You smell hot dogs and beer. You feel the anticipation. Men sport bright caps with fancy insignias. Women wear shiny team jackets two sizes too large. Kids struggle with long leather mitts. They hand over their tickets and enter the arena and start to search, not for a seat, but for history, for second-hand iconography, for dusty slices of immortality, for Number 7.

The Baseball Memorabilia Show has converted the fourth floor of the Claridge Hotel and Casino in AC into an American archeological dig. Antiquarians from California and Florida and most place in between are here to unearth rare fossils and sentimental artifacts. Walls are lined with the hieroglyphics of the sport: pennants and posters. Tables are stacked with faded baseball cards and assorted souvenirs, a Philadelphia A’s ashtray, a Pete Rose parka. Living relics, Whitey Ford and Duke Snider and Billy Martin, are here for atmosphere, an occasional autograph and to have their memories tested by fans who possess baseball encyclopedias for brains.

It doesn’t take long to realize that the greatest number and most treasured antiques revolved around one particular player. His face is everywhere, his signature on everything. His is the King Tut of Hardball. He is down the long hall now, in a private room, confronted by an endless stream of supplicants.

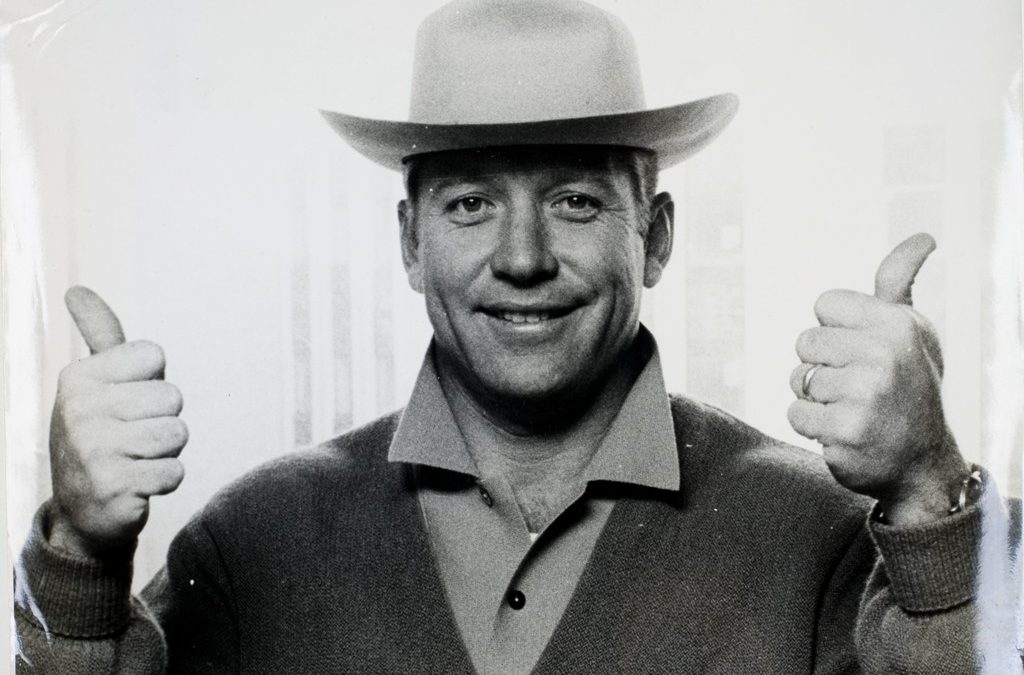

Mickey Mantle sits behind a wooden table surrounded by sentinels who keep the crowds moving and the communions brief. Hundreds file by, quietly, respectfully, as if in a religious procession. They are relieved to find their hero has retained his dignity, his diffidence, and his hairline. Under a maroon sweater, his shoulders are still massive, his demeanor still regal. He will rarely look up to see the faces of the pilgrims who have journeyed so far and waited so long for his cursive blessing. Few will dare a conversation. They must be content to present their offering and watch the man who stroked 536 home runs now drag a felt-tipped pen across their memories.

He will write “Mickey Mantle” quite legibly, somewhat delicately, on baseballs and bubble-gum cards and paperback books and Little League uniforms and old Life magazines and ticket stubs and mugs and Polaroids with his mug and body casts and naked skin and anything that will hold ink. He will write Mickey Mantle 200 times this afternoon, and then he will do it again tomorrow.

“It’s exhausting, but I don’t really mind,” says the autographer. “It’s just this tension in the air. I want everyone to be happy. Especially when it’s in my place, in the hotel that pays me. I have to be careful about the time. If you stop and personalize every autograph and talk to everyone, there’s gonna be a lot pf people real mad. So my main goal is just to get everyone through the line at least once. When these people leave here, if they don’t get what they came for, they’re gonna blame me. Not Whitey or Billy, but Mickey Mantle.”

“It’s like it’s happening to someone else. Like this Mickey Mantle is some other guy.”

Neither sullen nor charming, Mantle signs beyond his two-hour allotment. He is so dedicated, so diligent that one wonders if signing his name isn’t a form of penitence.

“I saw Mantle push kids aside,” writes a former teammate. “He closed bus windows on a bunch of kids who wanted his autograph. He refused to sign baseball in the clubhouse before games. Everybody had to sign except Mantle. There are thousands of baseballs around the country that have been signed not by Mickey Mantle but by Pete Previte, the clubhouse attendant.”

There will be no autograph pinch-hitters today. Mantle earns a living by signing his name for $5,000 per appearance. Each time he comes to the Claridge Hotel, boxes of baseballs await him. And when he walks into a restaurant, men, women, and children too young to have seen number 7 roam centerfield for the Yankees will ask him to sign his name.

“It’s been amazing how good my name has been,” says Mickey Mantle with more wonderment than hubris. “I guess people think of Jack Armstrong when they think of me. This is the biggest year of my life. I’m more popular now than ever. I’ve been real lucky. Lucky to have played with the Yankees. Lucky my appearance hasn’t changed over the years. Lucky my name is Mickey Mantle. It’s easy to remember. You know, I haven’t played ball in over 15 years. Long time.”

Later, under less stress, Mantle tells of strangers who hug him on street corners and weep; of people who send him scrapbooks—he has over 50—that document every event of his life; of a woman who paid him $3,500 to attend her husband’s birthday party; of throngs that grow unruly at the sight of him. Mantle is befuddled and bemused. He calls it “very strange” to have affected so many people he’s never met, to be so admired for acts he can no longer perform. Signing autographs is one thing, but the clipping and the awe and the tears….

“It’s like it’s happening to someone else,” he says. “Like this Mickey Mantle is some other guy.”

Sometimes, it must feel as if it’s the other guy who has all the luck. Tom Catal doesn’t operate on luck. “Mickey Mantle guarantees success,” says the stockbroker-turned-memorabilia organizer. “I’ve been doing these shows for five years, and every year, he gets more popular. In Detroit, he almost caused a riot. Same thing in Kansas City. Mickey Mantle can outdraw God. By 50 percent. I’ve tried to figure out the appeal, and all I can come up with is he’s white, he’s a living legend, and I will never do another show without Mickey Mantle.”

Four dollars gets one autograph by Hall of Famers Duke Snider or Harmon Killebrew. Six dollars buys a Willie Mays or Pete Rose. Mickey Mantle goes for seven simoleons. Who would have guessed that the number of his back would end up his price?

Mantle and television flourished simultaneously. He was in America’s living rooms more than Uncle Miltie.

Mantle is not only the most popular baseball player alive, he is the most popular athlete, period. Basketball players are too tall and their teams play only 80 games and in relative obscurity; their playoffs aren’t even televised. Football players are too big and play less than 20 games; who can see their faces beneath all that gear? Baseball players do what every kids does naturally, only better. And longer. Baseball is seven months a year and covered daily by the press. We read about players’ salaries, their families, their aches and pain, their exercise regimens; we learn the names of their lawyers and doctors and favorite chefs; we know their goals and fears, when they’re happy and when they’re not. We know, in fact, more about some baseball players than we know about our friends.

We surely see them more—100 games a year are televised, not to mention games-of-the-week, All Star contests, and the World Series.

Mantle and television flourished simultaneously. The Mickey Mantle Show ran for 18 seasons in New York. He was in America’s living rooms more than Uncle Miltie. And his scenario had the stuff of dreams that would make writers blush. Our leading man, a poor, handsome hunk from a little southwestern mining town called Commerce, comes to the Big City, conquers the Big City only to be confronted by the smirking ghost of Babe Ruth, and a press corps that eats hayseed heroes for breakfast, and five boroughs of Bronx cheers for not being perfect.

Each time Mantle took the field, there was the promise of glory or tragedy or both. At 21, when he hit a baseball as far as a baseball can be hit—565 feet—a public relations man actually measured the distance, coining the phrase “a tape measure home run”—setting up an impossible standard. Every home run Mantle hit thereafter was to be measured, and few would measure up. With a body that refused to cooperate with destiny, Mantle personified the conflicts of drama: strength vs. frailty; will vs. fate. He was an undeniable attraction.

The green curtain of money that now separates the hero from his worshippers had not yet been lowered. In his sixth season with the Yankees, Mantle hit .353 with 52 home runs and 130 RBI. He won the Triple Crown and MVP. He earned $32,000 that season, and was offered a $5,000 raise for the next. Statistics like that would make a player a multi-millionaire today.

Mickey Mantle is the last working class sports hero; fame, not fortune, has been his reward. He is the most famous athlete in America. He started getting famous at age 7—the number he would wear—when his father invited the men of Commerce, Oklahoma to watch little Mick play ball in the backyard.

Mutt Mantle, who had tried to escape the lead mines by hitting baseballs, made it only to the semi-pro level. Determined to have his son earn a living above ground, in the open air, he named him after Mickey Cochran and into his cradle put not a teddy bear but a baseball mitt. When Mickey entered kindergarten, when all the other boys were dressed in their Sunday best, Mickey was wearing a pair of his daddy’s tailored-down baseball pants.

After school each day, three generations of Mantles would prepare for their future. Granddad would pitch left-handed so the kid could swing righty, and Mutt would pitch right-handed so the kid could swing lefty. Not only did Mutt Mantle know a major leaguer when he saw one—or sired one—he also predicted the advent of platooning and knew his son would play every day, and make good money, if he were a switch-hitter. Mickey Mantle would be the first switch-hitter with power, hitting home runs both lefty and righty in 10 different games.

Mutt Mantle left nothing to luck.

“He bragged on me all the time,” says Mickey of the man he mentioned 35 times in the first 20 pages of his autobiography. “His friends would come over on weekends, and he’d say, ‘Come on out here and watch little Mickey hit the ball or shag some flies.’ He’d brag on me all the time, and his friends did too. I can still hear them sayin’, ‘Oh boy, he’s gonna be a big leader someday, Mutt.’ That’s all I ever heard, all I ever lived for, to be a ballplayer. I knew it would make my dad real proud. I loved showing off for him, just love it. Luckily, I could run and hit and throw some.”

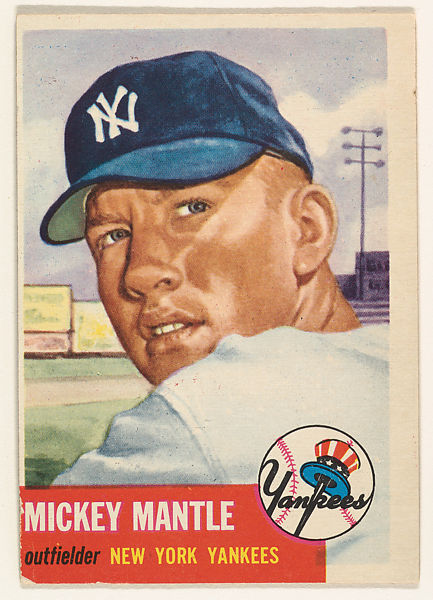

He could do those things so well that he was legend before he played a single inning as a Yankee. In spring training in 1951, sports writers heard wild rumors about this Okie phenom and skeptically traveled Phoenix to take a look. The rumors were transformed into reports that stated, without reservation, that Mickey Mantle could run faster than Ty Cobb, bat right-handed better than Joe DiMaggio, left-handed better than Ted Williams, and bang the ball farther than Babe Ruth with either hand: four greats rolled into one kid with wheat-colored hair from a hamlet with a small population than the bleachers of Yankee Stadium.

Mickey Mantle was fun to say, impossible to forget.

“From the start of spring,” wrote Stan Isaacs in the New York Compass, “the typewriter keys have been pounding out one name to the people back home. No matter what paper you read, on what day, you’ll get Mickey Mantle, more Mickey Mantle, and still more Mickey Mantle. Never in the history of baseball has the game known the wonder to equal this rookie.”

The torrent of stories reached such proportion that, as Dick Shaap wrote, “There wasn’t a single baseball fan who could read, listen or look at pictures who hadn’t heard of Mickey Mantle. In the space of six weeks, he had achieved the same degree of renown that it took Babe Ruth years to acquire. He still hadn’t swung a bat in a game that meant anything, but Mickey Mantle was a national figure.”

Some players bring nicknames from their childhood; others have them determined by some quirk in physiognomy or temperament or mannerism. Only the best earn sobriquets based on merit. It took Mantle a few mean cuts and a couple of drag bunts before the writers rechristened him “Sweet Switcher” and “Master Mickey” and the “Commerce Comet.” The inventions were snappy enough and, more important in a world that adores alliteration, alliterative; they were attempts to instantly elevate the 19-year-old to the ranks of “Joltin’ Joe” and the “Splendid Splinter” and the “Sultan of Swat.” It was ironic, and just plain stupid, for anyone to try improving upon the ultimate sport appellation—nothing could supplant that which Mutt Mantle had already designed. (Didn’t that man overlook anything?

Mickey Mantle was fun to say, impossible to forget, and condensed volumes into two words. Those soft, sensuous M’s were most likely the first sounds anyone uttered when wanting Mom; sounds that brought warmth and satisfaction. If baseball is a child’s game played by grown-ups, Mickey (as in Mickey Mouse) conjures youth, as Mantle does adulthood. With Joe DiMaggio on the verge of retirement, it was obvious that this kid was being handed the mantle of Yankeedom. For those unable to grasp the symbolism verbally, it was reiterated numerically: Ruth wore 3, Gehrig 4, DiMaggio 5, Mantle was given 6. The dynasty would survive. Mantle was to be the next King of New York City. Long live the Damn Yankees.

And how did the heir apparent react to the premature ordination? Mantle’s manager, Casey Stengel, shielded his new star from the press and answered for him: ‘The boy’s never seen concrete before—how do ya think he’s reactin’?”

By mid-summer, Mantle was sent to the minors, having produced nothing prodigious save his number of strikeouts. It was the start of a passionate love-hate relationship with a public that felt betrayed by the little prince before he had a chance to perform.

Without fanfare, with other rookies, Mantle rejoined the Yankees near the end of the ’51 season. His number was 7, providing some breathing space between him and his royal predecessors. He did nicely and helped the Yankees into another World Series, a Subway Series. It was against the New York Giants, and it would alter Mantle’s, and maybe baseball’s, history.

In the second game, top of the fifth inning, with Mantle in right and an aging DiMaggio in center, a line drive was hit between them. Mantle called for the ball, sprinted into the gap, and caught the spikes of his right shoe on a drainage cap sticking up from the ground. Mantle went down, and out. He had torn the cartilage and ligaments of his knee.

That he already suffered from osteomyelitis (an incurable and progressive bone disease) did nothing to aid the healing process. In fact, the knee never did heal. But the infirmity would become as much a part of the Mickey Mantle mythology as any of his superhuman feats; it would handcap his career, nurse his popularity, and forever force fans to wonder how good he could have been had his luck been an inch better.

Few fans remember, however, that the ball he was chasing was hit by another promising rookie whose career would be compared to Mantle’s for the two decades in which they played, and beyond. It was, in some unworldly way, Willie Mays knew of the upcoming rivalry and tried to get an edge.

Mays and Mantle. The best of their generation, they were a study n complement and contrasts. Both were centerfielders in New York; both were blessed with every physical gift; but Mays was black, a National Leaguer, a man of grace and instinct, while Mantle was white, an American Leaguer, a man of brute strength, determination and bad habits. Which one you preferred said more about you than them.

“They brought me to Atlantic City to combat Willie Mays,” is how Mantle succinctly sums up his job for the Claridge. Five years ago, Willie Mays was hired by Bally Park Place to promote the new casino, calm the city’s have-nots. Associating with a winner who had dazzled New Yorkers was savvy strategy; the Big Apple is the bull’s eye of the casino target audience. For his association with Bally, Mays was promptly banned from any baseball activities by its commissioner. It was an absurd, unjust gesture: you cannot erase memories or evacuate the Hall of Fame.

Mantle rents his name and his face and his fame for whatever the traffic will bear. It’s how legends make ends meet.

Last year, when the Claridge hired Mantle, he too was ejected from the sport. You may not be able to rewrite history, but you sure can repeat it. Here they are, the yin and yang of baseball, equally exiled, sweetly bitter, and earning as much lucre from their personas as they eve did from their talents. News of their employment inspired crosscurrents of pathos and anger; pity for the heroes reduced to shilling for casinos was cut sharply with the awareness that they each pocket $100,000 annually.

How cruelly we demean our icons; how susceptible they are to demeaning. Mays and Mantle being cut off from their sport is tantamount to falsifying a generation’s childhood, severing its connection to grandeur. While Mays was openly wounded, Mantle chose not to acknowledge any pain.

“What the hell did I do to get banned?” he asked at the time. “I haven’t done anything for 14 years. I went to spring training for two weeks with the Yankees as batting instructor, which I am not. I couldn’t teach somebody how to hit for the life of me. Autograph-signer is more like it. Billy Martin used to say, ‘If we need to teach someone how to strike out, I’ll get you Mick.’ All it was was a paid vacation for me and Merlyn (his high school sweetheart whom he married at 20). I took this job at the hotel cause I needed the money.”

Real money always eluded Mantle. His career was over before free agency and the seven-digit salaries began. His salad days were not garnished with tasty investments. During his first full season, a city slicker sold Mantle 3,500 shares in the Will Rogers Underwriters Association. Turns out there was no such organization. In 1956, Mantle incorporated and endorsed Wheaties (for $2,000), Charles Antell hair tonic ($2,000), cigarettes and cigars ($3,500), cheese, T-shirts, soap, bubble gun, baseball gloves, greeting cards, and a pancake mix called Batter-Up. He appeared on the Perry Como Show and compared the breadth of his back with Kim Novack’s. And he cut a record with Teresa Brewer.

Mickey Mantle meant magic. In a system where Madison Avenue directs the hero traffic, Mantle was finally, indelibly, deemed an American Hero. He naturally assumed that that status would support him when he finished playing, saying he wanted to be rich and play golf every day when he retired. Our hero opened the Mickey Mantle Country Cookin’ Kitchen after his playing days. He came up with his own advertisement: “To get a better piece of chicken, you’d have to be a rooster.” It was never used. And the chain’s weakest link turned out to be its first. Mantle got plucked. Almost literally. Turns out his two business partners had taken out insurance policies worth $2 million on Mantle life. Mantle’s lawyer demanded the insurance agent, Leroy Kerwin, terminate the policies. Soon thereafter, Kerwin himself was terminated, his body found in Toronto, buried in the ground head first, his toes exposed during the spring thaw.

Kerwin had been involved in similar scams in five different states.In Oklahoma, a rancher was murdered one week before his enormous life insurance policy lapsed. The rancher’s widow was due $16 million. The insurance agent was Kerwin. The case in still in the courts.

Mantle realized he was safer stealing second base in front of 50,000 people than residing quietly in Dallas. He stayed out of the public eye for a long spell, fearing his life was in constant danger. Eventually, cautiously, staying local and low-key, he ventured out. Having demoted himself to the minor leagues of celebrity, he worked for wholesalers and retailers and he signed autographs at grand openings and judged Mickey Mantle look-alike contests in shopping centers.

In time, he signed on with a beer company and a chemical company and even an insurance company. He appeared in a feature film and dined with President Ford at the White House. He now earns a six-figure salary for an outfit called TimesSavers that somehow gets credit cards for people who have no credit. He recently signed on with a publisher to have another autobiography ghost-written. And there’s the gig at the Claridge.

Mantle has no agent. He says the agents always made out better than he did. He takes the offers as they come. And they’re coming hot and heavy nowadays. Mantle rents his name and his face and his fame for whatever the traffic will bear. It’s how legends make ends meet. If they’re shy, they get over it; if they don’t like travel, they swallow some pills and apologize to their family; if they don’t know why the hell anyone wants them, they check their identity crisis at the door and pick it up with the check on their way out.

Gary Serafine, public relations director at the Claridge, sings Mantle’s praises: “We can be relatively sure that high rollers will drop between $50,000 and $100,000 per year. We want them here rather than going to Las Vegas. What do we have that Vegas and Lake Tahoe don’t have? Mickey Mantle. I’ve dealt with lots of superstars in this business, and there is only one that inspires true awe. The Mick.”

Last month, a plane-load of small whales from Dallas was shuttled in for the Mickey Mantle Excursion. Everything was gratis: the golf they played with Mantle, the dinners they ate with Mantle, the cocktails they enjoyed with Mantle, the show they saw with Mantle. If just 20 players a year drop $50,000 each, one million dollars accrues in the Claridge coffers. Or: if five players lose only $20,000 apiece, Mantle’s annual salary is covered.

Though not everyone likes dealing with The Mick, not his mystique, his profanity or his hillbilly pace. An executive at the ad agency that handles the hotel says, “He’s the most arrogant celebrity I’ve ever known. A chauvinist who likes his liquor more than people. Everyone is intimidated by the great Mickey Mantle, and he is aware of that fact. We never know where he is or when he’ll show up. Either he can’t be bothered or can’t be trusted in public. We helicoptered him up to New York recently for one of those morning talk shows and he just sat there stiff and silent and sullen. He’s a real boob on the tube. He has nothing left to say. You’ll see. Have you spoken to him yet?”

Not yet.

Getting an interview with Mantle has taken almost a year. I have been stood up a half dozen times, always at the last minute. I try to erase all that from my mind as I knock on Mantle’s hotel door. A waitress, having delivered burgers and beers for lunch, is just leaving. She says Mantle is a fair tipper, 15 percent, compared to many other celebs. She knows who Mantle is, she says, because the day he retired was the only time she ever saw her father weep.

I am greeted by Mantle’s traveling secretary, an attractive woman with short red hair and tall black boots. She offers me free reign of the well-stocked bar and says Mick will be ready soon.

“How long will the interview last?” she wants to know. “Ten minutes?” “I was thinking more like an hour,” I say, pouring myself a vodka. “An hour! Mickey doesn’t have that kind time.” “We’ll just play it by ear,” I say squeezing a lime.

Billy Martin strolls into the suite, mixes himself a drink, and plops down on the sofa. Martin has been “like a brother” to Mantle since they played together in the early ‘50’s, when they starred as the Martin and Lewis of the Yuck-Yuck Yankees, and then co-starred as the Tag Team Drinkers who tore up the Copacabana one night.

I happen to be holding a New York Times where a letter to the editor suggests that Billy Martin be the new commissioner of baseball so that all the owners, not just George Steinbrenner, can have the pleasure of firing him. (The Yankee owner has had that pleasure three times, so far.) I read the letter to Billy Martin. It is a mistake. He glowers at me. He has been known to take swings at strangers for lesser offenses. I decide it is a good time to get that twist of lime. Mantle, who has entered the room and has heard the exchange, invites me outside.

“Billy’s at the lowest point in his life,” he whispers on our way to the third room of the suite. “He’s been fired by Steinbrenner again in an awful way, and Steinbrenner doesn’t give a shit about anybody’s feelings. He milked Billy for all he could get and then screwed him. Billy’s handling family problem, too. He is in a real bad state. And still, just because I asked him, he came this weekend for the baseball show. That’s a real friend.”

His three best friends are Billy Martin, Whitey Ford and Roger Maris. They are among the few men in America not blinded by Mantle’s name or fame.

Billy Martin’s loyalty should come as no surprise to Mantle. It has been demonstrated before, if we are to believe the oft-told Tale of the Hunting Trip. During one off-season some years back, the two of them drove up to a farm where Mantle had gone hunting most of his life. Following protocol, Mantle asked permission of the owner to use his great stretch of forest and streams. Martin waited in the car. Mantle was given the green light on one condition: The farmer told him that his favorite mule was old and suffering and should be put out of his misery, but no one in the family had the heart to do the deed. Mantle was asked, as a favor, to assassinate the family mule. He agreed.

He walked out to the car, shaking his head, and said to Martin, “Can you believe this cocksucker? Known him my whole life and he says I can’t go hunting on his property cause the Yankees didn’t make the World Series. I’m so mad, Billy, I think I’ll … I’ll kill his goddamn donkey.” With that, Mantle marched to the barn and took aim. Martin tried desperately to dissuade his friend. Mantle pull the trigger. Martin was in shock. Momentarily. He recuperated and said, “Mick, if that cocksucker got you so made, I’ll show you what kind of friend I am.” And Billy Martin shot three cows in the head before Mantle could explain the joke.

Coming to Atlantic City during a deep depression must be child’s play for the ex-ex-ex Yankee Manager.

Mantle opens a beer and turns on the television to a football game. He says his three best friends are Martin, Whitey Ford and Roger Maris. They are among the few men in America not blinded by Mantle’s name or fame. Mantle was so respected by the men who knew him best, six teammates named their sons after him. Mantle also named his first son after himself.

“Worst think I ever did,” he says now. “I wish I hadn’t’ve done it ‘cause nobody bothers my other kids, not David or Billy or Danny. They can do anything, got to school or work without any problem, but as soon as someone finds out Little Mickey’s name is Mickey Mantle….”

Mantle stops suddenly, takes a swig of beer, and states at the television. He shifts his weight. He does not want to get emotional, does not want to talk about the curse of having the name. He can’t help himself.

“Little Mickey never did play Little League or high school ball or anything. He just couldn’t. Imagine trying out for a team and saying your name is Mickey Mantle. He couldn’t do it. But five or six years ago, when Little Mickey was about 25, he started playing softball around Dallas. That slow pitch stuff. And he’s a real good athlete, 6-1, 190 pounds, and can run like hell. He could hit and throw and everything. Played great centerfield. At least that’s what everyone told me, ’cause I never did see him play. So he came to me one day and said, ‘Dad, I’d like to try to play baseball.’ Goddamn, I says, have you ever played real baseball once in your whole life? ‘No,’ he says to me, ‘but I’d sure like to try.’ ”

“So I took him to spring training when Billy was the manager, and we called him Rocky so people wouldn’t bug him to death about Mickey Mantle. And he didn’t do bad. They sent him to Alexandria in the minors, and the manager there is an old friend of mine. After two months, he calls me and says, ‘We’d love to have, Mickey, cause people come out to see him, but to tell you the truth, as old as he is and with such little experience, I think it’s a waste of time.”

“Every time Little Mickey would strike out, the fans would yell, ‘You’re just like your old man!’ And he’d get real embarrassed. Your baseball fans can be cruel. So I told him to come home and get a job. But if Little Mickey would’ve had my dad, he’d be a major league ball player today. I just know it. He’d be a star. He has all the tools. It’s just that I never did work with him, never had the time. I was never home during the baseball seasons.”

Another beer in unscrewed. The college football game is watched in silence until a kid gets carried off the field. Mantle wonders if the kid is seriously hurt. He recalls his high school football days, when he was a running back until his father wisely decided it was too dangerous. Mantle watches every football game he can. He watches no baseball. None. Not on television, not at the ball park. He doesn’t read about it, and he doesn’t care about it. Mickey Mantle banned baseball long before it banned him.

He says it’s just too boring. You get the feeling it’s too painful for him to watch youngsters rounding the bases, basking in the limelight, not yet knowing there’s no place to go after they cross home plate.

“When I think back, my only regret is that I didn’t play longer. If I could’ve played until I was 41, like Rose and Musial and Williams, I could’ve been at the top of all those lists. If I was someone else, I would’ve stayed around, but I was Mickey Mantle and I was letting my team down. They wanted me to play longer, but I really should’ve left three years sooner. I couldn’t. Baseball was all I’d ever known or lived for. There I was, 36, not even in the prime of my life, and I was through. Done. That’s what keeps hurting.”

It’s a long hurt. And those stats keep changing, pushing Mickey Mantle’s name deeper into the pack. He never reached certain milestones by which greatness is judged. He didn’t collect 3,000 hits or 2,000 RBI or a .300 lifetime batting average (it was .298). He is sixth on the all-time homerun list and third in strikeouts. He was most valuable player three times and is one of only four men since World War II to win the Triple Crown. He was in 12 World Series and hit 18 home runs.

“I think your life runs in cycle. You’re lucky for a while and then it goes the other way.”

Still, Mantle continually talks about “those guys in the record books” as if he doesn’t belong. “I was a real screw-up. I could’ve done exercises after the knee operation. But I didn’t. I never took care of my body. I was out till 3 in the morning the night before a doubleheader. The records didn’t mean anything to me then. I didn’t think about those things. I was young and stupid. I thought baseball would never end. Not for me.”

Mantle thought that retirement would be like a nice, fat change-up down the middle of the plate instead of the nasty curve it has turned out to be. Of course, he hadn’t planned on retirement at all. He hadn’t had to plan any further than his next at-bat since he was a teenager. Retirement was for other folks, those who thought they would live a long life with lots of sunny grandchildren and shady palm trees. Mantle expected to be dead before he was 40. Family tradition. “My father died of Hodgkin’s disease when he was 39. He dad and two brothers all died before they were 40 from the same thing. It’s hereditary, you know, so I had this feeling my whole life that I wouldn’t make it past 40 had I lived like that. I burned the candle at both ends. If I had to do I tall over, I’d’ve done it different, real different.”

Mantle reached 40 and then 45 and at 50 he started to absorb the notion of a future, started to learn that he twilight years were not when you could no longer beat out a bunt or catch up with fly ball, and wouldn’t you know, just as Mantle was staring to enjoy his longevity, his youngest son, Danny, 24, would fall prey to the family inheritance and contract Hodgkin’s. It skipped a generation. Now Mantle has this to deal with.

He tries. He really does.

“I think your life runs in cycles,” he says. “I think you’re lucky for a while and then it goes the other way. If there’s somebody up there, I think He tests you everyone once in a while. He put you on top of the mountain and then, all of a sudden like, one of my kids gets real sick. There’s always the other side of the mountain. I don’t care if you’ve got all the money in the world, nothing takes the place of your health or your son or you mother or dad. You’re lucky for a while, and then, you’re unlucky for a while. I’ve been up and I’ve been down, real up and real down.”

After a long pause, after he opens his third beer, he says, “That’s all for today.”

The sky, the sea and the sand form a moist monochrome the next day. Losers march aimlessly on the endless Boardwalk at 7 AM on Sunday mornings. The sun too has no luck.

Inside the lobby of the Claridge, a lady from public relations holds a black baseball bat in her small hands. She is here to make sure Mickey Mantle is on time for a photo session. It will be a four-color layout. If she wakens him from a deep sleep, she may be interrupting one of his recurring nightmares, maybe the one where he’s locked out of Yankee Stadium because no one recognizes him or maybe the one where he’s a pole vaulter who, after elevating over the bar, begins a fall that never ends.

The photographer and the subject arrive together. The former complains about the lack of sunlight; the latter about his lack of sleep. The trio goes into the pale morning. After complimenting Mantle on his attire and his grooming, the lady from the hotel delicately suggests he pose with the baseball bat she has brought along. The subject declines brusquely, resolutely. He knows that a 52-year-old man in a dark blue suit standing before an old grey hotel in Atlantic City with a black baseball bat would look absurd. The snap of his retort rouses him from his stupor. He tries to soften the parry by explaining he never used a black bat in his life. The lady from the hotel says she could run upstairs and find a white one.

Without props, Mantle stands before the hotel that pays him to do such things. The photographer selects one of a pair of cameras handing around his neck and gets to work. A young woman passes by. The former baseball star calls out to her, asking if she would like to have her picture taken with him. He is ignored.

Moments later, another woman happens by, and she, too, is invited to join the photo session with the added incentive of some “action shots” with the Mick. This woman does not break stride. The photographer does not miss a click. The lady from the hotel just has to say something now: “Oh, Mickey,” she says. “You’re so bad!”

Still searching for the right light, the photographer asks Mantle to walk around the large lawn. Maybe it’s worse in the mornings, maybe I’ve never seen Mantle take so many steps in succession, but he limps so dramatically that a cane would not be out of place. It is startling. I don’t want to mention it. I do anyway. Mantle says he has grown accustomed to the pain, but the ailment is degenerative, and he may have to get an artificial knee soon, and he fears it will end his golfing, his only activity. Hunting, tennis and even table tennis are well beyond his capacity now. He cannot stand very long, much less move around a forest or a court.

He is heading straight toward an irrigation nozzle protruding from the grass when I point it out to him. We both think of the accident in the 1951 World Series, and he stops to stare at the drain cap and curse it a blue streak until he bends over and picks up a copper penny from the green grass. He kisses it, places it in his shoe, and says, “Brings good luck, don’t it?”

And then Mickey Mantle limps to the spot where the photographer thinks he will look good on this gray day.

[Featured Image: Gordon W. Gahan (1966), via the Harvard Art Museum]