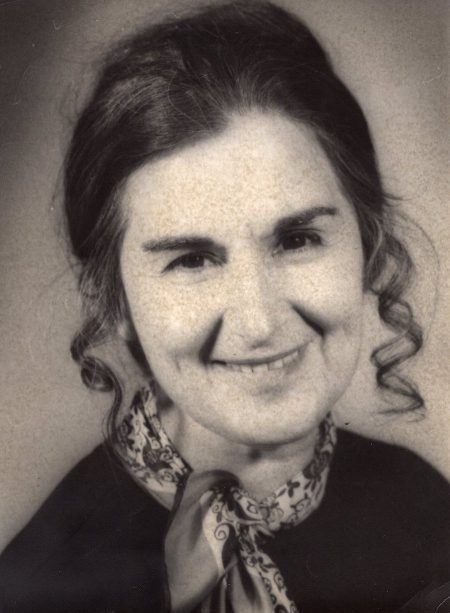

The first time I heard about Helen Dudar, I was working at Newsweek magazine as a fact-checker in the National Affairs department. A new writer named Peter Goldman had just arrived at the magazine from St. Louis, and he was good. He was really good. Everyone was buzzing around about how good, how really good, Peter Goldman was, and someone finally buzzed it right at Peter Goldman himself, who replied—at least this is how I remember it—that he just wished he could write as well as his wife.

I had no idea who his wife was, but I soon found out. He was Helen Dudar of the New York Post. And she was, according to my friend Nan, brilliant. Nan had a way of saying the world brilliant that was completely terrifying, and I believed virtually everything she ever said to me for quite a long time. From Nan I learned not just about Helen but also about Brie and vitello tonnato and the omelet place, and she was right about Helen and Brie although not really about vitello tonnato or the omelet place. Anyway, I began to read Helen Dudar in the New York Post, and she was as good as I’d been told.

And then, within a few weeks, I was there, too—a reporter on tryout at the paper, and met the now legendary-to-me Tiny Helen, as Peter called her, and got to watch her do her thing. And she could do anything. She could write a lyrical feature piece, she could write hard news, and she was—in a city room full of world-class rewritemen—the greatest rewriteman of all. I can see her at the rewrite desk in the center of the newsroom on November 22, 1963, as page after page of wire copy mounted up, reporters phoned in from the street, and she sat at the typewriter, with a phone set on her head, writing the lead piece on the Kennedy assassination. Flawlessly. Calmly. One paragraph at a time of clean, clear prose.

She was grace under pressure, she was the epitome of unselfconscious professionalism, she was simply great. I idolized her, and then, as I got know her, I found more and more things to admire. My eventually theory about her was that Helen wrote the way Ella Fitzgerald sang. They both made it look easy when it wasn’t. They both avoided anything extraneous, or self-serving, or self-aggrandizing, or forced, or strained; what Helen and Ella both managed to bring off was the equivalent of the purest, clearest spring water. For years, I tried to figure out how she did it—at the Post and later, when she became a wonderful magazine writer—but eventually I gave up and simply enjoyed it all.

I was also, happily, the beneficiary of her wisdom on a great many subjects. Unlike Nan, Helen was right about everything: fish soup with rouille, exercise as an antidote to depression, copper pots, the Bridge company, Sonia Rykiel, Fairway, and the South of France, to name just a few of the things I know something about because of her.

She is a writer’s writer, a journalist’s journalist, a reporter’s reporter. She’s a generalist in the most flattering sense of the word—there’s no subject she can’t write about with intelligence. Well, not mere intelligence—a “demanding, sinewy intelligence,” to quote one of Helen’s more felicitous phrases, which happens to be quoted in Webster’s Dictionary, no less. After she left the Post, she became at ease writing about Cezanne, Arthur Miller, Jack Nicholson and Rome. “Helen Dudar frequently writes about the theater,” it would say at the bottom of her articles. Or: “Helen Dudar frequently writes about art.” Or: “Helen Dudar frequently writes about publishing.” The truth is that Helen Dudar frequently writes about everything, and does it better than just about anyone else.

How’s that for an introduction?

While you are it is, dive into this sampler of Dudar’s work: portraits of acting legends Uta Hagen, Lauren Bacall, Shelley Winters, and James Earl Jones; and writing legends, Toni Morrison and Patricia Wells. Also, dig into smart essays on J.D. Salinger, and the seductions of MTV.—AB.

[This essay is featured here with permission from Nora Ephron’s Estate.]