O’Connell Driscoll is a great name for a writer, the kind of byline that sticks. Trouble is bylines are easily forgotten and the history of magazine writing is littered with terrific writers who are neglected and Driscoll is a classic example. Between 1974 and 1985, he wrote seven exquisite celebrity profiles—five for Playboy, two for Rolling Stone—operating in perhaps the last moment when writers could climb inside a subject’s skin and even their skull. Driscoll’s stories were all about access. He was a purist in the mold of Lillian Ross. He didn’t offer analysis or exposition or as much as a dollop of biography. He didn’t ask questions. He just wrote what he saw and heard.

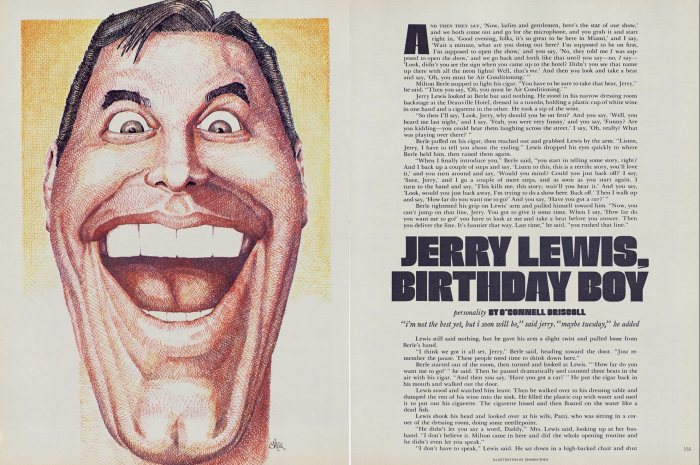

His first piece, published when Driscoll was a senior at USC, a 13,000-word Playboy profile of Jerry Lewis, stands as the Citizen Kane of celebrity profiles. There’s no magazine debut like it that I know of—an even more pared-down version of the fly-on-the-wall style practiced by Ross and Gay Talese.

“My stories are practically all people talking,” says Driscoll. “That’s much more interesting to me than a lot of exposition.”

“Jerry Lewis, Birthday Boy” is a masterpiece of the genre, a freakish confluence of time and place, opportunity and talent. Only in 1973 would a star as big as Jerry Lewis, despite the fact that he wasn’t a draw at the movies anymore, let a writer—a writer!—hang around for three weeks.

Lewis gave Driscoll more access than he would ever experience again, so in a sense the kid’s magazine career was all downhill after the first story. He got an agent and wrote six more stellar profiles, signed a contract to a write a novel that he never finished, and messed around Hollywood polishing up scripts and working on screenplays that went unproduced. Finally, in 1992, he moved to Santa Barbara, got a square job, running the men’s clothing department at Nordstrom and left the writing life behind. Just like that, O’Connell Driscoll was gone—poof!—a stand-out talent now another byline on the pile.

“He was like a character out of a Whit Stillman film,” says Stephen Randall, a senior editor at Playboy who worked with Driscoll on several stories. “He lived in an elegant duplex. The furniture was fussy, not the furniture a young person would have. As was so often the case with many of my successful interviewers, I could never understand why anyone would want to talk to them. I know I wouldn’t, and I liked their writing. But the great ones have an ability to get people to open up and say more than they intended to say.”

Driscoll was born in 1951 and raised in Los Angeles. His mother, from a big Irish family, had been a fashion model in New York, and his father, who attended Notre Dame at 13 and was something of a boy genius, became a fine draftsman, worked as an animator at MGM (including Anchors Aweigh! with Gene Kelly and Jerry of the Tom and Jerry cartoons) and later made 16mm industrials. His parents appreciated culture—art, books, and movies mattered.

Young O’Connell showed no gift for drawing but had a conspicuous talent for writing. “I could always write an essay and get myself out of trouble,” he says. His dad gave him a copy of Strunk & White’s Elements of Style, introduced him to John O’Hara, Ross Macdonald and, O’Connell’s favorite, Raymond Chandler. The old man was suspicious of anyone who was prolific. “When I was a young boy he said to me, ‘Writing is very difficult work. And only comes easily to people who have no talent for it.’ ”

Driscoll spent his sophomore and half of his junior year of high school at Georgetown Prep and hated being away from home. During Christmas break of his sophomore year, his dad gave him a copy of Tom Wolfe’s first anthology, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. “This guy writes like Gidget talks,” his dad said. “Pow, Bang, Wow.”

Driscoll read it cover-to-cover on the flight back to school and was hooked. He didn’t want to be a musician or a painter or a movie director. He wanted to be a magazine writer in the New Journalist style.

“I didn’t take creative writing classes, but I had an English teacher who introduced me to the New Yorker style— clean, clear prose, the declarative sentence. I also learned about what he called the courtroom analogy. In a courtroom you can testify to what you have seen, and what you have heard but you can’t give opinions about it. I found that to be very useful. I tried to write things that way so that if anyone else was in my position they would have seen what I had seen and heard.”

A few years later, Driscoll was at USC. He’d started as an English major but moved to psychology, which was probably more useful training for a magazine writer, anyway. The newness of New Journalism was on parade at Esquire and Rolling Stone, New York and Harper’s. Driscoll gobbled it up like most kids bought rock albums: Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Hunter Thompson’s Hell’s Angels—“Hunter was a one of a kind and not to be imitated”—and Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. “Radical Chic,” Tom Wolfe’s unsparing 1970 exposé of the Leonard Bernstein’s, was a major influence, not so much Wolfe’s prose but his ability to set a scene and take you inside a world.

Through one of his father’s connections, O’Connell finagled his way on the set of John Cassavetes’s scruffy romantic comedy, Minnie and Moskowitz, where he spent enough time to write up an on-location magazine piece. He sent the story to Esquire and got shot down, with a curt note to prove it. Then he sent it to Arthur Kretchmer at Playboy, who liked it but turned it down because Cassavetes had recently been interviewed in the magazine. The timing was off. Keep pitching, Kretchmer said. So that’s just what O’Connell did. For more than a year, until he drove Kretchmer nuts.

Finally, one Saturday morning during his senior year, Driscoll was in a Beverly Hills coffee shop scanning the L.A. Times when he read that Jerry Lewis was making The Day the Clown Cried, a misbegotten movie about a clown sent to a concentration camp during WWII.

“I knew where Jerry Lewis lived in Bel Air,” says Driscoll. “I wrote him a letter saying I really wanted to write something about him, and drove it over to his house. There was a guard outside and I handed the letter over. He said, ‘Oh, he’s up in his office now.’ I drove home to my parents’ place, not that far away, and when I got there, the phone was ringing. And it was Jerry.”

“I’d like to speak to O’Connell Driscoll please,” Lewis said.

“This is O’Connell Driscoll.”

“Nobody is named O’Connell Driscoll.”

Lewis, on the verge of turning 47, liked the kid. “I was so young,” says Driscoll, “and I was so gentile it just cracked him up. They didn’t see me as threatening. The rest was his idea. Going to Europe was his idea. He was like, ‘Do more rather than less.’ ”

So, Playboy assigned a standard 3,000 word story and Driscoll spent a few weeks with Lewis—in L.A., Miami Beach, Germany, Geneva, New York and then back to Hollywood where Lewis was editing The Day the Clown Cried.

“I was living my dream,” he says. “I was working for Playboy. I was on the airplane with Jerry. Everything just fell into place for me. Nothing ever worked out like that ever again.”

Driscoll was polite, quiet, innocuous.

“I remember something that Joan Didion said,” he says. “She wasn’t a great interviewer and sometimes when she was with the subject, she couldn’t think of anything to say. She would just be sitting there quiet and then they would blurt something out because it was uncomfortable. She credited her shyness or inability to be an aggressive interviewer as an asset and I was like that too.”

Lewis had no idea what he was in for when he let the innocent O’Connell hang around because O’Connell heard and saw everything.

“In real life he was very funny, I mean, no surprise. But in everyday life, not just on stage. When he said he was going to Germany he said, ‘Yeah, I have an aunt who’s a hanging lamp in Munich.’ Later, we were in a car in Germany and a bunch of school kids went by and Lewis looked at me and said, ‘Jesus, even the fucking kids speak German over here.’ ”

As he learned from his father, writing is going to be difficult if you want to make it good and Driscoll spent a couple of months writing the piece. He was more influenced by the dialogue-driven style of George V. Higgins and John O’Hara than the New Journalism flash of Jimmy Breslin or Hunter Thompson.

“When I was writing I would always hear my father’s voice in my head saying, ‘Do we really need this?’ ‘Get on with it.” And: ‘Keep it lean.’

“I was aware enough to know that I had a lot of good stuff,” he says. “At the same time, I was nervous all the way through. I was always nervous when I was writing. I knew who I was competing against and I didn’t want to embarrass myself. I wanted to come off like I belonged. There was only one draft—what I handed in, 13,000 words. My father read a draft and gave me a few small notes, ‘In this graph you don’t need this sentence,’ that kind of thing.

“Playboy was surprised. They’d only ok’d 3,000 and a small amount of expenses and I had a huge amount of expenses. But they liked it. My parents were really proud that they accepted 13,000 words.

“Arthur Kretchmer said to me, ‘Do you have notes?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I’ve got notes.’ He said, ‘Well, good. Keep those notes because we’re going to get sued by everybody.’ We didn’t get sued by anybody it turns out.”

The story, featured in Playboy’s star-studded 20th anniversary issue, put O’Connell on the map and he hadn’t even graduated yet—the kid had an agent before a degree. It was a startling piece, nothing but direct scenes of Lewis unguarded, arrogant, and at times—like when he pours lighter fluid in a hotel toilet and yells, “That’s it, burn! Burn, you motherfucker! Burn down the fucking hotel! Burn down the whole fucking town!”—downright bizarre. It also showed Lewis’s tender side, a kidding, loving side generously on display with his parents, his wife, and his son. But it’s Lewis’s volatility that made jaws drop.

“I was aware of what I was doing,” says Driscoll. “I was aware of the language he used. But there was no way around it. My allegiance was to the story not whether I was going to piss him off or not. I wasn’t there to get a buddy, I was there to get the story and make it entertaining. You can’t be too self-conscious about it. You gotta let it be what it is. And if they hate you, so be it.

“It’s not about you. It’s not about the writer. It’s about the subjects. I’m not there to make them look bad. I’m there to tell a story about the way that they relate to the world. You want to show them the way they are, but there was never any percentage in my mind to be vicious.

“I never heard from him personally. I understand why he didn’t contact me. I’m sure he was upset by some of it. But he got a lot of publicity out of it, Playboy devoting so much space to him in such a big issue and there’s no such thing as bad publicity. Years later, I felt—I don’t know if guilty is not the right word—but I certainly felt the responsibility that these were real people and I was writing and showing them as such. But it was most controversial with Jerry Lewis because of the language.”

It was the start of Driscoll’s career. He would never have it so good again.

Driscoll wrote six more magazine pieces—Raquel Welch, Nick Nolte, Peter O’Toole and Brooke Shields for Playboy, Stevie Wonder and Diana Ross for Rolling Stone. None are nearly as long as the Lewis piece but all of them are terrific. The Brooke Shields profile may even be better than the Lewis piece. And the O’Toole portrait, set in Hollywood and Ireland, is Driscoll’s personal favorite. It is irresistible. But the age of access was fast becoming obsolete. “The kind of people I wanted to write about were just not available to me,” he says. Jann Wenner wanted him to profile EST founder, Werner Erhard, and Driscoll was obsessed with getting Frank Sinatra but the barriers were already up.

“Keep in mind how the market has changed,” is how one editor at Playboy put it.

Each profile came at a cost. True to his father’s dictum, nothing came quickly or easily for Driscoll.

“No point in giving him deadlines, says Randall. “He took his time. He didn’t require much editing but he was demanding. It was impossible to get him off the phone. I never yelled at him, he just wore me down. It was always hard to get a big name to agree to give him the kind of access he wanted.”

If the quotes in his stories are suspiciously smooth by today’s standards, they weren’t out-of-step with his times. “I used a tape recorder some,” says Driscoll, “but largely it was the Lillian Ross technique. I never, ever, made up quotes or scenes out of whole cloth. Dialogue does need to be smoothed out because people speak in fragments, but that was as far as I went. I considered myself above all to be a reporter.”

“No one ever accused him of making things up,” says Randall. “Ever. And I checked. I had a chance to quiz someone close to Nick Nolte after his story was published and the message Nick sent to me was, ‘O’Connell was fucking amazing. He got everything right.’ ”

Nolte told another friend that Driscoll “is some kind of fucking journalistic genius.”

“O’Connell was high-strung,” says Randall, “I can see how self-imposed pressure and real-life pressure could derail him but, on the page, he was a purist and one of the best.”

Driscoll signed a deal to write a novel but never finished it. “I wasn’t really prepared to do it,” he says. Hollywood was no easier. “The movie business is tough. It drove me crazy.”

Driscoll, who married shortly after graduating college and had two children, got divorced and left L.A. for Santa Barbara in 1992.

“I just wanted to do something that didn’t involve writing,” he says. “I don’t want to say less taxing because working in management at Nordstrom was not less taxing. I just wanted to go to a job and was glad I was able to do something else.” Always a clothes horse, with the Hugo Boss and Burberry suits to prove it, Driscoll was well suited for the career change. Yes, he wrote a few little things for the L.A. Times and recently some small things for the Santa Barbara News-Press (and yes, he now has a bitchin’ Instagram account), but all told, they might not equal the 13,000 he wrote about Jerry Lewis.

“Looking back on it now I don’t have any complaints about it,” he says. “I did my bit. The fact that you are reading it all these years later and like it makes me feel good. Sometimes, things don’t hold up in the way you’d like them to.”

His pieces hold up, even if they are time-stamped in the same way Hal Ashby movies are dated. They are leisurely—a modern editor would rip the guts out of each one of them—but there is nothing out of place within them.

Driscoll was a seven-hit wonder, a guy who wrote full-access pieces in the small window of time when someone could actually do such a thing. The Jerry Lewis profile is every bit as good as Ross’s “How Do You Like it Now, Gentlemen?”, Capote’s “Duke in His Domain”, Talese’s “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”, or Wolfe’s “The Last American Hero is Junior Johnson. Yes!”

Dive in and see for yourself. You won’t be sorry.

“Diana Ross: An Encounter in Three Acts”

“The Post-Celluloid Tristesse of Raquel Welch”

“The Double Life of Peter O’Toole”

“Brooke Shields Works on Glass”

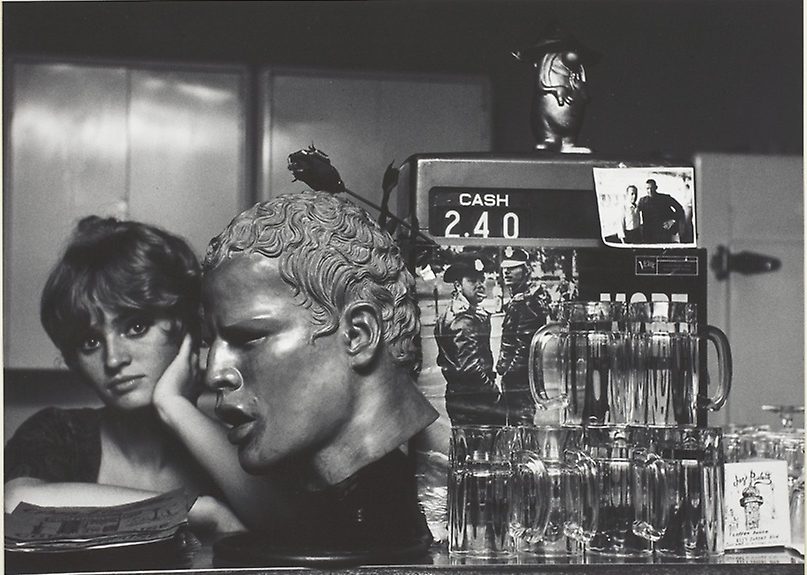

[Photo Credit: Dennis Stock via The Art Institute of Chicago]