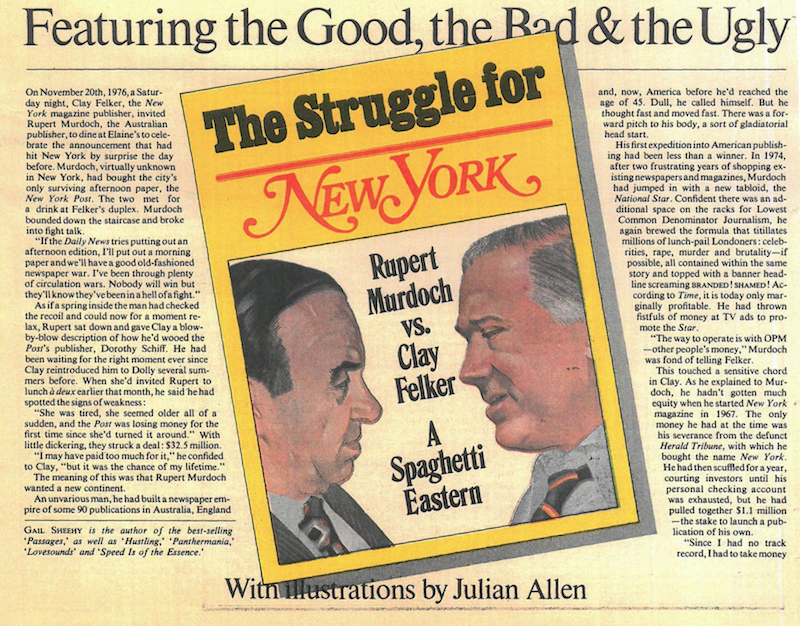

November 20th, 1976, a Saturday night, Clay Felker, the New York magazine publisher, invited Rupert Murdoch, the Australian publisher, to dine at Elaine’s to celebrate the announcement that had hit New York by surprise the day before. Murdoch, virtually unknown in New York, had bought the city’s only surviving afternoon paper, the New York Post. The two met for a drink at Felker’s duplex. Murdoch bounded down the staircase and broke into fight talk.

“If the Daily News tries putting out an afternoon edition, I’ll put out a morning paper and we’ll have a good old-fashioned newspaper war. I’ve been through plenty of circulation wars. Nobody will win but they’ll know they’ve been in a hell of a fight.”

As if a spring inside the man had checked the recoil and could now for a moment relax, Rupert sat down and gave Clay a blow-by-blow description of how he’d wooed the Post’s publisher, Dorothy Schiff. He had been waiting for the right moment ever since Clay reintroduced him to Dolly several summers before. When she’d invited Rupert to lunch à deux earlier that month, he said he had spotted the signs of weakness:

“She was tired, she seemed older all of a sudden, and the Post was losing money for the first time since she’d turned it around.” With little dickering, they struck a deal: $32.5 million.

“I may have paid too much for it,” he confided to Clay, “but it was the chance of my lifetime.”

The meaning of this was that Rupert Murdoch wanted a new continent.

An unvarious man, he had built a newspaper empire of some 90 publications in Australia, England and, now, America before he’d reached the age of 45. Dull, he called himself. But he thought fast and moved fast. There was a forward pitch to his body, a sort of gladiatorial head start.

His first expedition into American publishing had been less than a winner. In 1974, after two frustrating years of shopping existing newspapers and magazines, Murdoch had jumped in with a new tabloid, the National Star. Confident there was an additional space on the racks for Lowest Common Denominator Journalism, he again brewed the formula that titillates millions of lunch-pail Londoners: celebrities, rape, murder and brutality—if possible, all contained within the same story and topped with a banner headline screaming BRANDED! SHAMED! According to Time, it is today only marginally profitable. He had thrown fistfuls of money at TV ads to promote the Star.

“The way to operate is with OPM—other people’s money,” Murdoch was fond of telling Felker.

This touched a sensitive chord in Clay. As he explained to Murdoch, he hadn’t gotten much equity when he started New York magazine in 1967. The only money he had at the time was his severance from the defunct Herald Tribune, with which he bought the name New York. He had then scuffled for a year, courting investors until his personal checking account was exhausted, but he had pulled together $1.1 million—the stake to launch a publication of his own.

“Since I had no track record, I had to take money where I could get it,” Clay ruminated. “You can pay too much for money.”

Clay’s appetite for life was varied, romantic, unchecked. He had worked all his adult life at becoming a connoisseur of politics, art, Wall Street, Hollywood, antique silver, most everything. He devoured the histories of great events. Business nearly mesmerized him. He took classes in corporate accounting. Clay characterized himself as an “information sponge.”

Equally prodigious, perhaps, to his curiosity but far more dangerous was his emotional flammability. By striking the right surface, his detractors could turn Clay into an irrational dervish who would lash out at any and all constraints. Clay’s capacity for congeniality could be abruptly suspended by someone else’s dinner-party attack on any one of his writers, unleashing in him such a passionate defense as to torpedo polite conversation and leave hostesses in shock.

What attracted Felker and Murdoch to the same dinner table was a puzzlement. As different as they were in temperament, and even more so in the kinds of publications they represented, the biggest contrast between them was the scale on which they did business.

Murdoch’s empire was worth on the upside of $100 million and controlled by a family holding company, while Felker’s company had a market value somewhere between $10-$20 million and was controlled by other people’s money. Beneath the differences in numbers, though, ran a fascinating parallel in the bedrock of the two men’s careers.

Rupert’s father, Sir Keith Murdoch, the highly respected chief executive of a major newspaper chain, died an employee with little stock. He left his family two small newspapers in Adelaide, Australia. Sir Keith’s son had avenged that humiliating fall from status by pursuing, single-mindedly, a lifetime credo: 51% or nothing.

Clay Felker grew up in Webster Groves, Missouri, with a mother and father who were both working journalists. Carl Felker, his father, worked six and a half days a week as an editor of the Sporting News from 1925 to 1960. He came home Sunday afternoons and slept. It never occurred to him to ask for stock in the profitable newspaper company.

But all was not galloping down glory road for Rupert. Over the exultation of his first major conquest in the New World there hung a cloud of probable rejection in the Old World.

The relationship between Felker and Murdoch revolved more than anything around advice. That celebratory evening at Elaine’s, as was common, their conversation turned to sentences beginning with, “What you should do with the Voice…” or, “The one you should hire to find gossip for the Post…” Clay’s conversation was filled with the fizz of ideas for New West, New York’s eight-month-old California sibling. Whenever Clay mentioned the Village Voice, his only corporate acquisition, there was no mistaking the delight in his identification with the paper’s Peck’s bad boy irreverence. And that evening, as always, Clay spoke like a walking billboard for New York, his firstborn.

It was a festive dinner table at Elaine’s, with Felix Rohatyn1 giving Murdoch inside ironies from the board of Big Mac and Shirley MacLaine lecturing Murdoch on the political superiority of China and columnist Pete Hamill flattering him and Clay Felker enjoying the role of host to the newest curiosity in the Big Apple.

But all was not galloping down glory road for Rupert. Over the exultation of his first major conquest in the New World there hung a cloud of probable rejection in the Old World.

Murdoch’s ego ideal was Lord Thomson of Fleet. Like Murdoch, who came from down under as an Australian, Roy Thomson had come out of Canada—a “colonial.” But Thomson had broken the class barrier by fighting, buying and charming his way up to the point where he became proprietor of the London Times.

Longing to make the same leap, Murdoch had studied the minute details of Thomson’s career. Without question, the route to respectability was to buy a prestige publication in England. What had baffled Murdoch-watchers in London for some time was why, since he had gathered up considerable coin of the realm with the successful practice of low-rent journalism, Murdoch didn’t spend some of it on an “upmarket” publication. He never seemed to get around to it. Even as he imagined himself en route to becoming Lord Murdoch, he took one fatal turn. In 1973 one of his London papers caught British politician Lord Lambton with a prostitute and exposed him in photographs as a symbol of decadent British aristocracy.

It backfired. The establishment brutally ostracized Murdoch, which helped to drive him to sell his home in England and move lock, stock and silver chests to America.

Just this winter another chance arose in England. The venerable British institution, the Observer, was for sale. So excited was Murdoch about buying this newspaper that he and his wife took a new flat in Mayfair.

“Anna and I had gone over there earlier that week to savor the triumph of buying the Observer,” he told Clay at Elaine’s. “When I found out all of a sudden that Dolly was willing to sell the Post, I flew back.” That very night, in fact, Anna was in London, putting finishing touches on the new flat. If they would not take him politely, Murdoch was prepared to smash his way into the establishment.

I loved New York magazine. I wrote 50 stories for it. I believed in the reason for its conception, as Clay described it: “To serve the needs of the people who struggle to live and work in New York at this time in history, when there is the chaotic development of a new urban civilization.”

In the past 48 hours he’d had word his entree was being blocked. The journalists at the Observer refused to work if Murdoch took over. He was being invited out as a bidder by the newspaper’s board. In the background was the hand of the ruling class.

Clay commiserated with him. In the cab leaving Elaine’s it was Clay’s turn to confide that he was having problems with his board. “You’ve had a lot of experience with these things, Rupert. Maybe you can give me some advice.”

“Let’s get together and talk about it.”

Six weeks later Rupert Murdoch consummated the sneak takeover of New York magazine, its sister publication, New West, and the Village Voice, the small publishing company Clay Felker had been bragging about during the three years of their friendship.

Before going further, you should know the bias of the author. I have been “an item,” “a name most often linked with,” and a “frequent companion” of Clay Felker. In fact, we are very close and have been for seven years.

I loved New York magazine. I wrote 50 stories for it. I believed in the reason for its conception, as Clay described it: “To serve the needs of the people who struggle to live and work in New York at this time in history, when there is the chaotic development of a new urban civilization.” Clay Felker spotted this atomized class of urban survivors and created the forum that would redefine and catalyze them into a community of shared concerns. And because the magazine filled the need of a historical moment, it gave birth to a genre: at last count the cities of America had some 70 other magazines cast in precisely the mold created by Clay.

The social reward for those of us who worked on this cultural artifact was the feedback. It told us we existed, we had a use and a value. Each week the consequences of our work entered the culture, altered it, angered it, advised it, and every so often went off like a grenade. (In 1976 a member of a research group on the media sponsored by the Ford Foundation found that New York was the most common starting place for political ideas entering the culture.) We were a gaggle of individuals with distinct but differing points of view whose voices were enhanced by New York’s editors and artists, rather than homogenized into bland corporate journalism. The sense of family was strong. It was particularly precious to freelancers like myself, who are homeless by profession.

During the takeover fight I was in the trenches with the writers, in the midnight huddles with the lawyers, on the sidelines of the last meeting with the investors. To supplement this view I interviewed 32 people. In addition, calls were made to each stockholder whose name appeared as a seller to Murdoch on his filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The only person who refused to be interviewed was Rupert Murdoch.

Now you have my bias but not my question. Beyond setting the record straight, I see a larger question here: as more and more of American life is bureaucratized, conglomeratized, bred for passivity by television news and newspaper chains, does it matter if the personal passion still left in a few periodicals on the planet is squeezed out?

I. The Family Ties

They are always delicate and dangerous to define, those confluences of talent in print that occur from time to time and take on names like the Roundtable at the Algonquin or The Boys at Bleeck’s Bar. “The Boys” weren’t boys at all but men somewhere in their 30s who worked at the daily New York Herald Tribune and hung out at Bleeck’s drinking beer between deadlines.

One thing about working for the Herald Tribune, you could pretty well count on a strike for the summer. During one of those idle summers Clay Felker sat down with writer George W. Goodman and treasurer Win Maxwell and they worked out a budget for an independent magazine. Clay was already stuffing the Sunday Trib with a cultural tabloid he was editing called New York. But it didn’t belong to him.

In 1966, the losses of three major New York newspapers—the World-Telegram & Sun and the Journal-American along with the Herald Tribune—caused them to merge into a brief, ambiguous news soup known as the World Journal Tribune. Because it was so chaotic, Clay had time to experiment. With managing editor Jack Nessel at his side, all sorts of creative ingredients that later became standard fare in New York magazine were brewed in those ten anarchic months. This was when Tom Wolfe was given the freedom and encouragement to develop his idiosyncratic vision; he bounced ideas off Clay and turned out stories at a velocity he has never equaled since. Jimmy Breslin was perfecting the longform insult. George Goodman became “Adam Smith,” the wise guy Wall Street insider. Designers Milton Glaser and Jerome Snyder tried a presto-chango into food writers and invented “The Underground Gourmet,” while Clay was simultaneously launching Gael Greene as a haute cuisine food critic. “Best Bets” was originated as an illustrated tip sheet on what to do and buy in town each week. In fact the whole consumer information approach came into coherence there. A Save the Knish Foundation was started and buttons printed, the demand for which went on for weeks after the World Journal Tribune expired.

It was 1967. Felker was free, 41 years old, and the dream couldn’t have been clearer. The vision of an independent New York magazine came out of the electric impulses that traveled between Felker and art director Glaser, a neon bulb set in an art nouveau socket. Glaser had already established Pushpin Studio, one of the most successful design firms in the world. His peers working for ad agencies were earning $100,000 a year but Milton thrived on ideas he believed in, and New York was one of them. He devoted half his time to it for a salary of $25,000 in the first years. Just as important as his fluid imagination was his personal chemistry. Milton was the Jewish uncle, the guru with an easygoing giggle, the perfect grounding for Clay whose personality acted as the lightning rod of creativity and animosity.

And so they flew by the seat of their pants, these two.

Clay had been talking about a city magazine for years to Armand Erpf, a partner in the Wall Street investment firm of Loeb Rhoades who had always been intrigued by publishing. He became the financial architect of the company.

Armand liked the idea of maintaining a “creative tension” between the managers (Felker and Glaser) and the money men. Four of the initial investors brought in by Armand were appointed by him to the board of directors. One of them was a 32-year-old venture capitalist, Alan Patricof.

Patricof represented “other people’s money.” But, for him personally, the magazine held a certain je ne sais quoi that doesn’t spring to mind when one thinks about the meat distributing business, the railroad car identification business, the computer voice-response business or the animal feed supplement business, the major clients Alan Patricof attracted to his private investment company.

Apart from the glamour, the new magazine had great tax appeal: set up as a limited partnership, it allowed investors to write off almost their entire investment against personal income taxes. Patricof put in between $5000 and $10,000 of his own money, wrote it all off, and was later able to get for about 30¢ a share another block of 20,000 shares.

By late summer ’67 the core of the New York magazine family had been assembled. George Hirsch, then on the publishing staff at Life, was hastily hired to be publisher. Editorial staffers from that period recall Hirsch as the original rotten apple.

“Hirsch was in way over his head,” says Glaser. “He was a poseur. You’d go into his office and listen to this unending self-congratulatory drone. He could never get anybody to go to lunch with him. Not even his secretary.”

After a few weeks of working with Hirsch, both Felker and Glaser wanted to replace him. But Hirsch had found his protection in Alan Patricof, who insisted that Hirsch be kept on “because he’s just like me.”

This dispute easily took a back seat to the thrill of putting out a new magazine in the romantic slumminess of a low-rent brownstone on East 32nd Street. The roof leaked and people had to work in their coats in the winter, but it all added to the Left Bank atmosphere that kept everyone stimulated.

The elusive Tom Wolfe would come to the office late at night and spirit his piece away to rewrite it. Clay would chase Wolfe to his apartment to retrieve the piece before Wolfe turned off his phone. It was always worth it.

In Clay Felker the burning aspiration was to have a voice in his times and to run his own show.

A similar ritual held for Gloria Steinem. Every Tuesday night Clay sat around Gloria’s apartment waiting for her to finish her column. He was usually on line with one intellectual stage-door johnny or another, such as Ken Galbraith, who was waiting to take Gloria to dinner.

Late one morning when Breslin, Gloria and Clay were sitting around Limericks cafe they cooked up the idea that Norman Mailer should run for mayor. And why not Breslin for his running mate? Breslin fairly levitated at the idea. Scarcely taking notice of the fact he had lost, Breslin went on to write his first novel, The Gang that Couldn’t Shoot Straight, which Clay helped sell to the movies, and which brought Breslin the heady life of a best-selling author.

Long before the spring of 1975, when open warfare broke out between Patricof and Felker, they were in constant dispute over which of them would run the magazine.

In Clay Felker the burning aspiration was to have a voice in his times and to run his own show. He believed the former impossible without the latter and had therefore set out to learn the publishing business as well.

Raised in New York City, Alan Patricof had always been close enough to the parade of the talented and glamorous to know that he was not then, possibly not ever, going to be a natural part of it. Indeed, if there was anyone desperate to live the lifestyle Clay Felker represented, it was Alan Patricof.

Profit figured prominently in his reward system, but profit was far handier in rich dull companies than in the quixotic magazine business. It gradually became apparent that the primary reward Alan Patricof looked for in his association with New York magazine was prestige. “I wanted to be Clay’s friend,” he said often. He wanted to be introduced to the governor and the mayor and the big shots and the offbeats who came naturally to the parties of an editor. He yearned to be presented as the indispensable Patricof who minds the store for all the dreamers.

Beyond the contest of egos, the philosophies of Patricof and Felker on how to run a publishing business were in constant opposition. Felker wanted to plow profits back into operations in order to expand the business and, in the long run, the profits. Patricof, whose basic training had come in the go-go years of Wall Street, was fixated on maximizing short-term profits for the immediate effect of raising the price of the stock.

“Patricof, Towbin and Kempner absolutely never understood the publishing business,” recalls the company’s former chief financial officer, Ken Fadner. (He is talking about board members A. Robert Towbin, a partner in a small investment banking company; Thomas L. Kempner, a partner of Loeb Rhoades; and Patricof.) “I believe they didn’t even understand their own business: how to finance enterprises. At virtually every crucial juncture in the company’s development, these investment people gave very bad advice.

“The first was going public—in hindsight clearly a disaster. The company went public in 1969 to raise money it didn’t need. Two million dollars sat in low-income-producing fixed securities. New York magazine never touched a dollar of it. It was the classic maneuver from that whole gunslinging era of the Sixties which was totally discredited in the Seventies. This was Alan Patricof’s business. You invested in little companies, you got cheap stock, you stuck together two companies that had nothing to do with each other—like Tarrytown Conference Center and New York magazine—and you called them a ‘miniconglomerate.’ Then you took them public, and all the insiders would sell out and cash in on four or five times their investment.”

Says Felker: “Patricof seemed deeply to resent my role. He did raise a needed quarter of a million dollars at a very crucial moment, for which we rewarded him with the role of president of the company in an enthusiasm which we all lived to regret. Including Armand Erpf, who was getting ready to fire him just before he died.”

The winter ground was barely broken to receive Armand Erpf’s remains in 1971 when the contenders rushed into the power vacuum. Patricof joined forces with publisher George Hirsch and tried to oust Clay. Hirsch found a frontman in Jimmy Breslin, telling Breslin he was the heart and soul of the magazine, it couldn’t exist without him, and therefore he should have as much editorial control as Clay. Patricof meanwhile was urging Clay to turn over part of his stock to Breslin.

(The fact was, back in the magazine’s conception stage when paranoia was still locked away in Pandora’s box, Clay had set up a plan to spread stock ownership among key editorial people. Out of a total stock issue of 600,000 shares, Breslin got 10,000. Wolfe and “Adam Smith” also got 10,000 each but did not go along with the patricide idea, nor did smaller stockholders such as Steinem, which is to say that equity does not always corrupt.)

Hirsch and Breslin overplayed their hands. The entire board of directors concluded the company was on the way to destruction. They fired Hirsch. Breslin resigned. In the end, Patricof jumped to Clay’s side to save his own position.

But a climate of suspicion had been introduced between the financial directors and the editorial managers. It was the beginning of a fatal blight.

Families appear hermetic. And the New York magazine family—arrogant, unpredictable, barging along as the years passed like a wagon train with all the side flaps down—seemed immune to the jealousy and criticism it stirred up outside.

We were regularly accused, not always wrongfully, of being superficial and trendy. That’s show business. But we knew what was good.

Critics came to call the work of writers close to Clay “new journalism.” But there was no uniformity to the individual variations except that the stories were always arresting.

Tom Wolfe’s deadly accurate article, “Radical Chic,” will remain essential to an understanding of the history of the 1960s. The backlash of the silent majority against blacks was first revealed in Pete Hamill’s “The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class.” Women journalists found their earliest champion in Clay. In 1971 he joined with Gloria Steinem to launch Ms. magazine through a special issue of New York, and five years later contracted with Judith Daniels to give the same kind of send-off to her Savvy magazine. Andy Tobias cleverly executed the inside business stories Clay kept plowing into the magazine; Aaron Latham started his novel about the CIA inside New York’s covers; Richard Reeves’ cover story on Ford depicting the new president as Bozo the Clown first raised the stupidity issue around the world.

Critics came to call the work of writers close to Clay “new journalism.” But there was no uniformity to the individual variations except that the stories were always arresting. It had to do with what happened when good writers were given the confidence to cultivate their own truth. Clay usually didn’t care if he agreed or disagreed with them. He didn’t care if they were left or right or up or down. He encouraged skilled journalists to help themselves to other tools in the writing trade, including those once wielded exclusively by novelists: scene setting, narrative, dialogue, characterization, even stream of consciousness if it was appropriate.

Readers, however, were often irritated by finding so many contradictory dispositions within the same publication. “What are Felker’s politics?” they often asked. “Radical center,” he would usually say with an insecure smile, because he worried about having no fixed political ideology.

“That’s the best attribute you have,” he was repeatedly told by his partner Glaser, “the complete acceptance of ambiguity.”

Relations within the family weren’t always harmonious. The emotional circuitry was confusing. A new talent usually felt most comfortable looking to Clay as The Father and at herself or himself as The Favorite Child. Clay compounded the problem.

“I’ll make you a star,” was one of his more common openings. There would always be that blast of attention and affection in the first few weeks while Clay explored the new talent’s mind, creating the impression that one’s every response would be recorded indefinitely, and thought profound. Then one day (it came inevitably for everyone) he would walk past The Favorite Child’s desk and—blank. No hello, no recognition, nothing; he would simply stride by with his mind on an advertising lunch, a cover line, a Georgian silver biscuit box.

It was difficult for any single incipient star to see how Clay’s garden grew and why it needed constant recultivation. In the course of a year he dealt with easily over 100 writers. The secret was to give them a direction and then leave them alone. The careers of many of the major writers followed an inevitable progression from reporter to magazine writer to author. And once the author had the first hit book, it was not tempting to go back to the economics of peddling magazine stories. One memorable exception was Norman Mailer. While still an editor at Esquire Clay had spotted Mailer as a potential journalist, and by taking him to the 1960 Democratic convention he started America’s heir apparent to Hemingway on ten years of journalism, which many argue is among his finest work.

“At Esquire, at the Herald Tribune and then at New York, Clay helped to create the only truly self-supporting group of freelancers in the world,” says media analyst Edward Jay Epstein. He was forever beating the drum for his writers’ stories among his buddies in movieland or book publishing.

Things could turn very sour, however, if the talent didn’t stick around long enough to resolve this first blow to his or her vanity. When the temperature cooled in the bath of effulgence, what The Favorite Child often tried next was to defy Clay’s authority and get attention that way. They would clash. Clay would lose his legendary temper and turn into The Bully Father. In several such instances, the writers stomped off with unresolved feelings of rejection, which usually found their way into speech or print.

In 1974 Clay went to his board with a proposal to buy the Village Voice for cash. His main objective was to expand the company and give it a more stable economic base. The company had over $4 million in the bank and no debt. Chemical Bank was ready to finance the difference between that and the $5 million sale price of the Voice with a loan that would have been paid off in a year and a half.

“No, no, no,” the board insisted, “it’s not good for the company to borrow money.” Clay argued that it is the rule rather than the exception that a company has some debt in its capital base. The board wouldn’t budge. If Clay wanted the Voice badly enough, Patricof told him, he should “do a deal for stock.” Which is what eventually happened.

From Patricof’s point of view, the “crazy editor” stereotype was impenetrable. So was the curious loop in Patricof’s thinking by which he was persuaded that each time the company started a new venture, he was giving Clay something. “Eventually we gave him the Voice,” Patricof explains. “He used the opportunity to get a 50% salary increase. He didn’t deserve that kind of contract at that time because all we had done is take on an enormous responsibility to meet Clay’s desires.”

“Why was it giving?” Glaser demands. “What did we get? The opportunity to double our work load in order to build the company by two properties instead of one. They weren’t putting any money into it.”

When the Voice was married into New York against the protests of some Voice writers who, understandably, feared inbreeding would dilute their blood, the outside press fanned the discord.

In the end New York did not buy the Voice. They merged. The two controlling stockholders of the Voice, Carter Burden and Bartle Bull, received large bundles of stock in the newly expanded company. Chief financial officer Ken Fadner asserts that here was the second piece of bad advice contributed by the board:

“Sending Clay back to get a deal for stock caused his own equity to shrink, while Carter Burden and Bartle Bull came in with a combined control of 34%—by which they ultimately sold the company out.”

When the Voice was married into New York against the protests of some Voice writers who, understandably, feared inbreeding would dilute their blood, the outside press fanned the discord. Even as the criticism burned him, Clay’s attention to the Voice went up like a flare. And the Voice went right on promulgating its happy brand of cake-and-eat-it-too Marxism. In fact, it was Felker who chose the Voice to publish the suppressed Pike Committee Report on the CIA.

Rounding the new year into 1975, Patricof began courting the newest, presumably most naive but certainly most powerful speculator on the board: Carter Burden.

Burden had an erratic history. He came from Vanderbilt money and from California with its freeway of a value system, but he had tried to be taken seriously as a political reformer. In the same year Clay was raising money for his first magazine, Carter had gone to work for Robert Kennedy’s campaign at the Bedford-Stuyvesant committee. “Net, Carter did quite okay in that job,” says the former project director, Tom Johnston. But tension built up between workers, who resented him as an unqualified rich kid, and Burden, who resented being left out of meetings graced by the presence of Kennedy. “Nobody really meant to exclude Carter,” says Johnston, “but he kept asking, ‘Am I going to have a role?’ He wanted to know why I couldn’t arrange it. I just got exasperated.”

Carter often gave radical-chic parties at River House, a castlelike apartment house embracing a landscaped interior turnaround for limousines and a private pool and tennis courts, where the rich can isolate themselves from the realities of the city. Carter lived there with his exquisite Lalique figure of a wife, Amanda Mortimer, and he told Amanda that he thought he could be president someday. The murder of Robert Kennedy hit him doubly hard. “His whole career was Bobby,” Amanda said. “Then he had credentials. People would listen to him and know him by name.” Setting his sights on a City Council seat, Carter rented and subsequently bought a second apartment which he never occupied. It was uptown, on the tip of Fifth Avenue that touches Harlem, which qualified him to run in a weaker district. He won.

By the early 1970s, although he had built a faultlessly liberal voting record, the bottom seemed to be dropping out of both Carter’s personal life and his political vehicle. A very public affair carried on by his wife with Teddy Kennedy cut off his natural political alliance with the Kennedy family. His fairy-tale marriage broke up. In 1974, the year of his divorce, Carter Burden held the dubious distinction of having the single worst attendance record of any member of the City Council.

Patricof began working on Carter by setting up a private breakfast. “We’re going into ’75 and I’ll tell you, it’s disappointed me,” Patricof told Carter. “I really thought we’d be making a hell of a lot more money by now.”

Carter phoned Clay after the breakfast to report that Patricof was attacking his budgets behind his back. Nights like these Clay would have to go to a dumb John Wayne movie to calm down. The fact was that in 1975, a recession year, New York Magazine Company was holding its own compared to other publishing companies.

“Have you thought about replacing Patricof?” more than one of Clay’s advisers suggested. It was not within Clay’s power to hire or fire a chairman but he could propose a replacement—if he made an alliance with Burden. Could I get along with Carter as the chairman? Clay wondered.

Milton Glaser heard what Clay was about to do. Milton, whose personality is a natural lubricant, nearly went berserk.

“You’re out of your mind, Clay!” he warned. “Carter already has this big hunk of stock. Now you’re going to put him in a position of power? A weak man? The weak are precisely those you can’t control.”

As the months went on, Glaser formed a much clearer picture of Burden as a result of observing his basic mechanism for dealing with any yes or no situation. The mechanism was avoidance. Carter would not return anyone’s phone calls, not commit himself to anything. At the first hint of a potentially humiliating situation a shell would begin to crystallize around him. Any pressure at all, in fact, would start him rolling up into a ball and the ball wedging itself into a corner until there was no way at all of getting at it. The only thing one could do would be to bring down upon it some incredible, pulverizing force. Which of course was impossible, because no one had that much leverage. The armor was too rich.

At the last moment Clay decided against elevating Carter, but the reason was a breach of trust. Carter broke his word on signing the supplement to the shareholders’ agreement.

Patricof dates his alienation from Clay event by event; from the Voice purchase (because Clay turned to mergers expert Felix Rohatyn to negotiate, bypassing Patricof) to what he terms “Clay’s attempted overthrow of myself and Bob Towbin in spring ’75,” to winter 1975, when Clay asked Patricof to help get him a new contract (Clay was starting New West and believed he should be additionally compensated). And there was jealousy.

“I was just not going to stand by and be the quiet, nice guy anymore,” Patricof vowed. “I was only getting $12,000 a year for being named chairman,” he adds. (His only official duty was to preside over the annual meeting.) “And I never got a thing in ‘Best Bets.’ ”

Three or four times during our interview last February I asked him: “If being on the board brought you so much grief, rancor and humiliation, why didn’t you resign?”

“That’s a good question, Gail, that’s a good question,” he would say. Each time, he would shrug.

After two hours I suggested an answer: “Prestige?”

“Yes, prestige, I enjoyed the prestige. But I didn’t trade on it. When someone’s chairman of the board, they think that’s an important role. I’m not known in every restaurant. I don’t go to special screenings. I don’t use my press card….”

Measured by public acceptance, Clay Felker had achieved his dream. Measured by the balance sheets in 1976, the company had overall revenues of $26 million. New York magazine itself earned $1.2 million and the Village Voice earned $649,000 in pretax profits. But the pot of gold was going to be New West.

New West was a great romance. Clay fell in love with California, with its young, rawboned politics, its history and cultural heroes, its energy, cults, creeds and crazy variations on the American Dream.

“New West exceeded all our expectations in terms of circulation growth, advertising pages sold, popular acceptance,” Clay says, “and made us temporarily victims of our own success. It grew so rapidly that the costs outran the original budgets.”

At the same time New West was plunging into cost overruns, Clay was pressing for renegotiation of an employment contract. Discussions had started in the fall of 1975. Carter had continually delayed. Though pressing the subject at this point understandably raised the stress level on the board, Clay had his own reasons. Despite having built a company that was now a model in the publishing world, his equity was now confined to only ten percent of the value he had been able to create. He decided to live with that situation if the board would compensate him through salary or a share of the profits. Under his old contract he hadn’t had a raise or a bonus in a year and a half.

The board was unwilling to give him any increase in salary. It wasn’t until June 1976 that the board came back with an intricate proposal. “The first half gave me everything,” Clay says, “and clauses in the second half took it all away.”

Clay had a major decision to make. Should he spend the rest of his energies on a company that foreclosed the possibility of expanding his share of its success? Milton Glaser also felt trapped. He encouraged Clay to consider resigning.

Patricof, Burden and Bartle Bull were not what one would call natural allies. What they did have in common was experience in buying and selling people out, not excluding one another. Burden had negotiated the merger of the Voice behind the back of his best friend and former college roommate, Bartle Bull. Patricof had helped to fire Bull as publisher of the Voice. But it had come to be the summer of ’76 and Clay was insisting on settlement of his contract, and so the three sat down at a board meeting to shuffle the cards.

“Maybe we should sell him out to MCA,” Carter Burden reportedly said, “and watch Lew Wasserman chew him up.”

Many different budgets for New West had been batted around over the months before publication. The first time the board had actually approved a budget was in April, when the premiere issue came out. Clay forecast a maximum cumulative pretax loss of $4.1 million. The board approved.

In July, Clay informed the board that with the launch of a San Francisco edition and a stepped-up investment in circulation based on huge demand, the total loss before break-even would be $4.2 million. The board’s reaction was natural: how do we know this is the end?

When presenting this new forecast, Clay also announced that he and Milton would present a compromise proposal on their contracts at the next board meeting. The whole board would be required to vote on the compromise, and the clear implication was that if they didn’t vote yes, Clay and Milton would quit.

Carter panicked. This precipitated a dinner with Clay at which Jim Kelly, a Harvard-trained management consultant, was brought in to try to explain the economics of launching a magazine to Carter. He didn’t get it.

“I’m not sure our interests will ever be compatible,” he told Clay.

By August, Patricof was ready to move on a campaign to have Clay Felker tarred and fired. He arranged separate, clandestine meetings with each board member and pumped out the story that the company was in trouble because it had run out of cash. “I talked to everybody, whether it was breakfast or on the phone, including James Q. Wilson and Joan Glynn,” Patricof explains.2 “I asked them, ‘Do you think we’ve got a problem? What’s your attitude?’ Everybody seemed to be concerned but no one had a solution. So we just drifted on.”

Except for Patricof. “My own decision, to myself, was that the only solution was to find a buyer.”

“It’s very simple. We started with nothing and we have made something extraordinary.”

“The idea that we were in financial trouble is totally preposterous,” says Ken Fadner. “The board had voted unanimously to wipe out earnings to start New West, in order to allow the government to finance half of the costs. Patricof should know that better than anyone. It was he who recommended the board accept the internal financing plan Clay and I had formulated. They were simply using this as a lever over Clay so they wouldn’t have to give him a new contract. Burden’s philosophy was, ‘If l don’t get my dividends, Clay’s not getting his contract.’ And by denying his contract, the board gained power over Clay for the first time.”

A brawl broke out at the September ’76 board meeting.

“Clay, you just can’t focus on profits!” Patricof jabbed.

“You’ve forced through policies over the years, Alan, that have been disastrous in terms of the company’s ability to make money,” Clay shot back.

“If I’ve told you once I’ve told you 15 times, Clay, you don’t have to be a superstar all over town for paying writers well,” Patricof rallied. “I don’t know the successful magazine stories but I’m thinking of Oui and Penthouse and Playboy, which I’m told make a fortune.”

Milton Glaser delivered a clear, impassioned speech:

“It’s very simple. We started with nothing and we have made something extraordinary. Part of it was purely imagination applied to editorial product. Part of it was strategic business decisions. Opening up a magazine like New West is a business decision. And it was a brilliant move. You people wouldn’t have come to it. Clay and I figured out how to make the relationship between New York and New West work by sharing the family talents.”

Glaser looked around the room. “This has been a launch of unprecedented success,” he intoned, “and you guys are crying about the fact there’s little money in the bank. The fact is, we are at the healthiest point in the company’s whole existence.”

But egos had gone too far for healing. An executive committee was formed in an effort to give Burden more authority over the business. But first he had to learn it. Twenty-four sessions were held for Carter, with Felker and Fadner teaching. They never got beyond the first lesson, which was in circulation. Carter didn’t get it. At the end of the semester Carter submitted his bill for going to the executive committee school meetings—$8725.

”The lost opportunity was—1” Milton Glaser began the admission quietly in our interview and began again. “We weren’t wise enough to make that board of directors feel part of our community. They always felt on the outside. That guaranteed they would act only in their own financial interests, they would not have any family ties.”

II. The Conspiracy

Who could have guessed what unpredictable forces would come together in the same week of November 1976? Murdoch, recoiling from the humiliation at the hands of the British old boys, collides with Felker, who is wrestling with hostile directors over control of his own three American periodicals, ones for which Murdoch had been lying in wait for more than two years.

Ever since the spring of 1974 Murdoch had been waiting, since White Weld & Co., an investment-banking firm, called to tip him off that Carter Burden had gotten mostly stock—not cash—in the merger of the Village Voice, and would be looking to sell. Murdoch cultivated his friendship with Clay Felker, and his patience was rewarded.

On Monday, November 29th, Clay and Rupert had lunch.

“You and I could never work together,” he said to Clay out of the blue.

Clay agreed; they were both accustomed to running things.

The next thing Murdoch blurted was, “What you ought to do is borrow a lot of money in order to own something 51%. Then work your tail off for two years or three years, scrimp and save and pay off the thing, you’ll own it 100%, and then you don’t have to take any crap from anybody.”

“That’s right,” Clay nodded, “as theory.”

The next day Murdoch had his new investment banker, Stan Shuman of Allen and Company, call Patricof.

Patricof, it turned out, had been out shopping the deal around all fall. “Alan approached me to buy New York,” says Jack Yogman, who was in one of Patricof’s investment groups. “I didn’t even know it was available. I told him that I would not have anything to do with New York until I talked to Clay Felker.” Patricof also talked to Bob Guccione, publisher of Penthouse, and to representatives of the Pritzker fortune, which owns McCalls. Periodically he would call Carter to tempt him, or to sow seeds of mistrust about Clay. “It was Clay who spoke first to the Pritzkers about buying the company. It was initiated by one of [Clay’s] legal counsels, Paul Ziffren; I can tell you that for an absolute fact.” Ziffren states this is totally false, but Carter didn’t check such rumors with anybody but Patricof.

“Patricof would tell me that so-and-so had phoned him and I would say, ‘Well, I’m not interested in selling, but what did he have to say?’ ” Carter explains. “I was extremely ambivalent. I could never fish or cut bait.”

There was one person Carter refused to talk to about his stock: Clay. Since the beginning of summer Clay had been trying to get Carter to name a price for his shares so that he could make an offer. As Carter now explains, “I just did not respond to the question.”

When Patricof got the call from Shuman, however, he knew he had a live one. He gave Shuman the names of all the major stockholders and told him who was particularly unfriendly to Clay. “They didn’t trust Clay, he didn’t trust them, the same old story,” Murdoch recounted later. The conspiracy between the raider and the insiders had begun.

On the off chance that he might be able to buy the company with Felker’s cooperation, Murdoch called Clay in California. “I’ve been thinking about what we talked about,” he said, “and I have some ideas for you.” On December 9th, when Clay turned up in Murdoch’s Third Avenue office, he was startled to be introduced to Stan Shuman. He and Murdoch had a deal to offer.

Clay sat there while the two men talked about buying the company for five dollars a share, then spinning off New West to entice Clay into agreeing with the sale. Since New West seemed to Murdoch to be Clay’s favorite child, Murdoch offered to sell him back a third of it for a million dollars.

Stunned, Clay did what journalists always do. He asked questions. He left without giving a response. Two days later he called Murdoch to turn down the offer unequivocally. He also informed the board of the offer, the duty of any officer of a public company.

That weekend Clay flew home to Webster Groves, Missouri, to see his father who was slipping away in a blanket of minor strokes. Shaken, he returned on Sunday night to see his friend Felix Rohatyn, the wizard negotiator who concocted New York’s no-fault default. He told Felix he was concerned about the sudden increase in trading of New York Magazine Company (NYM Co.) stock and rise in the price. He was uneasy about Murdoch and suspicious that Towbin was making a market on insider information. He said he wanted somebody to buy out Burden.

Felix suggested Katharine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post. Felix said he would talk to her.

On the day of the New York magazine Christmas party, Friday, December 17th, lawyer Peter Tufo got through to his client, Carter Burden. He wanted authorization to talk hard figures with Murdoch.

“Consistent with my basic policy of ambivalence,” Carter explains, “I told Tufo, ‘Sure, you can listen to what they’re proposing.’ ”

That evening Tufo materialized beside Clay in the midst of the family’s Christmas party: “Do you want to work for Murdoch?”

“Of course not.” Clay laughed.

The Christmas party lasted five hours. During that time Tufo, Murdoch and Shuman had a leisurely dinner and sealed the family’s fate. Tufo gave them a price. Murdoch was keen: “We figured that at seven dollars a share, we’d preempt anyone else interested in acquiring NYM.”

By the account of one passive stockholder who sold, and who knew the other “old players” quite well, this is how Murdoch did the deed:

Between Christmas and New Year’s, Murdoch and his financial adviser were able to get oral understandings with the “old players”—Patricof, Towbin, the Loeb Rhoades interests managed by Thomas Kempner—that they all wanted to sell to Murdoch.

“What’s the price?” each of them asked.

“Whatever we gotta pay Carter,” was Shuman’s basic reply.

Not everyone else was bought, describes this stockholder, “but there were kind of oral agreements that ‘yes, we’re pissed off at Felker, and yes, we’d like the company to go to Murdoch if the price is right.’ ”

That meant that when the Murdoch forces faced Carter, they were able to tell him they already had oral understandings with enough people to take control of the company.

This is what is known as a “creeping tender offer.” In a declared tender offer, many state laws including New York and Delaware require a waiting period of at least 30 days before any stock can be purchased against the offer. Competitive bidders can come in, and it’s good news for stockholders because bidding wars keep putting more money into the pot. Instead, Murdoch moved secretly to lock up 51% of the stock, knowing that would halt any competitive bidding because no one would bid for minority interest.

With Peter Tufo acting as lawyer for Carter Burden throughout the month of December, the net effect was that Burden conducted a private bidding contest.

The only worry Carter had was getting around Clay’s right of first refusal. Tufo told him there was nothing to worry about. Tufo had drawn up that agreement. And Tufo knew about a loophole in it that no one else had noticed.

Clay’s friend David Frost worked hard to persuade him to take Christmas weekend off and fly down to Nassau to be his guest; he knew Clay was dangerously tired. Just before Christmas, Clay had been assured in a meeting with Kay Graham that the Washington Post was interested and would help. The first-refusal agreement with Burden allowed him 15 days to make a firm offer. Clay was relying on it.

The first formal notice of negotiations between Murdoch and Burden was given to company counsel Peter G. Schmidt (acting for Theodore Kheel who was out of the country) on Tuesday, December 28th. Clay heard about the offer for the first time the day before that, when Carter called him in Nassau. Clay told Carter, “I will buy your shares and Bartle Bull’s shares at seven dollars a share.” No response.

Schmidt began calling Tufo to determine if there was an active offer that required a report to the SEC. In each of their three conversations, Peter Schmidt would ask Tufo if there was an offer and what its terms were. In each conversation Tufo would change his story. The only consistency about Tufo was his refusal to talk through anybody’s squawk box. Presumably, Schmidt concluded, because he told everyone a different story. Schmidt made up his mind that if and when there was a suit, Peter Tufo should be named a defendant in the fraud.

“Get that yo-yo off the slopes!”

It is three o’clock on December 31st, the last afternoon of 1976, and Felix Rohatyn is fit to kill. Fortunately for Carter Burden, they are separated by 2000 miles. Felix is sitting in Newsweek’s Manhattan offices with Katharine Graham and her attorneys, who have been trying for two days with increasing desperation to buy NewYork Magazine Company, and with Clay Felker and Milton Glaser and their attorneys, who have been trying with mounting agitation to sell it to her. Carter is somewhere in that luxury Idaho crater called Sun Valley. On the other end of the telephone is Peter Tufo, who has been saying all day long that he couldn’t reach Carter because his client is on the slopes.

“Peter,” says Felix, “there is no snow on the slopes. Stop bullshitting me.”

“You’re just going to have to give me more time,” Tufo says.

“We’ll give you till four,” Felix says darkly.

The humiliation level in the room rises considerably during the next hour and three-quarters. Katharine Graham, queen mother of one of the most highly respected publishing organizations in the world, has been waiting for two days for the phone to ring. It doesn’t. Carter Burden is treating her like a jilted dance-hall dolly.

At 4:45 Tufo calls back and tells Felix, “Look, I’ve talked to Carter, and it cannot go your way.”

“You mean it can’t go our way at any price?” Felix asks in astonishment.

“I can’t tell you more than that,” says Tufo.

Felix says he will extend the deadline until 5:30.

The people in the room cannot believe what they are hearing. They have been working around the clock to prevent the great magazine raid. The events of the past two weeks swim in their heads.

On Thursday, December 30th, the Washington Post had been all ready to go. “They suggested I call Peter Tufo,” said Felix Rohatyn, “on the theory that since I’m an important New York citizen, Tufo would be less likely to welsh on me than on the others.”

Felix is not the star mergers-and-acquisition specialist at Lazard Frères for nothing. He had chosen his words for Tufo scrupulously.

“Peter, I’m here with Kay Graham and Clay Felker and Milton Glaser and I am acting in my capacity as investment banker to the Washington Post. I understand that you have offered Carter’s stock to Clay until tomorrow noon, at seven dollars a share, under a first-refusal agreement. I want you to know that Clay will buy that stock, at seven dollars a share, and that the Washington Post is financing it. I understand that there are two other conditions. One is that the same offer be made to all the shareholders. I’m telling you that the Washington Post will make that same offer. Second, that Carter be indemnified against that commitment not being followed through, and you have our word on that. I assume since that’s it,” Felix said, “we have a deal.”

Tufo hemmed and hawed a bit, but the clear implication to Felix and to all seven of the others sitting in the Newsweek office was they had a deal.

“We’ve got a whole bunch of high-priced lawyers sitting around here,” Felix added with good humor, “why don’t I just send them over to your office with a check and we’ll draw the agreements right now?”

“Why don’t we wait and do it first thing in the morning,” Tufo said. He gave no reason.

Clay had gone off in relatively good spirits to have dinner with Dick Reeves and Kay Graham. Felix had gone to his hotel to pick up his kids for dinner. Tufo’s return call caught him going out the door: “Look, I ought to tell you that there is another condition here that I wasn’t able to discuss on the telephone—Carter’s role. The competition is going to give Carter a title and a salary, $24,000 a year. How would you feel about that?”

The disdain in Felix Rohatyn’s voice was undisguised. “If you’re looking for a tip, as long as we disclose it to the world I think it can probably be worked out. But even if they wanted to give Carter a title, the fact of life is that there wouldn’t be a role for him. There won’t be a role with Murdoch either.”

Tufo said that could be a real problem.

“Look, Peter,” said the exasperated Felix, “we have a deal. I told you we have a deal, our lawyers will be at your office tomorrow morning at nine.”

Clay had been deep in a troubled sleep when the phone rang at 1:30 in the morning. The familiar voice of a heavily drawing pipe smoker began talking.

“You said you didn’t want to work for the Washington Post,” Carter Burden said.

“I don’t want to work for anybody, but I’ve had to do this because you were slamming the door on my ability to make a deal,” Clay Felker said.

Carter complained, “There won’t be any role for me with the Washington Post.”

“No.”

“Well, Murdoch is offering me a role.”

“There isn’t going to be a role with Murdoch either. There won’t even be any magazine after a while, with Murdoch.”

“Well,” said Carter Burden, “I’m not going to sell to you.” “Look, Tufo made a verbal agreement and verbal agreements are binding,” Clay Felker said. “If you go through with this and destroy these publications, it will be a permanent stain on your reputation.”

Clay had not taken the bait, not blown up, but he couldn’t sleep the rest of the night. Carter had obviously called to provoke a fight and give himself an out. That Clay Felker had this time restrained his temper would never be believed—it would be the little boy who cried wolf.

The next morning, December 31st, Felix had a troubled call from Mrs. Graham. She reported receiving a threatening call telling her she would never be able to buy the company. Felix said, “This thing could turn very nasty. Regardless of the first-refusal agreement, these people are not going to live by it.” It was agreed that Felix should go immediately to Tufo’s office with a check in his pocket.

“Kay left the price pretty much up to me,” Felix says. “I decided I would offer him $7.50 on the theory that if Burden wanted to do the right thing, but simply wanted his greed met, he would come back with a somewhat higher price and we would meet it.”

Tufo received Felix but would not receive a proposal or a check. He wasn’t sure he could get an answer from Carter that quickly, he said.

“Burden has been screwing around with this thing for months,” Felix said, “of course he can make up his mind.”

Felix was sent away. What Felix didn’t know was that Carter Burden’s agreement to sell to Murdoch had already been prepared. The amount typed in was Murdoch’s original price of seven dollars a share. And Bartle Bull’s sale agreement had already been signed.

And so here in the Newsweek offices in the last dying hours of 1976, the air of unreality is stifling. At 8 p.m. Katharine Graham takes the phone with its last feeble connection to Peter Tufo and she implores, “What is it you really want? Should I fly out to see Carter? I’ll do anything.”

“Kay, don’t,” Felix whispers, “it’s demeaning to you. The whole thing is obscene. At least keep your dignity.”

“Is there anything humanly possible?” Katharine Graham pleads.

Stan Shuman was at that moment near arrival from vacation in Florida and ready with a chartered plane. He picked up Peter Tufo and Princess Lee Radziwill and the trio flew to Murdoch’s colonial farmhouse in upstate New York. In the early hours of 1977 the Murdoch forces were speeding by private jet to Sun Valley, Idaho, to start the New Year by sewing up Carter Burden.

III The Family Powwow

On the first morning of the New Year, Clay Felker awoke inside the body of a fallen man from whom he felt peculiarly detached. Propelled into a role that he didn’t understand, he watched this disembodied character pick himself up, splash water on his slugged face, climb into the saddle of his Exercycle and ride for a hard hour until his juices began running and he was ready to do what he had to do.

“Let’s go for the TRO,” he told his lawyer on the phone.

Reginald Leo Duff, attorney at law, headed to the federal courthouse to find a judge who would grant a temporary restraining order, enjoining the sale of Carter Burden’s stock. Late in the day Duff found Judge Thomas P. Griesa in his Upper East Side apartment, sitting by his harpsichord. The judge granted the order. The fight was on.

These were the stakes: control of a company which in 1976 had revenues of $26 million. Carter Burden owned 24% of the stock. Clay Felker owned ten percent. To prevent Burden from selling his shares, the single largest block, to an unacceptable third party, a shareholder’s agreement had been signed during the 1974 Voice merger that gave Felker the “right of first refusal,” i.e., the right to match any offer by a third party. The lawsuit sought to block Burden permanently from selling to Murdoch on the basis that he and his lawyer Tufo, by refusing to accept Felker’s $7.50 offer backed by the Washington Post Company, had defrauded Felker of his right of first refusal.

Also at stake—for Felker—was personal freedom. One of the assets of the company was Felker’s employment contract which contained a noncompete clause, so broadly drawn that if Felker stopped working for New York Magazine Company it would have prohibited him from being an officer, director, manager, employee, editor, shareholder, partner or consultant to any person or magazine in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut or California, or to a publication in any other state which had over 50% of its circulation outside the state where it was published.

Overnight, three packs of urban cowboys were headed for a showdown—the business boys, the journalists and the lawmen. The members of each clan, thinking of themselves as sophisticates, rode into the clash, saw into one another’s minds and were shocked at how different were their values and vanities, their conduct and codes.

The journalists mounted their high horses and issued statements that served only to immortalize gaps of ignorance in their understanding of how society works. We thought ourselves so sharp, but as the next ten days were played, we realized that we were in fact a clan of fuzzy-headed romantics. But we also broke out of the cynicism and sense of helplessness that commonly says: the individual is not responsible, we don’t have to worry about quitting, all bosses are alike. “No!” we said. “This is wrong and we’re going to stand up.”

The finance gang closed ranks more easily, having been schooled early in the ethics traditionally respected by business boys everywhere. It is an exploitation ethic: “If I can screw you, I will. But don’t take it personally for God’s sake! It’s a game of wits—no hard feelings—and the fittest survive.”

The lawmen, in the end, had a greater hand in the outcome than any of the rest. They had designed the original agreements, and where battles over money and power are joined, the results almost always come down to who signed or didn’t sign what piece of paper.

Clay’s and Milton’s vanity was to think that if high noon ever came, even as the raider was riding into town, their board would ultimately decide that they were indispensable and cover them. But the duo had not fully reckoned the penalty for their injury to the finance boys whom they had kept out of the family. Nor had they been dispassionate enough to foresee how, because of their own success, they could have expected, at some point, to be devoured. Big corporations rarely start things. They wait for individuals to create a “viable” asset out of years of creativity and risk. When it is mature and profitable, the big corporation comes along and swallows it.

There were those who sensed it was all over the moment Murdoch got word that he was to be the cover subject of the two largest newsweeklies on the planet. “I wonder if we’re not just baiting the trap,” ruminated a reporter at Newsweek during the second week of January while her magazine readied the story. She was wrestling with one of the central dilemmas of mass journalism: how to cover the news without becoming a handmaiden to making it. For in America the true status, the certification that in the most contemporary sense one’s class position is secure, the pop peerage coveted by punk terrorists and proper businessmen alike is to be able to say: I am a celebrity!

“Clay has been very good to me. I think of him as my brother—and sometimes he may be wrong—but I’ve always felt I needed Clay. I also felt I could do something for him in return. That’s why the passion is so enormous. I want to save my brother.”

Two New York writers were especially caught up in the thrill of actually “making developments.” Dick Reeves and Ken Auletta (political reporters, distinguished and up-and-coming, respectively) started out that first Saturday and Sunday of siege week—January 1st through 7th, 1977—doing much more than reporting back to the family. They were in direct touch with the key board members—Patricof, Towbin and Kempner. They wondered why they hadn’t been called in to placate the board before. To them, the business boys sounded positively star-struck! Indeed, fans!

“Fools, you’re fools!” Byron Dobell told the writers each time they called in to report on one conversation or another in which Towbin assured them the board would “love to” meet with the writers to resolve this thing, vouchsafing that he would urge no action be taken until the board meeting the following Tuesday. Reeves and Auletta also described conversations with Kempner in which he kept referring to them as “the most distinguished journalists in America” and spoke of what “an honor” it would be to meet with them.

“We’ve got to issue a strong statement right now or this company is going to be pirated right out from under us,” Byron warned.

“Why insult these people in public, Byron?” Reeves argued. “They want to talk to us.”

“You’re talking to the enemy,” Byron shouted into the phone. “These people are in on it!” Byron was histrionic. They began to think he was losing his grip.

“Adam Smith” rang Towbin from the Bahamas (his reward was a $95 phone bill) trying to get to the bottom of rumors about the sale to Murdoch. “Look, nothing’s going to happen,” Towbin told him.

It went on like that with the writers and editors all weekend until the first piece of hard news came in late Sunday afternoon, January 2nd. Even as Towbin was soothing Auletta by phone, Felix Rohatyn called to notify management that Patricof and Kempner had just sold. Together with Towbin and others yet unknown, they were on their way to a gala 8 p.m. signing party at Murdoch’s Fifth Avenue apartment.

Over that weekend the business boys learned how easy it is to play the narcissism of journalists. And the journalists learned a phrase which helped them to understand the business boys: “On Wall Street, loyalty is a quarter of a point.”

For the writers, siege week began with a family huddle at 8 a.m. Monday, January 3rd, at New York’s Second Avenue offices. There was an urgent pinch to their faces; even Aaron Latham, who has the detachment of a ponderosa pine, looked jumpy. Since Clay and Milton were locked up in lawyers’ offices indefinitely, that created a need for the absurd formality of reading a prepared statement from Clay.

“Despite recent developments,” the statement read, “I intend to fight and fight as hard as I can to keep what we have all built from being damaged. And I expect to win….”

A summit conference of sorts was called in the office dining room. Jack Newfield and Marianne Partridge had come up from the Voice. Frank Lalli, who happened to be in town, represented New West.

New York’s managing editor, Byron Dobell, was looking flushed and triumphant. I heard Reeves whisper to Auletta, “How old is Byron? That extra ten years must have something to do with sharpening judgment. I’ve heard enough politicians lie, but nothing like those lying sons of bitches on the board. Byron was right on the nose.”

In the first half-hour we arrived at a definition of ourselves. We were a “talent package.” We were not up for “barter.” And we meant to demand our right to “protect the company from deterioration.” Our support was behind the editorial leadership that had brought us all together.

Steve Brill, a young staff writer out of Yale Law School, and I were asked to draft a statement for a noon press conference.

In the momentum of action, it is probably safe to say that none of us focused on the precedent being set here: a non-unionized group of employees was ready to pull a job action not to fatten their own paychecks but to save the spirit of the company.

The entire staff of the magazine was called in, 125 people. The room filled with the faces of uncertain secretaries, underpaid staff regulars, people who had medical bills, mortgages and ailing parents to worry about and who did not think of themselves as “stars.” A great deal was made over the fact that no pressure would be put on anyone to stop work. Freelancers obviously had other irons in the fire; it wasn’t fair to ask people in the mail room or even the ad department to stick their necks out. If and when the moment came, it would be each person to his or her decision.

All this did was insult people’s loyalty. The mail room people, advertising people, clerical newcomers, switchboard operators, all wanted to be given the chance to act as few of us ever have the opportunity to—on principle.

By noon we had closed ranks around a clear consensus. It startled many of us to discover how intimately our sense of self-worth was tied to New York, New West or the Voice. All at once we were a unit under siege, a unit that immediately sensed its perimeters.

We met the press but not as pals, not even as colleagues. Everyone outside our perimeter was now a potential enemy. From the moment we turned into activists we also grasped a reality that continually eluded our brethren. What bound this bunch together was too emotional to be expressed. Phrases like “editorial integrity” and “creative community” stuck to the roof of the mouth with their piousness. It was hard to express our real feelings, they were so embarrassing—loyalty, self-respect, love.

Byron alone was willing to put it on a personal level. “Clay has been very good to me. I think of him as my brother—and sometimes he may be wrong—but I’ve always felt I needed Clay. I also felt I could do something for him in return. That’s why the passion is so enormous. I want to save my brother.”

But other staff members shut him up. “Byron, the TV cameras don’t want to hear that.”

“You’re probably right,” he said.

This first news conference started a press hysteria. For the next two weeks the media would be saturated with the story. Some reporters saw the real point but chose to ignore it. Others had no idea of what we were talking about, themselves having become interchangeable drawers in one of the journalistic bureaucracies. It was covered like the Super Bowl of publishing.

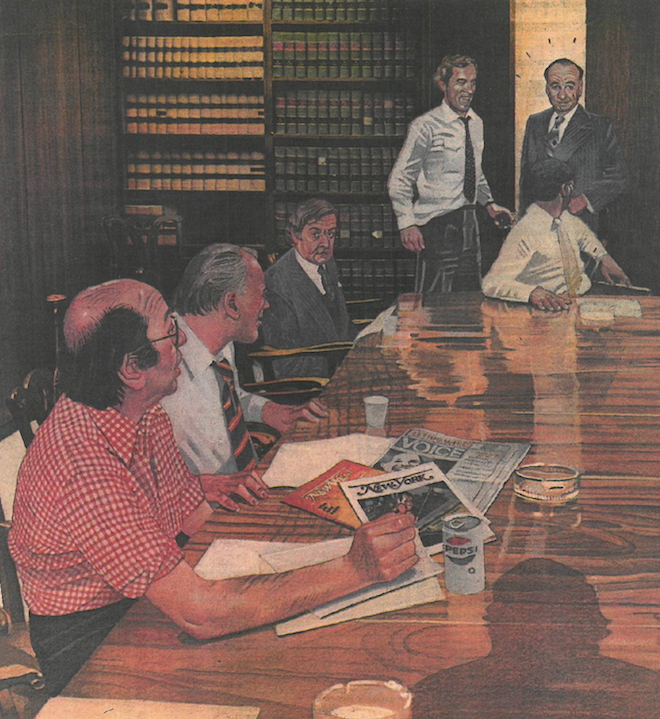

The decisive board meeting was set for 7 p.m. that evening. The writers’ delegation was jumpy. We were ignorant about the law of takeovers and the rights of employees. Attorney Martin Lipton, a wizard of tender-offer law, agreed to give us advice, gratis.

Lipton told us to look into violations of the New York State Takeover Act, Delaware State Takeover Act, SEC violations, antitrust violations; in fact, the very board meeting we were facing might well be declared illegal because the people who sold their stock had already disqualified themselves as voting directors.

The rumor reached us at Lipton’s office that the sellouts had a lynching party waiting. We hurried out of one law firm and raced up Park Avenue to another law firm where the board of directors were about to meet. Coming into the reception area, it was impossible not to feel the suspense of walking into OK Corral.

IV. The Shoot-Out

“Clay’s in the back,” someone says.

We are escorted to a holding room. The writers’ delegation is to hold tight in a small, white, sensory-deprivation chamber, to wait to see if the directors will hear us. Labor negotiator Ted Kheel, whose offices these are, sends in a half-gallon of Chivas Regal.

Clay and Milton enter the board room. The atmosphere is leaden. Carter Burden is chewing beaverishly on his pipe. Bob Towbin’s shirt is already blousing out. Alan Patricof’s agitation is showing in the twitching of every nerve ending. Clay and Milton nod imperceptibly at the seven others at the table and sit down. Kheel has arranged for a court stenographer: if there are to be any ambushes, the company counsel wants it on the record. The only person who seems no different is Tom Kempner. That does not surprise Glaser. He thinks of Kempner as constitutionally unconscious. A man who inherited millions and plays tennis, Kempner regularly drops into a snoring sleep for two-thirds of every board meeting.

Before the board meeting starts, Gordon Davis, a Burden appointee, calls for a recess and goes into the bathroom with Peter Tufo, Burden’s lawyer. Tufo comes out asking for a copy of the bylaws. Patricof takes one into the bathroom. Their mysterious moves continue for three-quarters of an hour. The others sit in the windowless board room, exuding deep tension and awkwardness.

Patricof calls the meeting to order. “A court stenographer is inappropriate,” he says, and calls for a vote that sends the stenographer packing. Kheel, who is known for his skill in negotiating highly charged conflicts, protests. He is ignored.

In the holding room the restlessness is already getting to Reeves, Auletta and Brill. They dance into the bathroom in their adrenalized state. In the middle of a joke they head, boom, through the door—and who do they flush out? Murdoch! The enigmatic man they have seen only in the newspapers is sitting on the sink, briefing Towbin. Next to Murdoch is his man Shuman. The East Side lavatory freezes. For a beat, the six faces register the absurdity of the situation with wan half-smiles. Then Murdoch and party turn on their heels and soundlessly vanish.

Murdoch says nothing. He is singularly calm. He takes one of the empty directors’ chairs. There is an economy about the man in every way.

This is beginning to look like the first board meeting on record to take place in the can.

Murdoch walks to the reception area to speak to the press. He stands with one hand in the pocket of his black suit, his voice utterly composed.

“I quite understand why there would be some nervousness on the part of the staff. It’s natural to be concerned about their jobs with a new owner….”

“He can’t conceive of people acting on principle,” Auletta fumes to Reeves, both of whom have been listening to Murdoch’s statement, “and neither can most of the bunch in that room, because in their world people act on dollars.”

Back in the board room, two more unsuspecting participants are felled by the next salvo. Chairman Patricof moves that directors Joan Glynn and James Wilson be “removed without cause.”

Felker and Glaser are astonished. Joan Glynn, a towering figure in her own board room, former president of Simplicity Patterns and now head of Revlon’s Borghese division, being booted out? Professor James Q. Wilson, holder of the Shattuck chair in government at Harvard, the man who helped calm the madness of student revolt, the national expert on police behavior—it is unthinkable. But the two shaken figures hurry out, are fed to the press, escape into an elevator.

Inside, Kheel is jumping out of his chair. “On the advice of your counsel I am telling you that action is illegal!”

Alan Patricof rolls right over Kheel and goes on making his mysterious, but quite methodical, moves.

“Now, Alan?” Bartle Bull is standing at the board room door in a fever of anticipation.

“No, no, not yet.”

Patricof fires again. This time the target is Kheel. Burden, Bull, Tufo, Towbin, Kempner and Patricof, with Gordon Davis abstaining—vote to remove Kheel as company counsel.

Kheel leaps up in outrage. He’ll sue them all! The battle rages until the conspirators grow impatient. The element of surprise is important in their showdown strategy.

“Now, Alan?” Bull asks urgently. He keeps opening the door a crack. The trail of impatience clearly runs past Bull to some unspecified presence outside.

“Wait a second, just one more second,” Patricof answers in a stage whisper. “I have to make a proposal first.” He clears his throat and announces ceremoniously, “I now propose that we put two new members on the board—”

The roustabout opens the cage door—and yes! Into the center springs Murdoch! Followed by his money changer, the bulky figure of Stan Shuman.

Milton and Clay are incredulous. It is like watching an accident in a dream: one is aware but without will.

Murdoch says nothing. He is singularly calm. He takes one of the empty directors’ chairs. There is an economy about the man in every way. Proxies are passed around by his man Shuman. The claim is made that subject to release of the Burden shares at dispute in the lawsuit, Murdoch has acquired 51%.

Clay and Milton dazedly turn over the proxies in their hands. George A. Hirsch; Alan J. Patricof; Arthur Ross—the name clicks: Patricof’s old boss; A. Robert Towbin and another paper in which he speaks for the money of company clients; John Loeb, the head of Loeb, Rhoades3; another Loeb family foundation and trust secured by the signature of Thomas Kempner; and Edgar Bronfman.

These unexpected blows are too bizarre to register in Clay’s and Milton’s rational minds. But somewhere deep inside both men an unknown territory has been deadened.

An hour and a half have passed since the board convened. In the writers’ room we remain in the dark. Holding a bunch of journalists in an information vacuum is like shaking a bottle of seltzer and holding a finger over the top. At last, the hyperexcited figure of Reginald Leo Duff rushes in to see us. “It’s terrific!” the attorney squeals. “It’s just—what a legal case we have!”

Duff gives a blow-by-blow account of the board room carnage: “They” have thrown Kheel out as corporate counsel; two Felker directors have been kicked out; Rupert Murdoch and his banker have the Wilson and Glynn seats; Clay and Milton have just had their balls crushed; and “they”—by some arcane maneuver—have dissolved the board meeting altogether and are holding a stockholders’ meeting. Blood is running in the halls, but our lawyer is gleeful. Events are becoming deranged.

Milton staggers into our room. He is barely coherent. He has asked Patricof several times to receive the writers; no answer. At 8:05 Ken Auletta picks up the phone. He dials New York state’s attorney general, Louis Lefkowitz, at home, hoping to initiate an investigation. Patricof walks by and darts in. “Ken, don’t be upset. You have to understand.”

“Hello Mr. Attorney General,” Auletta says into the phone.

A spasm shakes Patricof. He walks away twitching like a marionette. Five minutes later he is back.

“We’ll take the writers now,” Patricof announces. “Do there have to be so many?”

Five people rise. As our small band of irregulars files out, I smile and give them names: the counsel, the revolutionary, the star, the campaign manager, the clown.

The body-heated board room is in the mid-80s by the time they are admitted. Everyone is in shirt sleeves. Except Murdoch. Everyone speaks heatedly. Except Murdoch.

Byron Dobell is the keynote speaker. “I don’t know you people,” Dobell says fervently, “and I don’t want to know you. But I do know you people have been living off Clay Felker’s genius for eight years. Going to your cocktail parties and pretending you had something to do with building this product.”