Exactly one day before I raised my right hand and marched into the Army in that blighted year of 1968, I saw the future I wanted. It was a sight that had eluded me throughout graduate school, but now, with the clock ticking down and no prayer of a military reprieve, I opened an anthology called The World of Jimmy Breslin and found the kinds of characters I wanted to write about–a first baseman who couldn’t make a doorknob work, the gravedigger who got the call when J.F.K. went down, and an arsonist whose goal was “to make the roof blow straight up into the air without bending the nails in it.”

There was also, in that wonderful collection of Breslin’s New York Herald Tribune columns, a story about a company of Marines encountering their first combat in Vietnam, walking into it as kids and coming out with their eyes turned old. Reading that chilled me to the bone, but it didn’t stop me. I was determined to devour all 292 pages on my last day of freedom, for this was an awakening. Nobody had ever told me you could do the things Breslin did in a newspaper.

Looking back, I can’t help smiling at what remains of my pre-induction infatuation. I put in 16 years on newspapers, the last 10 of them writing the sports column that was my dream until it became my burden. But that is in the past now, as is my reverence for Breslin, whose runaway imagination and general windbaggery taint him in a business that is based on getting the facts right.

Let me tell you about that book of his, though. I get as much of a charge out of reading The World of Jimmy Breslin today as I did when I was a pup. It was the first journalism anthology I ever bought, and it created in me both a habit that I have nurtured and a respect for a category of American literature that is treated like a stepchild at best.

Publishers are wary of anthologies, critics ignore them, and the reading public needs to see a big name — say, Tom Wolfe or Hunter Thomson — on the dust jacket to even consider buying them. The material is dated, the skeptics contend. Or maybe they would rather argue that such writing doesn’t match up to that found in novels and nonfiction books. And of course there is always the assumption that reading a collection of pieces that may run no more than 750 words a pop is as unsatisfying as trying to exist on three-ounce cans of water-packed tuna.

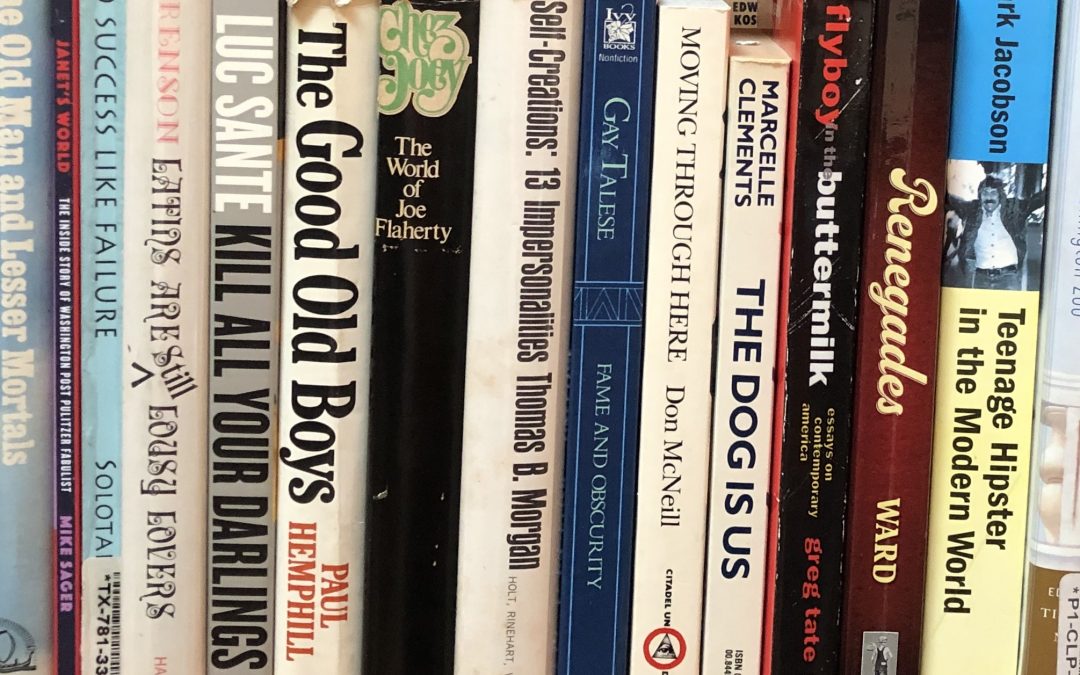

With all due respect, these naysayers are full of beans. And I have the bookcase to back me up. It sits to the right of the desk where I am writing this, and it bulges with anthologies of Red Smith’s sports-page tapestries and Joan Didion’s societal pulse-takings and A.J. Liebling’s musings on everything from the press to World War II to the Manhattan hustlers of the ‘30s who used public phone booths as their offices.

The pieces in these books and the ones that surround them were written for newspapers and magazines, which is a polite way of saying they were meant to be read and discarded. But gathering them in book form provides the chance for the prolonged life they so richly deserve.

Here, for example, is Gay Talese writing about Frank Sinatra long before Kitty Kelley ever thought to do so, writing about the moodiness and the harsh dignity and the passion that infuses his singing, and ending it with a girl in her 20s staring at him as he stops his car for a red light: “Just before the light turned green, Sinatra turned toward her, looked directly into her eyes waiting for the reaction he knew would come. It came and he smiled. She smiled and he was gone.”

You probably remember Talese for his books on the New York Times, the Mafia and sex in America, if not for his splendid anthology, Fame and Obscurity. But the majority of the writers whose collections I cherish are more obscure than famous. Some have been pushed from the spotlight by time–Joseph Mitchell, who was Liebling’s best friend and literary equal at The New Yorker; Seymour Krim, whose Views of a Nearsighted Cannoneer crystallized the spirit of the Beat Generation, and John Lardner, son of the legendary Ring and author of this classic line about a wayward prizefighter: “Stanley Ketchel was 24 years old when he was fatally shot in the back by the common-law husband of the lady who was cooking his breakfast.”

Then you have those stylists who have been deemed regional tastes, whether the region is New York (Murray Kempton, Pete Hamill), Chicago (Mike Royko) or the South and Southwest (Paul Hemphill, Marshall Frady, Larry L. King). To disregard them because of mere geography is to miss out on inspired reportage of the sort found in Gary Cartwright’s Confessions of a Washed-Up Sportswriter. Picture, if you will, this wacko Texan face to face with Candy Barr, the stripper who launched a million fantasies.

“Her blonde hair was in curlers,” Cartwright wrote. “She had scrubbed her face until it was blank and bleached as driftwood. Her green eyes collapsed like seedless grapes too long on the shelf. She wore a poor-white-trash housedress that ended just below the crotch, and no panties.”

“‘Don’t think I dressed up just for you,’ she told me.”

I don’t want to say, “only in an anthology,” but I’m tempted, because I know what a wealth of indelible lines, moments and personalities these wondrous hodgepodges can provide. In fact, I found more ammunition for my argument the other day when I dug into The Best of George Plimpton. There, tucked among the predictably charming pieces about sports and fireworks and the Paris Review crowd, was a hilarious spoof of Truman Capote battling writer’s block by adopting Hemingway’s style.

Now I can’t wait to move on to Travels With Dr. Death by Ron Rosenbaum, who strives to untangle the bizarre web that this country has woven for itself, and Mr. Personality by Mark Singer, whose approach to street scamps and power brokers can only be called Lieblingesque. All the while, however, I will wonder when some publishing house will have the brains to put out a collection of Pete Dexter’s journalism.

It is not as if Dexter doesn’t have literary clout; he won the National Book Award for his novel Paris Trout. Nor can it be that he doesn’t have the material; off the top of my head, I can think of magazine profiles of a stock-car driver gone mad and of Norman Maclean, who wrote A River Runs Through It when he was 73, as well as dozens of newspaper columns that only a wonderfully daffy tabloid like the Philadelphia Daily News would run.

But even with all that, there isn’t so much as a rumor of a Dexter anthology.* And that in itself is an indictment of the people who have the power to make such things happen. Ladies, gentlemen, whatever you are, let me put this as delicately as possible: Anthology isn’t a dirty word.

[*This was remedied in 2007 with the release of Paper Trails.]