’ve been like going through a High School Yearbook,” I say.

“Yes,” Marty agrees. “Exactly. And that can be pretty offensive.”

“Or make you feel older and nostalgic.”

“That’s what happened to my friends,” he says.

“Do your close friends look back at those days as being Good Times?”

“Oh, sure. Absolutely,” Marty says. “But it was a nightmare too.” He gives a little laugh. “It really was.”

I don’t quite understand what he means. “In retrospect,” I ask, “or then?”

“Then.”

“You knew it was a nightmare?”

“Sure,” he says candidly.

“Did your friends?”

“Sometimes. I think. Not that they were that intense. Oh, there were a lot of good times, too.”

“Did you see yourself trapped into some sort of life?” I ask.

“Trapped?” Marty asks.

“Like your parents,” Sandy says. Marty’s mother worked in the garment district for forty years. His father works there still, as a presser.

Marty is shaking his head. “Not with a job. But with a young lady I was engaged to. I had gone with her for six years, and while I was making my films I was sort of falling into a kind of pattern where you meet the girl when you’re sixteen or seventeen, get engaged when you’re twenty, get married when you’re twenty-one. That’s what was happening. And then I met a lady who turned out to be my wife, later on, and she tore me out of it. Opened up a whole new thing.”

Now divorced, Marty was married for seven years and he has an eight-year-old daughter, Catherine, who lives in New Jersey with his former wife and her second husband. “We lived together only two of those years,” he says. “It was a constant hassle.” Their wedding had taken place in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 1965. It was a compromise because he had refused to marry the girl everyone had assumed to be his intended. Marrying in St. Patrick’s gave the union whatever spiritual legitimacy may been lost by his rejection of the nice Sicilian girl he wouldn’t marry. The break up of his marriage was closely linked to Marty’s growing doubts about his ability to live the life of a true and faithful believer. He was tormented by visions of his own infidelity to his religion, by the lingering conviction that everything about sex was a sin. One thing that did help push him over the edge and helped him decide to take his secular chances with day-to-day mortality was attending a mass in Los Angeles where the priest called the war in Vietnam a holy war.

“Didn’t you think you might end up like your parents?” Sandy suggests.

“I don’t know what I would be,” Marty says. “I never thought of it. I mean, I did think in terms of maybe being an English teacher, but the main thing in my mind was being a Priest, going back after all that nonsense in High School, going back and finding out exactly what it was really all about because they seemed to have two faces: one towards the kids, which was like monstrous, and the other was The Real Thing, like, ‘Well, of course eating meat on Friday we all know is not really a mortal sin, we just tell the masses that.’ That kind of feelings. I wanted to get in to find all this out.”

Marty began his studies at Cathedral High School. “I was thrown out of there. But I was going to go back, after High School. I failed three subjects, and in Discipline they called me a thug.” From the Seminary, Marty went to Cardinal Hayes High, “for about three years, and many a Summer School in between—’56 to 1960 was High School. 1960 to 1964 was N.Y.U. undergrad. Then I was in graduate school for a year and a half until ’66. Then I taught from 1968 to the end of the fall season of 1970.”

Martin Scorsese seems to never have lost or resolved his ambivalence about the two faces of Catholicism. If he never returned to learn the truth as a Priest, two of his films have examined the effect of such spiritual ambiguity on certain kinds of people. Marty is not at all reluctant to discuss the hold he feels Catholicism can have on a person, a hold which perpetuates that sense of unresolved fealty. As an example, he mentions someone he knows, a former nun, who, “rather than Catholicism, they had her more into the way she dressed, the way she looked—having her bed made—rather than have time to talk about Transubstantiation, or Predestination.”

“‘Ours Is Not To Reason Why’…” I start to say and stop. “It sounds like the Army.”

“Are you kidding me?” Marty says. “It was worse than any Military School. The Priests who was head of Discipline…A guy I knew later, at N.Y.U., saw him on the Staten Island Ferry. He went upstairs, fucking Priest came upstairs. The guy went downstairs. To avoid him. Not that the guy knew him; the guy didn’t even know him. He just didn’t want to be in his presence. He was a nightmare; he used to run around with a cape. Like a vampire.”

He stops and shakes his head as if to give the memory some sort of image so that his recollection will be more than a fleeting resentment. “Every Thursday afternoon there was Benediction given in the Auditorium. We were let out at 2:45 and this Priest wanted everybody to go. We used to have lockers—you open up the lockers, put our books in and our coats and that sort of thing—so the idea was to run to the lockers and run out as fast as you can to skip Benediction because he used to come to the locker and hit you in the back of the head. ‘Get inside! Get in there!’ Grabbing as many kids as he could, throwing them into the auditorium to watch the Benediction. The benediction wasn’t a big thing, it took only fifteen minutes, but the Idea of it…Ohhh.”

It’s getting dark now and all of us are tired, but there’s one more question I want to ask. “Didn’t making Who’s That Knocking at My Door, and now Mean Streets, particularly Mean Streets, didn’t that get a lot of those feelings out of your system? Isn’t it all over for you?”

Marty thinks for several moments. “Yeah, in that particular movie, Mean Streets, it’s gone for me. Sometimes, you know, you’re discussing it, and maybe, the way I directed it, the way I wrote it, made it, doesn’t really tie all the ends. I mean, very often I thought I was doing one thing and I found I was doing another. So, I left it kind of loose. I mean, life never ties up anything, but sometimes you say, ‘Well, Jesus, that must mean I’m really insecure, I really ought to be able to’…” he breaks off momentarily. “Who knows?” he says. “I was really almost trying to photograph reality. That’s why the allusion to The Big Heat at the end of the picture: while the car crash is in The Big Heat is on television, the reality is hitting the streets. But of course,” he adds, “you can’t get a reality on film. It just isn’t real. Even documentaries, it just isn’t there.”

The monotony of highway finally gets to all of us and we lapse into silence. Sandy takes out a cigarette and pushes in the car’s lighter. Marty absently runs his hands around the rim of the steering wheel.

Suddenly, from our right, a large dark blue Pontiac eases up alongside begins to pass, and then starts to pull into our lane, deliberately cutting us off. Marty spins the wheel to avoid our being sideswiped and knocked off the road. As we lurch heavily to our left we get the barest glimpse of the driver of the other car. Anonymous, hair is light color, the eyes barely glance at us; but the look is direct and calculated and we realize absolutely no accident is involved. In the same instance the other driver floors his gas pedal and the Pontiac pulls away from us at ninety or a hundred miles and hour.

Marty is spinning the wheel to the right now. We careen back away from the left lane, the big sedan heaving too far because of the goddamned power steering. Marty spins the wheel back to the left to steady us but we wallow dangerously close to the right lane before we shudder and careen back to our left. It is a speed-driven weave back and forth across the three lanes, which are miraculously clear of any other cars going in the same direction.

“Holy Christ!” Marty is shouting as he wrestles the car to steady it. His voice is surprised and a little angry; there is absolutely no fear, just determination to steady.

Moments later, we are all in the right lane and moving along at a solid sixty miles and hour. “I didn’t want to use the brake,” Marty says. “We were going to fast.”

“What happened?” Sandy asks with the curiosity of the whole incident; she means to know why something so coldly premeditated could happen. How can we absorb the irrational attack of a total stranger?

Other cars pass us, faces pressed to the window to learn what happened. No one seems to understand there had been another car. One woman stares at us with wide eyes and when we look back at her with uncommon calm, she shakes her head; was she expecting a car full of drunks?

“Some of the critics,” Marty says, “there were people who said they didn’t like my movie because some of the violence wasn’t explained enough. Jesus … explained enough.”

We drive Southwest on Route 86 in Massachusetts and we will never know who tried to run us off the road, or why. Do we think a Just God will punish that other driver, or will he reach his destination safely, indifferent to the physical and spiritual confusion he inflicted on us with such casual impunity? Probably the latter, because Marty Scorsese knows that this world is a place where most of us resist the truth of the words which open his new movie:

“You don’t make up for your sins in Church; you do it at home, you do it in the streets. The rest is bullshit and you know it.”