The publication of a book is not often a major event in American culture. Most of our classics, when they first appeared, met with disappointing receptions, and even the much-ballyhoed best-sellers of recent years have rarely cut a great swath outside the lanes of publicity and journalism. But this year a real literary-cultural event portends and every shepherd of public opinion, every magus of criticism, is wending his way toward its site. Gathered at an old New York City inn called Random House, at the stroke of midnight on the 21st of February in this 5,729th years since the creation of the world, they will hail the birth of a new American hero, Alexander Portnoy. A savior and scapegoat of the ’60s, Portnoy is destined at the Christological age of 33 to take upon himself all the sins of sexually obsessed modern man and expiate them in a tragicomic crucifixion. The gospel that records the passion of this mock messiah is a slender, psychotic novel by Philip Roth called Portnoy’s Complaint (the title is a triple pun signifying that the hero is a whiner, a lover and a sick man). So great is the fame of the book even before its publication that it is being hailed as the book of the present decade and as an American masterwork in the tradition of Huckleberry Finn.

Heralded last year by several stunning excerpts in the serious literary magazines, Portnoy comes to us glowing not merely as a succes d’estime but as a succes de scandale—the scandal fuming up from the book’s pungent language, a veritable attar of American obscenity; and from its preoccupations, foremost among which is the terrible sin of onanism. Presently the object of a cult, which passes selections from the sacred writing from hand to hand at sophisticated dinner parties so that all may have the opportunity to read aloud, Portnoy today is still an underground password. But the complete work is being readied for distribution by an international ring of literary agents who are cutting, packaging and peddling it like a deck of pure heroin. Soon it will be injected into every vein of contemporary culture: as hardcover book, as soft-cover booklet, as book club offering, as foreign translation and as American. The TV rights remain as yet unsold, but even without them the book has already earned almost a million dollars prior to the first press run.

A million dollars in publicity is what the book will earn next. A chain reaction of cover stories and profiles and critiques and put-ons and put downs and pictures and cartoons and slogans and quips has already begun to build toward a blast that may set a new record for publicity overkill.

The book that is being blown up by all of this puffing is not so much volatile as it is intense, probing, incisive. A diagnostic novel by a comic Freud, it focuses its lens of a beautifully cut and brightly stained slice of contemporary American life—all sick, black and blue. The hero, an Assistant Commissioner of Human Opportunity for the City of New York, is a man who exemplifies the cherished values of the Kennedy years. Brilliant and precocious as a student, successful as a lawyer, dedicated and sensitive as a public servant to the underprivileged, Alexander Portnoy has devoted his whole life to being good.

Portnoy cannot escape the appalling fact that in the ’60s Americans are seeking to live by two completely contradictory moral codes.

Yet when we discover this nicest of Nice Jewish Boys, he is lying on his back on a psychoanalyst’s sofa, like an overturned cockroach, spewing out a frenzied stream of angry, resentful and self-defensive words. Honking through his beaky nose a heavy Jewish blue, he reels off an endless chronicle of suffering, degradation and terror, interspersed now and then with little grace and notes of pleasure.

Though Alexander Portnoy’s complaint is directed in the first instance against his smothering and seductive mother, and in the second against the succession of maddening females who have poisoned his life, the ultimate truth of his condition is that he has fallen victim to American history in the same way that Oedipus fell victim to fate. For struggle as he will, and analyze as best he can, Portnoy cannot escape the appalling fact that in the ’60s Americans are seeking to live by two completely contradictory moral codes. Maintaining their allegiance to the traditional morality of monogamy, fidelity, self-sacrifice and the sublimation of sexual energies, Americans are almost equally sanctimonious about those “needs” and “rights” that include the license to experiment with every sort of sexual and sensuous behavior dictated by the most primitive instincts and passions. Walking about in a fallen world, with these two Edens warring in their heads, modern Americans are made borderline schizophrenics.

Something of this sense of the Doppelganger that stalks us has been suggested in a great many works of contemporary literature and comedy. Indeed, the farcical gap between what all Americans are supposed to be and what they are has been the mainstay of our humor ever since this American dilemma found expression in the wit of the so-called “sick” comics of the mid-’50s. Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl and Nichols & May were the first to exploit the awkward, spraddling moral stance of the new American; after them the comedy of the Yankee schemiel was developed much further by a whole succession of Jewish novelists, including Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, Wallace Markfield and Bruce Jay Friedman. For more than a decade these comic artists cultivated the themes and techniques brought to final fruition in Portnoy. For it has always been evident that, though this profound conflict between our better and worse selves might tear us apart, drive us to despair or make us crazy, it could never be treated with complete seriousness or with the literal-minded simplicity of the sexologists and the public moralists. Comedy alone could provide the lens through which this strangely contorted and grotesquely embarrassing American predicament could be examined.

Philip Roth’s achievement in Portnoy, therefore, is not the discovery of a theme nor the invention of a mode, but the final perfection of an art, the comic art of this Jewish decade. His book combines in its irresistible funniness all the resources of the tradition: the relentless Marx Brothers energies of Catch-22, the self-pitying rhetoric of Herzog, the hovering Chagall figures of Stern and A Mother’s Kisses, the pop art sprinkles of To an Early Grave and the self-lacerating ridicule of Lenny Bruce. Purging the Jewish joke and comic novel of their lingering parochialism, Roth has explored the Jewish family myth more profoundly than any of his predecessors, shining his light into all its corners and realizing ints ultimate potentiality as an archetype of contemporary life.

Portnoy’s Complaint boldly transcends ethnic categories. Focusing its image of man through the purest and craziest of stereotypes, the book achieves a vision that, paradoxically, is sane, whole, and profound. As intimate as the mirror on the bathroom wall, it affords its readers glimpse after glimpse of themselves nakedly living the truths and lies of their innermost lives. Looking into this mirror, the reader—Jew or Gentile—will be caught between the instinct to cover up and the urge to bare all. Torn, yet relieved by successive shocks of recognition, he will murmur the healing formula of self-acceptance: “It is I.”

So intense is the conflict between the two sides of Alexander Portnoy’s fractured psyche, so classically clear is his syndrome, that he has been accorded by his psychoanalyst the signal honor of having his illness defined by his symptoms and labeled with his own name: “Portnoy’s Complaint—A disorder in which strongly felt ethical and altruistic impulses are perpetually warring with extreme sexual longings, often of a perverse nature…Acts of exhibitionism, voyeurism, fetishism, autoeroticism and oral coitus are plentiful; as a consequence of the patient’s ‘morality,’ however, neither fantasy nor act issues in genuine sexual gratification, but rather in overriding feelings of shame and the dread of retribution, particularly in the form of castration.”

Portnoy’s personality derangement derives, of course, from his childhood relationship with his Jewish mother. Alternately rocked in the soothing seas of maternal solicitude and swamped by the terrifying tides of maternal domination, the boy grows up pathetically seeking some one thing he can call his own. Not until puberty does he discover what he is seeking. Masturbation offers him the thrill of a secret, rebellious and wholly self-indulgent life. Behind a locked bathroom door, his head thronging with erotic images, his ear alert for the terrifying knock and unanswerable challenge—“Alex, what are you doing inside there?”—Portnoy comes to identify sex with feelings of anxiety and remorse. But the power of his secret pleasure propels him out into the world in search of the beautiful, responsive creatures of his fantasies. Gentile girls with silky hair, button noses and long slender legs are what he seeks: little beauties redolent of the perfume of America, the alien land that must be plowed to be possessed.

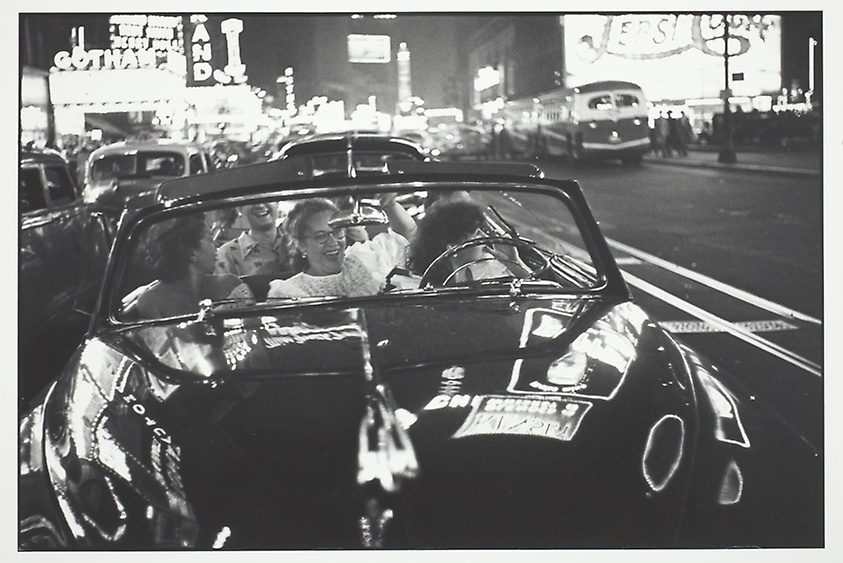

Questing like a nervous knight-errant in search of an erotic grail, he must pass through many encounters, many trying adventures, before he discovers the embodiment of his dreams standing at midnight on the corner fof 52nd Street and Lexington Avenue. Springing off the highboard of life-as-fantasy with this girl, who is so appetitive and ignorant that he calls her “The Monkey,” Portnoy tumbles head over heels in the most extravagant of all erotic, romantic, neurotic relationships. Their dreamlike fall into the depths of sexual debauchery is at first thrilling—in this respect paralleling the stolen pleasures of his boyhood. But gradually they come to demand something more of each other than exchanges of erotic goodies, and the relationship splinters into angry words and exacerabated feelings. Finally, after having inveigled his mistress into a scene of climactic licentiousness, our hero abandons her as a crazy person who menaces his life and happiness.

Leaving the hysterical Monkey standing on the window sill of their hotel room in Athens, threatening to dash herself to death on the pavement below, Portnoy flees to Israel, where he meets a lady kibbutznik, a rugged, self-righteous amazon who reminds him of his mother. Attempting a crude physical seduction, he finds himself impotent. When he offers the lady an alternate form of gratification, she becomes enraged at his degeneracy and kicks him in the heart. Ending his sexual odyssey much where he began it, sprawling prostrate and helpless at the feet of a greatly desired but inaccessible woman, Portnoy concludes his long complaint with a protracted scream of pain.

Portnoy is not only a funny but an impassioned and angry book. Unlike every other Jewish writer since Heine, Philip Roth knows what’s hurting him—and it isn’t the goyim. He delivers his most soul-gratifying thrusts at those sentimentalized objects of mindless piety, the Jewish mama and papa, the emasculators of generations of Jewish men. Yet his anger is crossed by love for its targets, and is distinguished even further by an “Arise Ye Brothers of —–” ardor, a rhapsodic sympathy for his fellow sufferers that bursts forth in passages of ironic eloquence. The crown of the book is his vision of a Jewish Ship of Fools, a boatload of Nice Jewish Boys rolling on the seas of guilt:

“I am in the biggest troop ship afloat … only look in through the portholes and see us there, stacked to the bulkheads in our bunks, moaning and groaning with such pity for ourselves, the sad and watery-eyed sons of Jewish parents, sick to the gills from rolling through these heavy seas of guilt—so I sometimes envision us, me and my fellow wailers, melancholics and wise guys, still in steerage, like our forebears—and oh sick, sick as dogs, we cry out intermittently, one of us or another, ‘Poppa, how could you?’ ‘Momma, why did you?’ … the retching in the toilets after meals, the hysterical deathbed laughter from the bunks, and the tears—here a puddle wept in contrition, here a puddle from indignation—in the blinking of an eye, the body of a man (with the brain of a boy) rises in impotent rage to flail at the mattress above, only to fall instantly back, lashing himself with reproaches. Oh, my Jewish men friends! My dirty-mouthed guilt-ridden brethren! My sweethearts! My mates! Will this … ship ever stop pitching? When? When, so that we can leave off complaining how sick we are—and go out into the air, and live!”

For many readers the strangest feature of Portnoy will be the fact that its author is the same man who wrote Letting Go and When She Was Good, books that reveal Roth’s moral preoccupations and literary skills but in no way prepare one for the high jinks of this latest work (though these high jinks do in fact mirror closely the style and wit I and other friends of Roth have enjoyed for years in private conversations and at parties). Indeed, since 1960, when at the remarkably early age of 27 he won the National Book Award for fiction with his first work, Goodbye, Columbus, Philip Roth has given every indication of desiring to be counted among the handful of recent authors more concerned with the values of traditional literature than they are with the currents of contemporary writing.

Educated at Bucknell and the University of Chicago, active for many years as a teacher of English literature and creative writing at Chicago, Princeton and Iowa, a familiar figure on the college lecture platform and even behind the lectern of the synagogue, a contributor to Commentary and Partisan Review, Roth has clung through his whole career to the skirts of the university and has counted himself a member of the intellectual and cultural elite. It was to this audience in particular his work appealed.

After 15 or 20 minutes of this comic fuguing, the waiters would be throwing Philip looks, Wall Street Journals would be dropping and some old lady would be giving him the top lens.

With Goodbye, Columbus, a collection of canny, morally sophisticated stories written in a scrupulously impersonal style—the antithesis of the verbal extravagance of Portnoy—Roth focused fiercely on the life of middle-class America in the postwar years, particularly in the American Jewish community where all the traditional values were being submerged in the scuffle to obtain the good things of material prosperity. This volume was followed in 1962 by Letting Go, a long and thoughtful novel in which Roth articulated his moral obsession, the theme which underlies all his subsequent writing: the effort of the self to break the bondage of narcissism by renouncing all selfish gratification in favor of a self-sacrificing dedication to the happiness of others. This Christian theme he treated, of course, with a great deal of irony, steadily increasing the dosage, until in Portnoy the theme is totally inverted and the hero struggles, with the reader’s covert approval, to cast off all traces of moralism and lead a life of guiltless self-gratification.

It was while he was working on his third book, When She Was Good, that I first met Philip Roth. Whether it was owing to some congeniality of temperaments or simply to the fact that he knew that I had spent a great many years running with a pack of Jewish comics that included the late Lenny Bruce, our encounters soon assumed the form of spontaneous staging sessions with Roth out in the spotlight working the room like stand-up comic. Typically we would meet by chance at the Mayhews, a little breakfast shop in Manhattan’s East Sixties. I’d be sitting there enjoying the peace of the morning hour and the soothing influence of an egg and butter, when my mood would be shattered by a reproachful voice: “Albert, your father and I have been worried sick about you!” Looking up I would see, not my Jewish mother magically transported from Santa Monica to New York, but Philip Roth, glaring at me maniacally. Looking nothing like the picture of the jackets of his books—that beautiful fem-man face, with its cleft Cary Grant chin, bold intellectual nose and distantly gazing Mesmer-eyes—this was the comic-crazy Roth, the one lost soul on the pilgrimage, a jarring presence in sending out hysterical waves in every direction.

Slipping into the chair next to mine, fixing me with a hooded maternal gaze, he would continue his exhortation in that guilt-inducing, this-is-not-your-mother-but-your-conscience voice: “Two weeks and not a word. How is it a writer, a person who sits all day behind a typewriter, can’t put two words together to send to a mother who lives three thousand miles away?” Then a hyena laugh, fracturing that sorrowful maternal stare into the crazy lights and angles of a Cubist portrait. I’d be gagging, choking, caught between laughter at Philip and anger at my mother, wondering meanwhile (with an instinct as old as the race) what the goyim were thinking—particularly that thick-lensed cashier, who has stopped toting up his bills and is staring with astonishment at this strident newcomer.

By this time Philip would be too wound up to notice or to care what reaction he was getting. He’d be doing the Jewish Genet who has written this play called The Terrace in which there’s a brothel for Nice Jewish Boys where you go every night and they dress you in Dr. Denton’s kiddie pajamas and they bathe you and powder you and put mineral oil where it itches. Tucked into your bed, you fall asleep blissfully listening to a little radio with an orange dial. Next morning a voice calls softly, “Wake up, dear, it’s time to get up.” For that, Philip says, he’d gladly pay $50 a night.

Now the magic word “radio” triggers him into his “Blue Network” bit. “J-E-L-L-O!” He’s doing all the voices from the Jack Benny show: smoothie Jack, fruity Dennis. Yes, yes, I remember them perfectly! But wait, he’s reaching even further back for—wow!—Mr. Kitzel! Now he’s sliding his voice way up in the air in an oral shrug, a vocal curlicue: “Mees-ter Benny!” Oh my pop epiphany, it’s Schlepperman! “Awesome, Philip, awesome.”

After 15 or 20 minutes of this comic fuguing, the waiters would be throwing Philip looks, Wall Street Journals would be dropping and some old lady would be giving him the top lens. Everybody would be asking himself, “Who the hell is this guy? He must be some famous Jewish nightclub comedian who hasn’t gotten to bed yet. Wow! He’s really up there. Nine o’clock in the morning and still flying.”

After all my years with the funny men, my response to Philip’s antics was partly professional. I recognized in him a type not of the stage but of the Jewish living room, the candy store or luncheonette, where after school the kids take turns driving each other over the edge into hysteria. He agreed that he had learned to be funny when he was a child, probably on those daily walks from Chancellor Ave. grade school in the Weequahic section of Newark to the little Hebrew school 15 minutes away. In that precious quarter of an hour, those highly regimented Jewish kids could blow off steam and subject the pyramided pieties of their world to a healthy dose of desecratory humor. For a few minutes they could afford to be bad.

Being bad and being funny were much the same thing in Roth’s mind, and I often had the feeling that when he wrote his fiction he was intent upon being very good. Having as one of my own obsessions the ideal of a Jewish comic who would be an artist and not just a theatrical or literary entertainer, I often urged Roth to exploit his comic gifts in fiction. I told him that his role was to be the comic messiah, the redeemer of the Jewish joke. When I pressed my arguments and exhorted him to write a novel that would match his hidden talents, a book that would be black, sick, surreal, Kafkaesque, unabashedly vulgar, obscene and Jewish, he would say with a sigh, “Oh, Al.”

In those days, When She Was Good was his primary obsession. He had worked on it for years and rewritten it something like eight times. In his apartment were four big cartons stuffed with manuscript. After so many years of close-up work, he couldn’t tell any longer what he was doing; so one day he packed the latest draft into his briefcase and left his rackety apartment for the calm of the 42nd Street Library’s reading room. There he read enough of what he had written to realize that, despite the enormous pains he had lavished on the book, it was still so defective that he could not think of publishing it. Walking out into Bryant Park with its pigeons and hobos, he contemplated the future. No longer was he a writer, he decided, nor would he trade off his literary reputation by taking a succession of teaching jobs. At 33 he was young enough to go into something else. What would it be? Well, he could always go up to Harlem and be a playground director and die.

Instead, he went off to Yaddo, a foundation-supported estate in Saratoga Springs, which serves as a work retreat for writers, artists and composers. (Roth’s deep attachment to Yaddo owes something to the beauty of the place—it is set among lakes and woods, with a view of the distant Vermont mountains—but it is really its character as a sanctuary from city life, and more especially its comfort as a surrogate home, a home without the annoyance of a family, that explains his frequent and prolonged visits there.) Regulating his life for as much as six months at a time by the soothing routine of the place—they get you up early, feed you breakfast and pack you off to work in a little cabin with a lunch box full of cold chicken and a shiny apple—he was finally able to bring When She Was Good into order and to publish it in 1967.

“A terrible mistake has been made.”

A stylistic tour de force, When She Was Good turns the tone of One Man’s Family back on itself to produce a highly ambiguous literary texture whose irony is as subtle and deadly as the ripple in a highly polished saw blade. The tension of the book is generated by counterpointing the most gracious of all pop American tones against the moral frenzy and insanity of the heroine, a Midwestern Medea who embodies the horror of the Protestant ethnic run amok.

Expecting high praise—at least from the more sophisticated critics—Roth was dismayed to find the reviewers yawning over his novel and offering consoling phrases while they waited for his next book. Perhaps When She Was Good was too subtle for those who sat down to write about it. In any case, as soon as Roth had finished it his mind righted itself and all the baffled energies that had blown this way and that during five years of mental doldrums now became a steady breeze which soon shaped itself into a voice—a voice rising and falling with the complaining intonations of an angry and neurotic Jewish boy.

For two years I had seen so little of Philip Roth that when I dialed his number last summer I wasn’t even sure whether he was still living in New York. But having read the fourth instalment of Portnoy’s Complaint in New American Review, I had to toss in my penny’s worth of praise. Always glad to hear from an old playmate, Philip invited me to his home in one of New York’s tallest and baldest buildings. As I walked into his apartment on the 21st floor, a flat lined with the brown metal bookcases like the stacks of a library, he greeted me with a routine, singing in the strident voice of a Broadway musical comedy star, “New York, New York, it’s a wonderful town!” and gesticulating toward the huge plate-glass windows of the room. Holding a high note, he drew the blind to reveal a stunning panorama of the city skyline.

Stepping offstage, he slumped into an armchair and began to talk. Immediately, I caught a new note in his voice, a lilting note of optimism.

“Wow, what a year I’ve had!” He reels off an incredible yarn. It starts with his going to a publication party for William Styron’s Nat Turner. Standing there in his new British tweeds, nibbling on an hors d’oeuvre, Philip begins to feel this pulsing pang in his right side. He’d had the same pain months before and figured he’d licked it, but now it grows worse and worse. The doctors can’t tell what it is, so they put him in the hospital and his fever goes up and up, and finally, this crazy scene: A big, handsome surgeon dressed for a black-tied party is pressing down on his abdomen and Philip is going through the ceiling. Appendicitis is the diagnosis and immediate operation the plan, but when they cut him open they find that the cap blew off his gut days before and his belly is flooded with pus. They stick tubes into him from top to bottom and for days he wallows in delirium. Every time he comes out of it, he finds this exquisite woman, the woman he’s been seeing almost every day for three years, standing at the foot of the bed wearing these strange sacklike dresses. “Get out of here!” he screams. “Go home and put a short skirt on. You look like you’re dressed for my funeral” (And indeed, as he learned later, by the time they cut into him he was just two hours’ walk from the grave—a shocking realization that flooded him with an awed feeling of pride and elation. He had wrestled the Malekhamoves—the angel of death—to a fall.)

Then there is his convalescence in Florida, an idyl of sun and water, and the finishing touches of Portnoy, and the growing feeling that he has his life back under control at last, when one morning, in this same living room—he’s up on his feet now, showing me what happened—the phone rings and he hears his step daughter saying, “Mother has been killed.” His estranged wife, Maggie, being driven across Central Park at five in the morning, had been instantly killed when the car smashed into a tree. Philip is stunned. He goes through the funeral arrangements in a trance. Then, just as he starts to pull himself together again—wham!—all the hullabaloo begins about Portnoy. Fame he’s known before, but now, for the first time in his life, he has money—and everybody is shooting zingers into him. He passes the man next door, who says, “Oh, my neighbor, the millionaire!” But what can Philip say? Yesterday a messenger came to his door and gave him a royalty-advance check for a quarter of a million dollars. Philip gave him a tip. What’s the tip on a quarter of a million dollars. Philip gave him a tip. What’s the tip on a quarter of a million? “I gave him a quarter, Al.”

Now he’s into this new book. He doesn’t know where he’s going: he has all these pieces of paper with one sentence on each page. He’s just writing this stuff and throwing it away, groping for a new theme—some bit semi-comic idea. And he’s haunted by this phrase, a simple little phrase: “A terrible mistake has been made.” Just that. Now he thinks he may write a book which will stand Kafka on his head. Sort of a marvelous idea:

“Instead of having a guy who is more and more pursued and trapped and finally destroyed by his tormentors, I want to start with a guy tormented and then the opposite happens. They come to the jail and they open the door and they say to you, ‘A terrible mistake has been made.’ And they give you your suit back, with your glass and your wallet and your address book, and they apologize to you. And they say, ‘Look, people from big magazines are going to come and write stories on you. And here’s some money. And we’re very sorry about this.’ ”

[© Albert Goldman]

[Photo Credit: Louis Faurer via The Art Institute of Chicago]