The calm and quiet of upstate Vermont—past Burlington and Winooski, almost to the border of sleepy Canada, but before Montreal—is where Glenn Stout calls home. The world stops there. Or so it seems.

The pace of life in New England can feel daunting at times. We even have shorthand for ordering coffee in these parts — “large coffee, regular” — because time waits for no one here and no one waits for time. But Vermont is different. I’ve spent years examining the state. I wanted to go to college there and became entranced with it after the first visit that I can recall, a family trip to Stowe Mountain and to a famous sandwich shop in Burlington that’s now closed. The state has always felt like home because it puts me at ease. Normally, I can’t slow down. My brain refuses to shut off and my thoughts wander through every moment of the day. My internal monologue runs as if Michael Johnson never stopped running in those gold spikes at the 1996 Olympics.

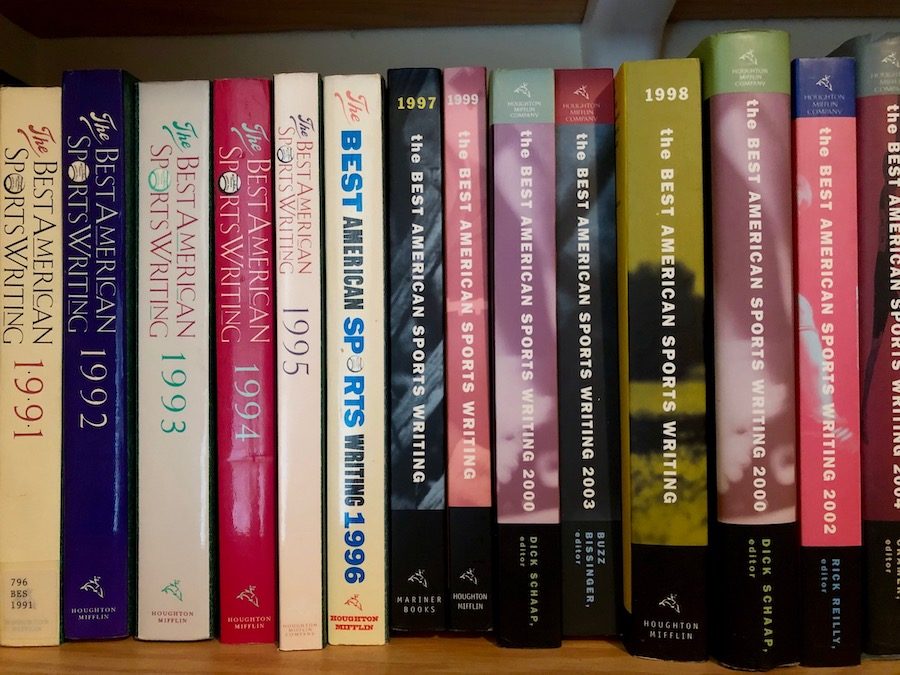

But in Vermont, specifically in Stout’s living room, it all comes to a halt after a beer is cracked open and he begins pontificating about writing, reading and what he’s seen and read since he began editing The America’s Best Sports Writing (two words, always) series in 1991. Glenn can recall his favorite stories and why they were his favorite stories in an instant. He remembers the ones that got away, the ones he put in the slush pile for the guest editor that he hoped they’d pick but would inevitably pass over for something else. His basement, where his office is, has stacks of old stories in boxes, cut out and filed.

This year will be the last edition of the book, not because Stout wanted it to end, but because the series’ publisher has decided to call it quits just before the series turned 30.

For someone who loves sports journalism, talking with Stout, a poet and librarian by trade, is like talking to John Wooden about teamwork and Phil Jackson about the triangle offense at the same time. He can both dissect a story and tell you why it works but also inspire you to believe in the magic of the story, of the properties outside of the page that make it stand apart. The first time I met Stout the plan was to write about him and his book Fenway, 1912 for The Classical, but instead it became a story about Stout the man who has shaped sports writing from afar for more than 20 years.

The series holds a spot on a shelf in may office and whenever I get stuck on a story of my own.

It was Thursday, January 26, 2012, when I emailed Stout asking if he’d talk to me. I was a lowly local news editor and reporter looking for a way to break out and work on the kinds of stories that inspired me. I told him I wanted to interview him in person. He told me it was far. I wasn’t getting paid for the story I was writing, but I knew to do the kind of work I wanted to do I needed to go to Stout. I needed to see and hear him. The details always mattered in a Best American Sports Writing story. I noticed that the first time I opened a copy of one of the yearly editions. I forget which one it was, but I was in college and I got it as a gift in my stocking for Christmas.

We agreed on a date in February and I booked a hotel room. We talked for hours after I found his “driveway” and his house. He showed me the boxes of books and the endless streams of stories. He showed me the chair he read all the submissions in by the wood stove. That night, after hours of talking, I went back to my hotel room and watched the Jeremy Lin begin his ascension to becoming a short-lived star for the New York Knicks.

Stout and I became friends after the story ran. We talked incessantly for the story and I got to know the man behind the book. I got to understand the inner workings of a book that I sought out at every used book store as I tried to collect all the issues I missed. The book became guidebook. I began to see how sports writing has changed over the years, how the ideas of “New Journalism” and “Literary Nonfiction” and now “Longform” creeped in and took over. The columns slowly disappeared and instead the stories read more and more like tome poems or movies. I could see every word and detail on the pages. I felt them more and more. The series holds a spot on a shelf in may office and whenever I get stuck on a story of my own—lost in the weeds of the endless details I try to report out to fill-in the scenes I became obsessed with—I pull a copy down and pick at random to try to understand the how and why. Usually I’m left in a heap of self-doubt, but that feeling subsides as I think about how many other writers made it into the book because Stout never cared about who wrote a story. He only ever cared about the story. The pressure subsides and I write and hope someday my own story will find its way onto one of those pages.

The Best American Sports Writing series will end after this year’s issue hits newsstands around late October. The publisher is discontinuing it at a time when journalism continues to struggle. [According to a spokesperson from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, “the decision was made in response to a changing market.”—Ed.]

Deadspin is gone. Grantland is gone. SBNation longform is gone—which Stout edited and I wrote for after we met. VICE Sports is gone. Newspapers have cut their entire staffs as venture capitalists look to wring every last penny out of them. Sports Illustrated has become a shell game. Money has dried up to do the kind of reporting needed to tell a truly great story. So many stories I read today aspire to be BASW worthy, but fall short because no longer does the industry have the time or patience to truly nurture such a thing, because, make no doubt, the kinds of stories that touch a reader and stay with them forever are the ones that take months, sometimes years, to craft.

This past fall, while reporting a story in Vermont, I stopped at Stout’s house for a few beers and to break up the monotony of reporting. We talked for hours about the problems in the industry and how those problems had affected the book — because, make no doubt, while sports may sell, sports writing is no immune to the cuts and cutbacks that may not lead to instant clicks.

The talk was both refreshing and animus. We went for a walk with his two little dogs around his property. The paths weaved and swerved. Stout told me about the book he was working on and how for years this amazing story had been glossed over, forgotten, even though it was all there. It was a gem stuck in the mud that needed to be pulled out and reexamined like so many of the stories he found before by unknown writers in unheralded publications. Stories that changed lives for readers and the writers found by a man who lived in a place far off the grid, far from hype and the awards.

He may have lived outside Boston for a while while editing the series, but he always lived off far from the cliques and hype, in a log cabin, far from it all, sifting like a miner. With The BASW, Stout changed how we write and how we read. Now that the series is gone, at least in this iteration, there is one less thing in this dying media world to aspire to. Thankfully, Stout will still be there, by the fire, reading every story that comes to his mailbox. I know that much is true because he loves the words on the page. They’re what matter the most.

Postscript: For a Best American sampler, dig into our archives where you’ll find:

“The Power and the Gory” by Paul Solotaroff, 1991; “No Pain, No Game” by Mark Kram, 1992; “The Asphalt Junkie” by Scott Raab, 1992; “Thin Mountain Air” by Pat Jordan, 1994; “Controlling Force” by Tom Boswell, 1997, and “Flesh and Blood” by Peter Richmond, 2002.