New York City

For our forty-two years together, I have been assuring Helen Dudar that she ought to do a book. For forty-two years, she has assured me that she should not. My argument, reduced to its essence, is that she was and is one of the premier newspaper and magazine writers of our time—that the only thing separating her from the more notorious journalists of the day is her want of any talent at or will for self-promotion. Her argument, reduced to its essence, has been that that’s just a husband talking; books, to her, have always been Books!, the distant realm of artists like Jane Austen, say. or Virginia Woolf, and if your book isn’t good enough to share space on a shelf (or at least in a bookcase) with theirs, you have no business publishing one.

I’ve lost the argument, until now; this book, wrought without Dudar’s knowledge, is my clincher—a demonstration, by her own hand, that she is everything I’ve always claimed and more. Assembling it has been a stealth operation, in stolen moments at the office and in the midnight hours at home; apart from birthday and anniversary presents, it is the only important secret I’ve ever kept from my wife. The object has been to surprise her with a finished copy, and as I write these words, I have no idea how she will react to it. She may pop me upside the head with it. She may, on the other hand, concede that maybe, just maybe, I have been right all along.

What I do know is that the process has been a joy for me. I came to think of it as a long conversation with a writer of wit, grace, rigor, intellect and astonishing range, one capable of writing with equal authority about Johannes Vermeer or Jimmy Carter, Sigmund Freud or Malcolm X, the wonders of the Louvre or the arty little Bohemia resident in the Chelsea Hotel in New York. My side of the conversation consisted of an occasional. “God, that’s good,” or, more often, a silent smile. Nora Ephron has it right in her introduction: I wished way back then and still wish now that I could write as well as Helen Dudar always has—but, in our line of work, how many people can?

I knew Helen Dudar by her work long before I met her. Back in my newspapering days at the old St. Louis Globe-Democrat, some of us younger hands in the city room chipped in for a subscription to the New York Post. We did it mainly because that was where you could read the late, great columnist Murray Kempton, who was the writer we all hoped we would grow up to be. But as we browsed elsewhere through the paper, we discovered that there was a great deal more to it than Kempton’s luminous 800-word corner of a page in the opinion section.

The old Post had a loud, streety look, and the budget-grade ink of its tabloid headlines unfailingly came off on your hands. Appearances turned out to be deceiving; in those days before it fell into the hands of the down-market Australian press lord Rupert Murdoch, it was perhaps the only rival to the elegantly dying New York Herald Tribune as the best-written newspaper in America. Its staffers, sight unseen, became the familiars of my twenty-something fantasy life. and their names were as real and important to me as those of the poets, beats, ballplayers, gospel singers, civil-rights leaders and assorted outlaws of the spirit who also dwelt there.

A creation called “Helen Dudar” was one of them: she was, for me, an abstraction, a card with a name instead of a picture on one side and the evidence of her talent on the other. And then one morning in February 1960, I met her live in a corridor of the Suffolk County courthouse in Boston, where chance, in the form of a lurid murder trial, had brought us together. The Globe-Democrat had sent me because the victim and several other principals were from St. Louis; the Post had sent Dudar because the commute from New York was cheaper to Boston than to Los Angeles, where another, even juicier case was in progress at the same time.

On the first day of court, we were fleetingly introduced. I knew her name, she forgot mine. On day two or three, she missed a scrap of testimony and, during a break, approached me to see if I had it in my notes. “Hey, Saint Louis.” she said, blinding me with a smile. Her words hit me like a ’30s movie line, the kind of thing Rosalind Russell might have said in the pressroom classic His Girl Friday, which permitted me the fleeting illusion that I must be Cary Grant. I was smitten. It took Dudar a while longer, but we began dating during the trial, and a year and a half later, we were married.

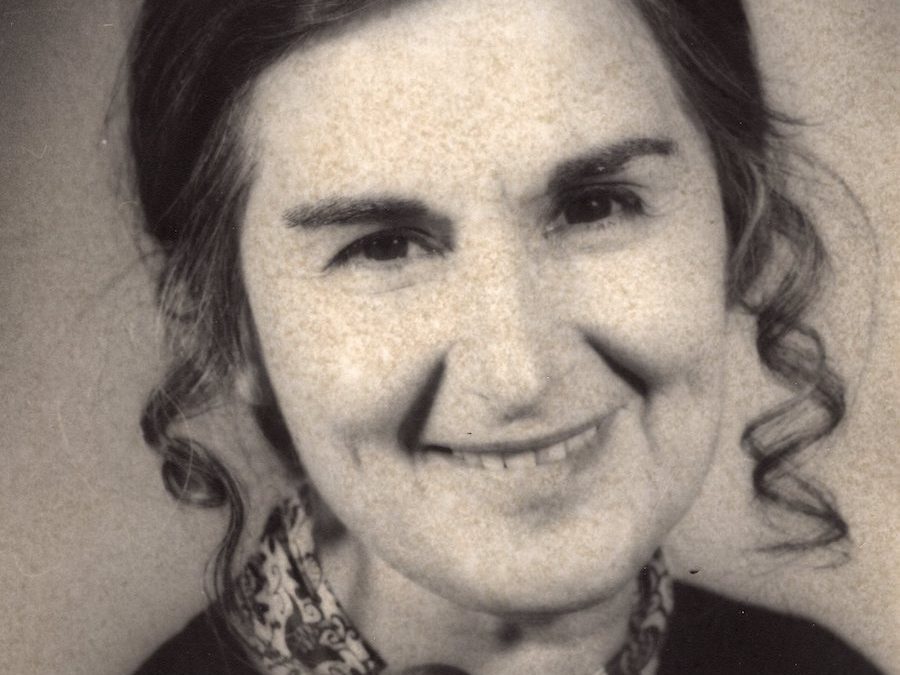

Helen Dudar and Peter Goldman, NYC, early 1970s.

Dudar by then had apprenticed at the brash young tabloid Newsday on Long Island, where she had grown up, and at a medical trade publication in New York, which had been her ticket to the big city. She had been tracked down there by a Post editor named Johnny Bott, who had noticed her work on the Island and remembered it favorably; he hired her for what would become a run of more than twenty years. During that time, she did a little (or, more accurately, a lot) of everything, which was what you did on a lean, cost-conscious paper like the Post. Like practically everybody else in the city room, she belonged to that tribe known in the business as general assignment reporters and rewritemen; “general assignment” meant that she was expected to write convincingly on short notice about movie stars, murderers, A-spies, Y-chromosomes, Democrats, Republicans, Shakespeareans, Shavians, two-headed babies, five-alarm fires, men of the moment and—an obligatory Saturday task at a paper ruled by a dowager publisher—the Woman of the Week.

And, of course, she covered trials. “Be a high-brow Dorothy Kilgallen,” Dudar’s editor told her, dispatching her to Boston for the trial at which we met. Kilgallen was one of the last of the great Sob Sisters, a trial reporter in the deep-purple Hearst tradition. Dudar painted in subtler hues, the gray of real life and the mauve of its ironies; her work on that Boston case won her one of the first three Meyer Berger Awards for distinguished reporting, a prize named for one of the grand masters of the craft. That trophy, like all her others, reposes somewhere in a closet in our apartment. The appreciation she valued more was that the Post kept sending her to the big ones, among them the trials of Bobby Kennedy’s murderer, Sirhan Sirhan, and of the kidnap-victim-turned-bank-robber-turned-penitent Patty Hearst.

It is both the secret and the fun of journalism, she likes to joke, that you get to be, briefly, the world’s foremost authority on the subject in front of you in the time available in which to explore it.

Dudar left the paper in the late 1970s and, except for a year on staff at the Daily News, has lived the free-lance life ever since. That life is a precarious one, subject to the shifting tastes of editors and to the whim of owners who hire and fire them and, occasionally, fold their publications under them. Dudar was, at various times, a regular in the arts-and-leisure section of The New York Times and on the leisure-and-arts page in The Wall Street Journal; a member of Writers Bloc, a journalists’ cooperative that produced pieces for newspapers across the country, and a contributor to, among others, Esquire, New York, Art in America, American Film, Saturday Review, Allure, The Nation, Connoisseur—and, most frequently and pleasurably over the past twenty years, Smithsonian.

Various publications have imposed various specialties on her; type-casting is an affliction not limited to show business. For The Times, most of her work had to do with theater and movies; for The Journal, books and authors; for Smithsonian, artists, collectors and museums. Dudar had little to no formal education in any of these subjects, but she approaches each of them as if she were a doctoral candidate preparing to defend her dissertation; it is both the secret and the fun of journalism, she likes to joke, that you get to be, briefly, the world’s foremost authority on the subject in front of you in the time available in which to explore it.

She was and is an old-school journalist in an era when the values and practices of popular journalism have been changing all around her—when newspapers and magazines have been shrinking or shutting down their libraries, and hence their institutional memories, as a needless extravagance; when preparation in depth for an assignment has often come to mean surfing the shallower waters of the World Wide Web; when fame is measured by how often you get on cable TV and superstardom is what happens when they make a movie with Robert Redford playing you; when style has steadily given way to the more easily struck postures of Attitude and when irony daily yields ground to something of coarser material called Edge.

Dudar thus remains a bit of a dinosaur in the Age of Buzz, where we in the trade live now. Still, as I was doing my digs into her writing, I was constantly reminded of things I had learned from four decades of watching her work—lessons that our younger sisters and brothers in a newer journalism might still profit from. Attitude may indeed be the game now, and Edge its most common weapon. What these pages affirm is that Edge and Attitude are as worthless as a four-flush in five-card stud if you don’t have anything behind it to back your play.

Dudar’s First Law, as I’ve already suggested, is meticulous homework; whether she had ten minutes on rewrite before the phones started ringing or a month to work a magazine profile of a painter or a politician, she has always used what time she had to read, look, think and rehearse her questions. If her subject was an artist. she would spend days at the library in the Frick Museum immersed in his or her life and works; if it was an author, she read or re-read not just the latest novel he or she was hawking but the entire oeuvre, or as much of it as deadlines allowed. Felicity in writing begins, as Virginia Woolf famously remarked, with rhythm, which is, like intelligence and irony, a gift of the gods. Dudar has those gifts, abundantly, but has never relied solely on them. Every precision-tooled word, every diamond-bright insight in these pages is written with the confidence that comes with knowing what you are talking about; in Dudar’s art, it only looks easy.

Like most journalists of the old school, she resisted the pronoun “I” except when it became necessary, and even then limited herself to cameo roles, often with a third-person pronoun as her disguise.

The further lesson for young journalists is actually to see what you are looking at. Calling this book The Attentive Eye is not simply a literary device; what Emerson wrote about an observant man in nature, seeing the world new every hour, seemed to me an apt description of Dudar’s journalism as well. Every new assignment for her is an occasion of anticipation and anxiety in roughly equal measure; together, they are the agents of an alchemy that gives so much of her work its startling freshness of sight and insight, even when her subject is some overexposed Somebody you thought you already knew.

Through Dudar’s attentive eye, we look past Peter O’Toole’s screen persona at a fidgety, Gauloise-smoking, pastille-popping wafer of a man “who can improvise an entire ballet without moving out of a Louis Seize chair.” We learn who carried Henry Kissinger’s dog’s pooper-scooper and why it matters to our understanding of him. We discover the modern master Robert Rauschenberg at home with the sources of his comfort (“a tall, iced glass of amber liquid”) and of his post-Pop inspiration (“a big television screen, muted and unwatched, and yet incessantly present”). Dudar’s work reminds us on every page of journalism as it existed before attitude became its preferred manner and celebrity its ambition. It is a journalism that begins on the ground and brings an unexpected way of seeing—and illuminating—whatever one encounters there. Attitude can be hatched in an office, at a computer keyboard. Reporters, as Dudar’s colleague Murray Kempton used to say, belong in the street, going around.

The pieces in this collection do not quite span all of Dudar’s half-century-plus in the trade; they are drawn instead from the years of our marriage, when I was privileged to be Dudar’s First Reader and she consented to being mine. We spent our newlywed year back in Saint Louis, and the earliest offering in these pages dates to that time—a martini-dry look at a local society pageant called the Veiled Prophet Ball. The story ran in a spunky little magazine called FOCUS/Midwest, now defunct, and created a small scandal in the city, where the annual spectacle of the rich at play was a pleasure much revered by the citizenry and the local press. The most recent is drawn, appropriately, from Smithsonian, which has been, de facto, Dudar’s home base in more recent times. It is a walk through a small, hidden gem of a museum called Hillwood in Washington and through the life and eccentricities of its late owner, a breakfast-cereal heiress who used to live there.

Those two, and their fifty companion pieces in this book, were selected in part because they are among the editor’s personal favorites and in part because they reflect the great breadth of Dudar’s interests and experience over the last half of the twentieth century and the dawning years of the twenty-first. Paul Cézanne crosses paths in these pages with John Updike and Betty Friedan; Dylan Thomas is discovered sleeping under the same roof as Janis Joplin, though in different beds and at different times; candidate Jimmy Carter smiles again, “a tireless, boyishly beamish smile,” and so, perhaps less expectedly, does Malcolm X, “a smile that could charm a cage of tigers into a pliable mass of purring pussycats.” Woody Allen is seen as a young stand-up comic, when movie-making was no more than an unseen gleam in his eye. Henry Kissinger and Nelson Rockefeller are glimpsed on the back slopes of state power, on their way down. Sigmund Freud puts in an appearance, not principally as the father of psychoanalysis but in his private life as a compulsive collector. Norman Mailer passes not principally as novelist and essayist but as a politician running quixotically for mayor of New York.

Eye is meant to be a browser’s book, and its contents are accordingly divided by subject matter among seven sections, to make browsing easier. A reader in search of writers will find them under “Wordsmiths;” artists are grouped as “Masters, Old & New;” politicians, moguls and a Watergate felon named John Ehrlichman appear as “The Mighty & the Fallen.” Some of the groupings are, I confess. a bit idiosyncratic; we find the outsider G. Legman, a scholar of erotica, side by side with the rebel Malcolm x in “Rebels & Outsiders;” George Bernard Shaw and Arthur Miller co-star with the performers in “Players,” and the Louvre shares acreage with the Chelsea Hotel among a selection of Worlds Apart.

Dudar herself appears everywhere. Like most journalists of the old school, she resisted the pronoun “I” except when it became necessary, and even then limited herself to cameo roles, often with a third-person pronoun as her disguise. But she offers us some irreverent peeks into her own store of minor vices in a section called “Tastemakers & Tastes,” and the last piece in the book—her cover story on the women’s movement for Newsweek—permits a deeper, more serious look into her own soul; the experience of immersing herself in the assignment was a transforming and liberating one for her—and, therefore, for me.

And now, if I may be permitted an aside to my wife, it’s past time for me to answer your long-ago movie line with a favorite of my own: Here’s looking at you, kid. This is your book, published with my love, at long last. I hope it brings you half the pleasure it has already brought me. And oh, by the way, don’t worry any more about whether it deserves to exist. You’ve lost that ancient argument; after several months of total immersion in your work, I’m confident that Austen and Woolf will not be embarrassed by your company.

[We will be featuring some of Dudar’s work in this space; in the meantime, do yourself a favor and check out The Attentive Eye.]