It was practically dawn and the weather, he noted with particular pique, was diabolic. On mornings like these, he preferred to rise late. He liked to walk down to the Yale Club and play a little squash. He didn’t like to hurry. He liked to appear in the office toward the nether side of noon. It was, he felt, an agreeable agenda. Looking at his watch, Sam Cohn hurried out of the rain and into the Gulf & Western Building at the northern end of Columbus Circle. He was late. He was wet. He was tired. Christ, it was nine o’clock in the morning. It was not an auspicious hour.

Stepping into the elevator, Cohn pulled a Kleenex from his trouser pocket and began to tear tiny pieces away with his teeth. By the time he reached the fifteenth floor and had walked down the corridor to the offices of Dino De Laurentiis, he had devoured nearly a third of it. Mr. De Laurentiis, he was told, had not yet arrived. Cohn shrugged and ordered coffee. Strolling into the main office, he sat down in a large leather chair and propped his feet on the producer’s desk. He yawned and looked at his watch. He was an impatient man and had never accustomed himself to delay. Eating the Kleenex, he scanned Dino De Laurentiis’s appointments list, which lay on the desk before him.

Most of the names were known to him—his own, a director, a studio head, and sundry actors auditioning for the leading role in De Laurentiis’s next film. Suddenly, Cohn shifted his glasses above his eyes, examining the list more carefully. “Brinksteen?” he said. “Who’s Brinksteen? Look here. Brinksteen, 10:15. No first name.” The producer’s secretary said she didn’t know who Brinksteen was either. “A nobody?” said Cohn. “Dino doesn’t see nobodies. Well, occasionally Dino sees agents,” he conceded.

The joke amused him momentarily. Cohn himself is an agent. Not one of your upstarts, not one of your commonplace agents, of course; rather, he is a director of International Creative Management, the largest talent and literary agency in the country. ICM represents some 2,000 clients from Ed Doctorow to David Bowie. Cohn is personally responsible for Arthur Penn, Bob Altman, Bob Fosse, Peter Maas, Jackie Gleason, Woody Allen, Dick Cavett, Lily Tomlin, and dozens of other writers, actors, producers, and directors. He is one of the most influential agents in America, acting as a force not only in the film world but in the world of publishing, exerting what is known in the business as accomplished overview. This is particularly notable in his role as “packager.” Traditionally, the agent-packager selected from among his clients a director, an actor, a screenwriter, and then presented that “package” to one of the major studios for the purposes of making a specific film. Cohn refined that technique by incorporating the world of publishing into the initial package. Thus, more often than not, he will come up with the original idea himself, persuade a writer to do it, and then sell the film and paperback rights before the book is even written. He did this with Serpico, and other projects, each of them involving millions of dollars. On this particular morning, Cohn had some similar project in mind, and it was this that had brought him at an odious hour to the offices of Dino De Laurentiis.

A chubby, cherubic man, Sam Cohn has the look of a veteran undergraduate. At 46 he invariably wears crew-neck sweaters over open shirts, baggy trousers supported by a red-and-green-striped Gucci belt, white sweat socks, and what at first appear to be second-hand shoes. He has not achieved this look of nonchalance by chance. Twice a year he purchases a new pair of $80 Gucci loafers; then, using a razor, he snips off the polished bit buckles in order to give them the look of penny loafers. His butchered shoes are an important part of his uniform.

Shortly after 9:30, Dino arrived, immaculately dressed in a light gray suit and an outsized Cartier watch. The two men are old friends and do a lot of business together. They have, in the past, set up many projects—The Vatachi Papers, Serpico, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, and currently, Ragtime. “Dino is one of the few film people who will give you an immediate yes or no,” Cohn had said. “Most of the rest of them are committee men, procrastinators.” Now, Cohn began to outline one of his writer’s original ideas. He told the story hurriedly and with much good humor and after a few minutes of discussion and certain inviolate conditions, De Laurentiis agreed to finance the project. He leaned back in the leather chair. “Sam,” he said, “I hope that while we were talking, the angel of mercy flew overhead and said ‘amen.’ ” De Laurentiis smiled and lighted one of his small cigars. “That’s an Italian expression, Sam, I don’t quite know how it’s said in, uh, English.”

Outside Dino’s office, a group of black men in eccentric dress padded to and fro hoping to catch the producer’s eye. They were actors come to audition for the main role in Drum, one of Dino’s new films, written by the man who wrote Mandingo. Dino peered over the edge of his glasses. “Look at them,” he said. “They’re too American. I need an African, uh, a savage. I need that man who fought Muhammad Ali in the Philippines. You know the one, Sam. You know. I need Joe Frazier.”

Cohn smiled. “Dino,” he said, indicating me, “show him the smell. He only came to see the smell.” Dino laughed and turned away. Earlier, Cohn had explained that Dino, when told of what seemed to be a golden proposition, smelled money and had some baroque gesticulation to illustrate the fact. But Dino declined. Spreading his arms, he said, “Sam … Sam.” Cohn promptly changed the subject. Indicating the appointments list, he asked who Brinksteen was. “I’ve never heard of him,” he said.

“You never heard of Brinksteen, Sam? He’s the biggest pop star in America. The biggest. He was on the cover of Time and Newsweek at the same time. You never heard of Brinksteen?”

“You mean Bruce Springsteen,” said Cohn.

“Brinksteen, Springsteen. It’s all the same to me,” said Dino. “He’s coming in to show me he looks like a gypsy. He wants to play the head gypsy in King of the Gypsies, I don’t know,”

“Can he act?”

Dino shrugged his shoulders and extended his hands. “Act? Uh, I don’t know. He says he’s the gypsy. Maybe we make it a musical.”

Cohn is addicted to the telephone; he looks half-dressed without one in his hand.

At that moment, unannounced, Milos Forman walked into the room. The Czech director was in jeans, a jacket, a long scarf, and a floppy cap. He was in New York for the opening of his film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Sam Cohn and Peter Maas had dined with him the night before to determine if he was interested in directing Gypsies. Forman had liked the idea, but nothing had been settled. “Milos, it will be a great film,” said Dino, “fantastic.” Forman lighted his pipe and said nothing. “Ah,” said Dino, turning to the door, “here’s the gypsy now.”

Springsteen was accompanied by his entourage. The singer came in first. Slightly stooped, he moved across the room in a kind of somnambulant shuffle. He did look like a gypsy. Wearing baggy khaki trousers and a faded Boy Scout jacket, he had not shaved for several days, and a golden hoop dangled from his starboard ear. He had the look of a man who had lost his way several days before. In his wake came his manager and two agents, one black, one white. They were nattily dressed and eagle-eyed. Everyone was introduced. “Is he the gypsy?” said Dino. “Is he the gypsy? Look at him. He’s perfect. He’s got that smoldering look, that, uh, sullen look they have. Do you see it, Milos?”

Somewhat later, the singer and his entourage departed, followed almost immediately by Forman. “Well, Sam,” said Dino, “is he perfect for the part? Sure he is. I’m prepared to give him a three-picture deal.”

Sam Cohn laughed.

“Based on a screen test, of course,” said Dino.

“Do you smell money, Dino?” said Cohn. “Show him the smell.”

As he stood behind his desk, a small shy smile formed on Dino’s face. Extending a long white finger to the tip of his nose, he smote it once, then twice, but delicately; that accomplished, he wrapped his forefinger and his thumb round either side of his Roman nose and shook it fiercely like a tambourine.

Back in his offices at ICM, Cohn’s next appointment awaited him. He had been waiting for nearly an hour. Sam Cohn was almost always late. “An hour late and twenty years ahead of his time,” as one of his colleagues likes to say. Jim Goldman was used to such delays. He had been a client for a long time. A playwright and scriptwriter, Goldman had written, among other things, The Lion in Winter. Cohn walked behind his desk and asked Goldman to wait while he took a call.

Cohn rarely sits down; rather, he seems to sprawl in his chair and now, as he had done in Dino’s office, he sank back and put his feet up on the desk. His office is relatively free of ornament—a desk, three chairs, a sofa, bookshelves behind him. On the walls are posters of recently released films, a New York City fireman’s hat given to Cohn by those members of his staff who had been trapped with him on the eighteenth floor during a recent fire, and a drawing by Herb Gardner entitled The Negotiation. It depicts a covey of agents in full cavil. “The effluvia,” said Cohn, “is accurate.”

Cohn is addicted to the telephone; he looks half-dressed without one in his hand. Slumped in his chair, he had slung his right arm round the back of his neck to hold the phone to his left ear. As he talked, he chain-smoked Camel cigarettes, occasionally closing his eyes and twirling the ends of his tousled hair. He receives more than a hundred calls a day. The calls, listed in triplicate, are safeguarded by a secretary and an assistant. His busiest day to date, his secretary recalls, was the day he received 353 calls. His telephonic technique is friendly, jocund, chiding, often ribald, and punctuated with a shrewd comprehension of money, of propositions and points and bottom lines. His conversation is cluttered with such phrases as “if I may suggest … ” or “I thought what we meant was … ” or “as I’m sure you know.”

While Goldman waited, Cohn took one call after another. His talk skimmed across the room like a series of admonitions from the wings. “I know he’s a friend of yours, George, so I’m giving you a friendship discount, okay? … ” “What d’ya mean you’re difficult to reach? Do you have a telephone? Are you hooked up to the outside world? You are? Well then, we’ll be in touch …. ” “Listen, Jerry, I can’t talk to you now. By talking to you, I’m keeping an important scriptwriter from getting a job.” Some 30 minutes after he had sat down, Cohn shouted to his assistant: “Cathy, cut it, shut ’em off, I’m not talking anymore.”

Jim Goldman had come to Cohn with the bare plot of a film idea which he had written on a sheet and a half of paper. The film was to be called The Foundation and it took him less than five minutes to describe it to Cohn. When he had finished, Cohn leaned back in his chair, lifted his glasses, and rubbed his eyes. Then, sitting up, he smiled. Like all persuasive men, he smiles a great deal. “It’s a certain winner,” he said. “We can get a bundle of money for this. Leave it with me and I’ll get back to you at the end of the week.”

Goldman was wonderfully pleased, not only for promises of serious cash, but because he preferred to write his own screenplays rather than adapt the work of others. Standing up, he said: “May I kiss you on the forehead, Sam?” Cohn grinned. Goldman walked round the desk, and leaning down, he kissed the agent on his pate.

When Goldman had gone, Cohn explained that he had had long relationships with his clients and that they were very close. “You see, the stereotypic notion of agents has always been that they’re flesh peddlers,” he said. “It used to be when you thought of an agent, you thought of a Broadway character, a disadvantaged, uneducated manipulator who thought only of his 10 per cent and would have sent his clients to Hades in order to get four bucks. But all that’s changed drastically.”

“There’s just enough action in New York.” He grinned. “Just enough.”

Cohn had come into agentry by accident. Hired out of Yale Law School by CBS, he had spent nearly two years in a remote office distant from everyone else working through piles of contracts on which were the names of people he wished to know, but didn’t —names such as John Frankenheimer and Arthur Penn. He spent nearly two years negotiating contracts and then worked with Hubbell Robinson on the production of a special series of television programs for the Ford Motor Company. They were not successful, and he resigned. Although he had always hated practicing law, between 1960 and 1964 he worked for a New York law firm. During this period, he also produced several Off-Broadway plays—“plays you never heard of”— such as Red Eye of Love and Elaine May’s Not Enough Rope. In 1964 he moved to the General Artists Corporation as executive vice-president and agent. In 1968 GAC was taken over by Creative Management Associates and in early 1975 CMA merged with International Famous Agency to become ICM. At that time he was offered a position as head of production at one of the major studios, but turned it down: “I could never function as part of a corporate committee,” he said.

“I’m a director of this company now,” said Cohn. “In terms of being an agent, I have a free hand to do what I feel like doing. I don’t have to worry about the stockholders or going down to make speeches to the security analysts anymore. I don’t have to worry about hiring and firing. But like everybody else in the free-enterprise system, I have to make a justification for the money I earn.” (Cohn earns $150,000 a year, plus additional benefits.)

“My job is to get people work and get movies made,” he said. “A good part of my job is to help my clients decide what not to do. And I have to protect their privacy. I mean, if Jackie Gleason had to read every memo and every script, if he had to listen to every request, he’d have no time to survive. Agents don’t have omniscience, of course. I discuss every serious proposal with my clients directly and always consider whether the proposal is valid in terms of their overall career. For example, there’s a shibboleth—well, maybe it’s a shibboleth and maybe it isn’t—but there’s a shibboleth that goes, ‘If you’re on television and people can see you for nothing, they will not then go out and pay $3.50 to see you in the movies.’ That kind of thing must always be taken into account.

“I actually like my job. You move constantly from one project to another and from person to person. You’re dealing with real and imagined peaks. It’s a very immediate job. As my friend Herb Gardner once said: ‘Sam, you’re doomed to live in the present.’ ”

At 2:30 that afternoon, Cohn had an appointment with George Barrie, president of Fabergé. Just before three, we set out for his office; Fabergé was three blocks away and Cohn wanted to walk.

“You know why I work in New York?” he said. “The main reason for being here, outside of the fact that I prefer to be, is that all the different disciplines are here and so are many of the creative talents. The Chayefskys, the Nicholses, the Woody Allens. Journalists, publishers, directors, actors, producers, artists, they’re all in New York. And I’ve tried to learn to cross-pollinate those various disciplines.

“Los Angeles is impossible. In Los Angeles you can have a life, and a horrible one; you can even have a career and deal with Warner Bros. and Paramount, but not me. I wouldn’t live in California if they offered to pay me in gold bullion at the end of every day,” he said. “Listen, if you’re Bob Altman, let us say, and you want to live on the beach at Malibu and you know you’re not going to be stuck there for more than three months out of twelve, that’s great. But if you’re Sam Cohn and you know you’re locked into L.A. for 40 out of the 52, screw it.” Like Gertrude Stein, Cohn had come to believe there was no there there.

“In New York,” he continued, “you can talk to people not directly connected with the film business. There’s just enough action in New York.” He grinned. “Just enough. The different disciplines exist within twelve blocks of one another. One can literally go in a direct line almost from my office to Bantam Books, to United Artists, to the Shubert Theater. And, if you wanted to, you could stop by CBS or ABC on the way and you wouldn’t even have to take a cab. On top of that, should you want a little kick, you might even go to Fabergé. Which is where we’re going now.”

George Barrie’s office at Fabergé is a kind of futuristic wonderland. Cluttered with multicolored neon tubes, suspended televisions, a mirrored bar with sculptured figures before it, a projection room, and geometric domes containing toilets and powder rooms, it seems more of a laboratory than an office. As we entered the main room, from somewhere in the bowels of the masonry, a sultry female voice announced: “It’s three o’clock.” Sam Cohn looked around, but there was only George Barrie sitting behind his spacious desk. When not running Fabergé, Barrie is an independent producer. He heads a company called Brut Productions, which has produced, among other films, A Touch of Class. It is an amusing irony.

Sam Cohn had come to see Barrie on various matters, and when they had settled their business, he casually brought up the idea for The Foundation. He had told the story once before that day to another producer. He knew the story perfectly now, but had taken to adding bizarre embellishments that had not existed in the original. Barrie listened patiently. When Cohn finished, he said, “What do you think, George? It has real possibilities.” Barrie asked about the script, how much it would cost and what the up-front moneys would be. Finally, he shook his head.

“It’s not a bad idea, Sam. I’m not saying that. It’s just not for me. I’ve got too many projects I really want to do at the moment.”

“Well, I’m not really trying to sell it to you, George. I just thought I’d mention it while I was here.”

“Then, why are you here?” said Barrie.

Cohn grinned. “It’s because I like you, George. I haven’t seen you since yesterday. And besides,” he said, looking around the room, “this is an amusing place to visit.”

“I’m sorry, Sam,” the producer said. “It’s not for me.”

Back in his own office, slumped behind his desk, Cohn embraced the telephone. Should a call fail to materialize instantaneously, he will suddenly shout at his secretary: “Scotty, there’s a priority of calls. Get them, goddamn it.” Looking around the room, he said, “Do you get the feeling that synapses are being missed this afternoon?” He began to snap his fingers. “Come on, Scotty, come on. I want those calls. Get me Lily, then get me Eric and Bob and George and Jerry. In that order. I don’t have all goddamn day.”

On the telephone he was wonderfully convincing; he displayed the fluent charm of an accomplished confidence man. “Hello, darling, I really miss you. Did you get that? Now, that’s a preamble for the following …. ” “Listen, Zero, I’ve made the deal. I’m in the position of an orthopedic surgeon. I’ve set the bones. The rest is up to you …. ” “The problem with your goddamn company is that while that man is flying in the air, nothing gets done. Do y’hear? Outrage is dripping off my lips …. ” “Listen, we can’t sleep with you until we get out of their bed. You know that …. ” “Hello, Mr. Fields. I’d just made a decision not to talk to you again. Why? Because you haven’t called me and my feelings are hurt.”

Toward six o’clock, a call came through from John Calley, then president of Warner Bros. “Hello, John,” he said. “I’ve never heard you sound so sunny.” Cupping his hand over the telephone, he grinned and said, “Well, he sounds sunny.” The two men discussed some minor business, asked after each other, and bantered about the state of moviedom. At this point, Calley mentioned The Foundation, saying that it had been presented to a colleague of his but that he had not quite understood its intricacies. Again, Cohn launched into a long synopsis. Never had he surpassed this telling; it was as though he had seen the film the day before. Every scene, every shift in the plot he recounted with skill and high panache. When he had finished, he paused and said, “Well, John, what do you think? Is that not a great idea?” Cohn adjusted his bulk in the chair and closed his eyes. Nearly a minute passed and slowly Cohn began to smile. Listening closely, he lifted his thumb into the air. A minute later, he put down the phone. “Well, it’s sold,” he said. He stood up. “Cathy,” he screamed at his assistant, “get me Jim Goldman on the line. Immediately.” Three weeks later, a contract was signed.

At nine o’clock Cathy prepared to leave. Coming into Cohn’s office, she reminded him he had an important call to make at ten o’clock. Cohn wrote the number down on the inside flap of a book of matches and bid his assistant good night. As she left, Bob Altman arrived. Altman had recently completed Buffalo Bill and the Indians and had come to New York to begin work on the script of Ragtime with Ed Doctorow. Altman sat down. Sam Cohn took out the backgammon board and with scarcely a word they began to play. The two men are close friends and like to bet with each other for humble stakes at backgammon, and on baseball and football games. Neither of them is particularly good at backgammon, but they played with a kind of inspired ineptitude.

As they played, Cohn began to talk of some of his favorite projects. “Lenny was an important deal,” he said. “Bob Fosse wanted to do it and ultimately we put it together, but only after the most incredible problems. That film will end up grossing $18 million to $20 million, and it was also a considerable artistic success. I was really proud of that. It’s easier to make that kind of imaginative deal in New York than anywhere else. A perfect example is King of the Gypsies. It was Peter Maas’s idea. He didn’t want to commit himself to writing the book, so I talked him into doing a couple of magazine articles in order to legitimize the project. I wanted to package this deal beforehand. I knew it was an obvious movie. So once the articles were written, I went to Dino with the idea.”

Cohn grinned. “I’ll never forget it,” he said. “I hadn’t even completed my second sentence before Dino smelled money. Real money. Peter was there, he can tell you. Dino rocketed up from behind his desk, and grabbing himself with his right hand, he jumped up and down, shouting, ‘That’s it, that’s it. Peter, you can write it right from here. It’s big stuff.’ Well,” said Cohn, “after that display, I went to Bantam Books right away and sold them the paperback rights. Bantam is a very effective publishing house and they’re very conscious of movies. In cases of this kind, the hardback houses don’t count a great deal. In economic terms, to deal with them is just plain silly, but they do give a certain patina to the transaction. In the end, Bantam went to Viking with the book, but the writer had made his real money long before then.” As do all of ICM’s clients. Five of them, for example, were involved in the making of Serpico: Frank Serpico himself; Peter Mass, who wrote the book; Waldo Salt, who co-wrote the script; Sidney Lumet, who directed the film; and Al Pacino, who played the leading role. Among them they earned about $3,75 million—and ICM, of course, took 10 per cent.

The two men continued to play, Cohn nibbling at a book of matches. “Of course, it’s not all that easy,” he said. “Sometimes, you just can’t move a deal. Sometimes you make mistakes. I thought the idea of Dog Day Afternoon, for example, was madness. I didn’t think people would be interested in the basic notion of a homosexual marriage. I passed. It was a mistake in judgment.” He smiled. “I’ve made many.”

It was ten o’clock, Altman had an appointment, but said that he would meet Cohn later. As Cohn walked out of the office, he remembered his telephone call. Walking back to his desk, he rummaged through papers and under the backgammon board looking for the book of matches. He looked up suddenly. “My God,” he said, “I’ve eaten it.”

Down on the street, Cohn laughed and said he was still hungry. He laid a hand on his prodigious girth. “I’ve got to learn to keep my hedonism in hand,” he said, and he scurried into the Two Bears for a Tab and a bowl of chili.

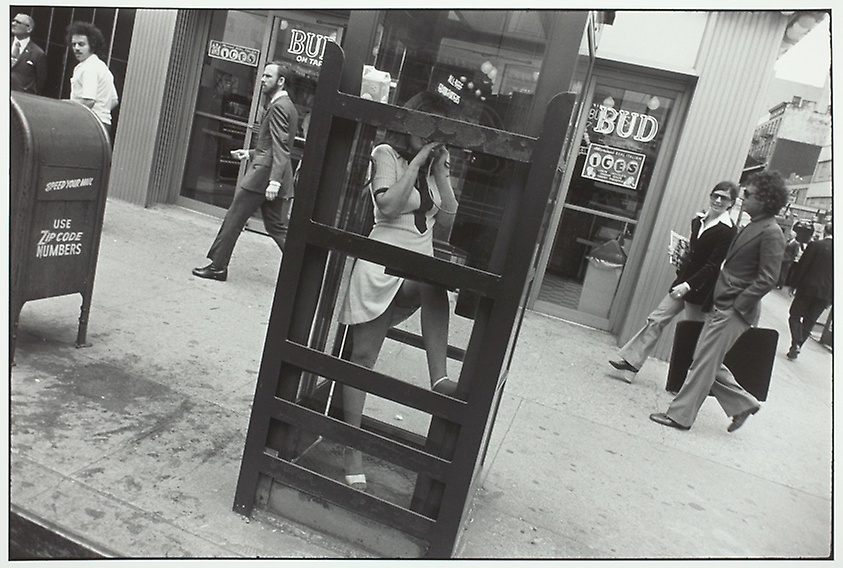

[Photo Credit: Garry Winogrand c/o The Art Institute of Chicago]