I love anthologies of magazine journalism but you don’t see them published much these days and that’s a damn shame. Safe to say everyone around these parts is grateful to the university presses for keeping the fine tradition alive. We have Mercer University Press to thank for A Man’s World, an entertaining new anthology of magazine writing by the most-talented Steve Oney, who writes about athletes, writers, actors, architects, soldiers, and other men of distinction with great skill and care. We caught up with Oney this week and asked him about the kinds of men worth anthologizing.—AB

The Stacks: The stories in A Man’s World originally appeared in Playboy, GQ, The New York Times Magazine, Esquire, The Atlanta Journal & Constitution Magazine, Los Angeles, California, and Time. How much did the sensibilities—and editorial relationships—at each publication shape the tone and nature of those specific pieces?

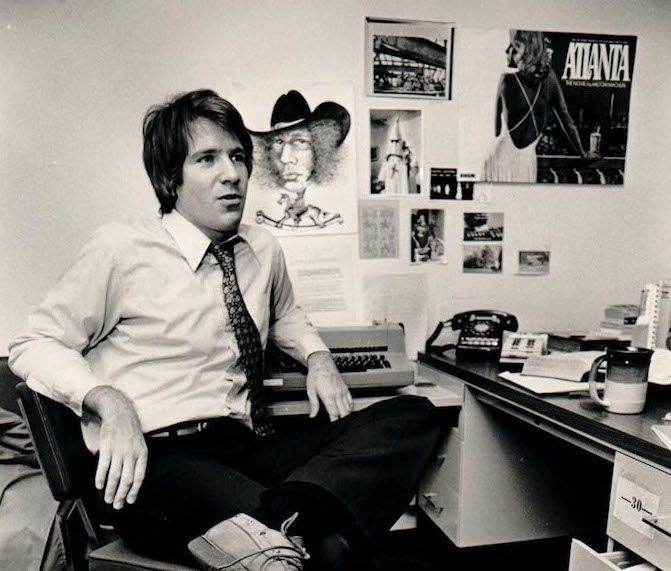

Steve Oney: I’ve generally done my best stuff when a publication is vested in my success. Early in my career I worked on staff at The Atlanta Journal & Constitution magazine. Later I was lucky enough to be on staff at Los Angeles. At both places I felt part of something in a way I never have as a freelancer. At the Journal & Constitution, I teamed up with a lot of other young writers and editors. When we were good we were very good—and when we were bad we were horrid. But we were good often enough that within a couple years Betsy Carter, at the time editorial director of Esquire, flew to Atlanta just to take us to lunch. (That’s how I ended up writing for Esquire.) It’s no accident that three of the stories in A Man’s World—“Robert Penn Warren Finds His Place to Come to,” “The Method and the Madness of Hubie Brown,” and “Getting Naked With Harry”—ran originally in the Journal & Constitution magazine. I was allotted the time to do them and paid decently for my efforts. At Los Angeles, I was lucky enough to work for an editor, Kit Rachlis, who believed in hiring staff writers then pushing them hard to meet his expectations. The result: I usually worked up to and often beyond my abilities. Five of the pieces in A Man’s World first appeared in Los Angeles, and two of those—“The Casualty of War” and “The Talented Mr. Raywood”—could not have been written any other way. Kit bought into both ideas, giving me six months to do the one about the war casualty and nine to finish the one about Raywood, a high-end con man. In other words, I was able to clear the decks and just focus on these articles—with the assurance that I’d receive a weekly check. I think the results speak for themselves. The problem with being a freelancer is that you always feel like you’re flying standby. Magazines give you a contract, but they’re really under no obligation to use your work. Not that I haven’t had great relationships with publications I freelance for. I wrote my first Playboy piece in 1986 for Steve Randall not long after he started at the magazine, and I wrote my last for him in 2012 shortly before he resigned. We had such a good rapport that we spoke to each other in shorthand. We were able to tell each other in just a few words if something was working—or not.

Q: Tell me about Harry Dean Stanton, man. How did that story come about?

SO: Not long after I saw Paris, Texas, which stars Harry Dean, I learned that it was his first role as a leading man—after 27 years in the business. I knew instantly that he’d be a great subject for a profile. The man had been waiting nearly three decades for a break. So I pitched the idea to The New York Times Magazine, and they gave me the assignment. During my research, Jack Nicholson, who’d roomed with Harry Dean back in the ’60s, told me that he is one of the “most unpredictable entities on the planet,” and that proved to be true. He’s the kind of guy who at the drop of a hat will sing Hank Williams songs. Then he’ll quote Krishnamurti and various Eastern gurus. I got great stuff about what it was like to endure a 30-year wait for stardom. I also got the thrill of picking up my phone one day and hearing a female voice say, “Hello, this is Madonna. May I speak to Steve?” She and Harry Dean are friends. Anyway, I turned in a solid piece on deadline—and the Times magazine, after telling me it was great and sending me a check, sat on it. That place has a reputation for abusing writers, and it certainly lived up to it in this instance. Finally, I begged a friend of mine at the paper—the late Martin Arnold, a wise and decent soul who at the time was supervising media coverage for the business section—to walk down to the magazine and put in a word for me. A couple weeks later my piece was in print. I guess the moral of the story is that a freelance writer must use every bit of leverage at his disposal—that, and life isn’t fair.

Q: Did you think Nick Nolte was inspired or crazy?

SO: I think Nick is both inspired and crazy. I profiled him for Premiere in 1989—that was before the DUI in Malibu, which resulted in the infamous mug shot. That photograph colors the commonly held view of Nick as dangerous and deranged. But I formed a more balanced impression. I hung out with him on the golf course, sat with him during rehearsals, watched a colorist dye his hair, and yes, saw him get drunk out of his mind at a country club bar. In each of these settings, he wore the same outfit—mismatched surgical scrubs held up by a grimy elastic back brace. So sure, that seems insane. But the more time I spent with Nick and the more I heard him talk the more respect I developed for him. He’s a true suffering artist of the sort that hasn’t really been in vogue since the Beat generation. He’s willing to put himself on the edge in search of inspiration. He’s listening for the music of the spheres and trying to trust his instincts. Does that lead to missteps? Of course it does. But his best work speaks for itself: The Prince of Tides, Who’ll Stop the Rain, and North Dallas Forty. And he keeps at it. He’s dedicated and prolific.

Q: There is also something of the tough guy/artiste in perhaps both Nolte and Stanton: Rugged and masculine yet searching, introspective, drawn to Eastern philosophies. Was there something intriguing about the combination of tough and sensitive that helped define their masculinity?

SO: Very much so. Nolte and Stanton are each poetic souls. They’re also vulnerable. That’s actually true of a lot of the guys featured in A Man’s World—although in different ways. Herschel Walker, whom I profiled for Playboy in 2011, is emotionally complicated and suffers from dissociative identity disorder. He has multiple personalities. A lot of people scoffed at that diagnosis — and still do. But I took it seriously because Herschel takes it seriously. By the way, I interviewed Herschel’s psychologist for that article. Most subjects would never let you speak to their shrink, but Herschel actually put me in touch with his.

Q: Dennis Franz comes across as very appealing. In this so-called Golden Age of TV it is hard to remember what a big deal it was to let Franz curse on the air and show his fat, white ass. But he was really an underdog for his time, wasn’t he?

SO: You’re right: Dennis Franz was a key figure, and in 1995, when I profiled him for Playboy, exposing one’s butt on TV was practically verboten—except on NYPD Blue, which was produced by Steven Bochco and David Milch and pretty much ushered in the era of realistic police procedurals we’re still in. So if a man’s naked ass can start a revolution, I guess Dennis’s did. More than that, Dennis is a superb actor. (He won three Emmys on NYPD Blue.) He played his character, Detective Andy Sipowicz, as a combination stand-up guy and renegade. Milch, who wrote most of Franz’s dialogue, used him as a mouthpiece to critique liberal culture. Sipowicz made countless outrageous cracks about the justice system, women, and politics. That was all Milch—and a harbinger of the kind of stuff he later put in the mouth of Al Swearengen, Ian McShane’s character on Deadwood.

EC: I’ve got to ask about one more piece in A Man’s World: Bo Belinksy. He was such an attractive subject for writers—Maury Allen wrote an entire book on him. And Pat Jordan’s 1971 Sports Illustrated profile was rich with period detail. He was a cult figure by the time you wrote about him. Were you aware of everything that had been written about Bo in the past? If so, how did that impact your approach to the story?

SO: The title of my profile of Bo Belinsky—“Fallen Angel”—tells you exactly what distinguishes it from Maury Allen’s fine book and Pat Jordan’s great Sports Illustrated piece. My article is about what happened after the party ended, the bills came due, and Bo could not pay because he’d lived the second part of his life as a dissolute. It was one of the hardest stories I’ve ever written, because Bo was ultimately such a self-destructive person. Just thinking about him made me ask whether I shared any of those tendencies. In 1980 I’d read Jordan’s piece—which appears in his superb book The Suitors of Spring, another classic collection of magazine articles—and I was wildly impressed and a bit starstruck. Bo comes off in that article as the coolest of cats. He’s a chick magnet. He hangs out at the Playboy mansion. He tosses off wisdom about life: “Never snow a snow man.” However, it was all a beautiful façade. The Bo I wrote about was a suicidal alcoholic and cocaine addict who after betraying his family ended up in Las Vegas working as a car salesman. The challenge for me was to chart his descent and answer the question: How did it go so wrong? As it turned out, much had been wrong from the beginning. As a young man Bo had developed a suave hustle to disguise a terror and insecurity inside. During my research, a source gave me several audio tapes Bo made near the end after he’d gained some hard-earned perspective. He talked with the most savage honesty about his missteps. Those tapes provided the guts of my article. It was like getting an interview with a dead man. Ultimately, both the glamorous version of Bo’s life portrayed by Maury Allen and Pat Jordan and the dark one I present are true, but they’re hard to reconcile. Funny, my father thought “Fallen Angel” was the best thing I ever wrote, although he could not say why. I later surmised that he saw the article as a story about the demons we all must confront. I saw it that way, too. Maybe I’m more my father’s son than I know.

[Photo Credit: via Steve Oney]